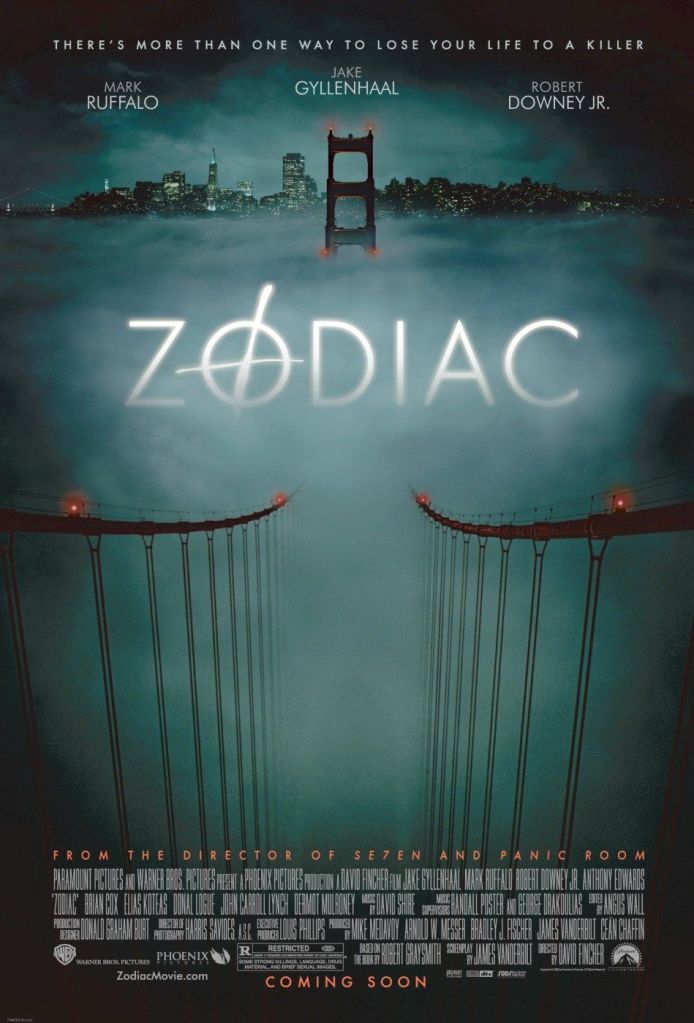

A chilling chronicle of the hunt for a serial killer told with a superb mix of journalism and filmic flair

Director: David Fincher

Cast: Jake Gyllenhaal (Robert Graysmith), Mark Ruffalo (Inspector Dave Toschi), Robert Downey Jnr (Paul Avery), Anthony Edwards (Inspector Bill Armstrong), Brian Cox (Melvin Belli), Elias Koteas (Sergeant Jack Mulanax), Donal Logue (Captain Ken Narlow), John Carroll Lynch (Arthur Leigh Allen), Dermot Mulroney (Captain Marty Lee), Chloë Sevingy (Melanie Graysmith), John Terry (Charles Thieriot), Philip Baker Hall (Sherwood Morrill), Zach Grenier (Mel Nicolai)

It’s one of the great unsolved mysteries of American history, like San Francisco’s version of Jack the Ripper. For a large chunk of the late 60s and early 70s, a serial killer known only as “the Zodiac killer” murdered at least five (and claimed 37) innocent people, all while sending mysterious, cipher-filled letters to San Francisco newspapers, taunting police and journalists for failing to catch him and threatening further violent acts. The investigation sifted through mountains of tips and half clues but only produced one possible suspect, Arthur Leigh Allen: though no fingerprint or handwriting match could conclude a case.

The story of the hunt for this elusive killer, stretching into the 1980s and concluding with another dead-end coda in 1992, is bought to the screen in a film from David Fincher that expertly mixes cinematic flair with journalistic observation. Channelling All the President’s Men and 70s conspiracy thrillers as much as it does the dark obsession of Fincher’s Seven, Zodiac is a master-class not only in the bewildering detail of large-scale investigations (in the days before computer records and DNA evidence) but also the grinding, destructive qualities of obsession, as those hunting the Zodiac killer struggle to escape the shadow of a case that grows to dominate their lives.

Zodiac focuses on three men, all of whom find their lives irretrievably damaged by their investigation. At first, it seems the drive will come from Robert Downey Jnr’s Paul Avery. Avery is the hard-drinking, charismatic, old-school crime correspondent on the San Francisco Chronicle. In a performance exactly the right-side of flamboyant narcissism, Downey Jnr’s Avery is a man who likes to appear like he takes nothing seriously, even while the burden of the case (and a threat to his life from the Zodiac killer) tips him even further into a drink habit that is going to leave him living in a derelict houseboat, in a permanent state of vodka-induced intoxication.

The second is Inspector Dave Tosci, a performance of dogged, focused professionalism from Mark Ruffalo. He’s confident he’ll find his man, and will go to any lengths to do it, staying on call night and day, and hoarding facts about the case like a miser. He relies more than he knows on level-headed, decent partner Bill Armstrong (played with real warmth by Anthony Edwards). Tosci’s self-image and belief slowly crumble as every lead turns dead end, every gut instinct refuses to be backed by the evidence. The killing spree becomes his personal responsibility, a cross he bears alone for so long that when a belated letter from Zodiac surfaces in 1978, his own superiors believe Tosci sent it in some vain attempt to keep a cooling case alive.

Our third protagonist, present from the arrival of the very first Zodiac letter at the door of the Chronicle, is Jake Gyllenhaal’s Robert Graysmith. A quiet, studious, teetotal political cartoonist who is literally a boy scout, Graysmith spent a huge chunk of the 70s and 80s trying to crack the case, eventually turning his investigation into a best-selling book. It’s Graysmith who becomes the focus of Fincher’s investigation of obsession. The glow of monomania is in Gyllenhaal’s eyes from the very start, as the cipher and its deadly message spark a mix of curiosity and moral duty in him. He feels compelled to solve the crime, but it’s a compulsion that will overwhelm his life. The Zodiac is his Moby Dick, the all-powerful monster he must slay to save the city. (“Bobby, you almost look disappointed” Avery tells him, when Avery suggests some of the Zodiac’s murderous claims are false, as if reducing the wickedness of the Zodiac also reduces the power of Graysmith’s quest.)

The real Graysmith commented when he saw the film, “I understand why my wife left me”. It’s a superb performance of school-boy doggedness, mixed with quietly fanatical, all-consuming obsession from Gyllenhaal, as the film makes clear how close he came (closer than almost anyone else) to cracking the case, but nearly at the cost of his own sanity. Graysmith pop quizzes his pre-teen children on the case over their breakfast (a far cry from, at first, his instinct to shield his son from the press coverage) and as he becomes increasingly unkempt, so his house more and more becomes a mountain of boxes and case notes.

It’s the secondary theme of Zodiac: how obsession doesn’t dim, even when events and evidence drop off. The second half of the film features very little new in the case (which peaked in the early 70s) but focuses on the lingering impact of the ever more desperate and lonely attempts to solve it. Armstrong, the most well-adjusted of the characters, perhaps knew it was a hopeless crusade when he threw his cards in and left the table after a few years to spend time with his children while they grew up. Avery cashes out as well – even if his health never recovers. Tosci is cashiered from the game, and even Graysmith finally realises the impact on him.

That second half of the film is long. Too long. It also, naturally, leaves us with no ending – a sad coda that hints at the guilt of primary (only) suspect Arthur Leigh Allen, but gives us (just like the surviving victims) no closure. It’s fitting, and deliberate, but still the only real flaw of Zodiac is that, at 150 minutes, it’s too long. The deliberate draining of life from the case, like a deflating balloon, also impacts the narrative, which consciously drops in intensity (and, to a degree, interest – despite Gyllenhaal’s subtle and complex work as Graysmith). It’s even more noticeable considering the compelling flair with which Fincher delivers the first half of his scrupulously researched film.

Fincher and screenwriter James Vanderbilt spent almost 18 months interviewing everyone involved with the case. Nothing was included in the film unless it could be verified by witnesses. That included the crimes of the Zodiac: only attacks where there were survivors are shown, the only minor exception being Zodiac’s murder of a taxi driver (where only distant eye-witnesses were available) – even then, every event is confirmed by ballistics and no dialogue is placed into the mouth of the victim. The film also acknowledges the unknown nature of the Zodiac killer: each time the masked killer appears in recreations of his crime he is played by a different (masked) actor, subtle differences in build, tone of voice and manner reflecting the contradictory eye-witness statements. These chilling scenes are shot with a sensitivity that sits alongside their horrifying brutality. Fincher felt a genuine responsibility to reflect the horror of what happened, but with no sensationalism.

Instead, he keeps his virtuoso brilliance for the investigation. The newspaper room filling with the super-imposed scrawl of the Zodiac killer, while the actors read out the words. Restrained but hypnotic editing, carefully grimed photography, camera angles that present everyday items in alarming new ways, a mounting sense of grim tension at several moments that makes the film hard to watch. A superb sequence surrounding the Zodiac’s demand to speak to celebrity lawyer Melvin Belli (a gorgeous cameo from Brian Cox), first on a live TV call-in show, then in person (a “secret meeting” swamped by armed police, which Zodiac, of course, doesn’t turn up to). This is direction – aided by masterful photography (Harris Savides) and editing (Angus Wall) – that immerses us in a world (like drowning in a non-fiction bestseller), while never letting its flair draw attention to itself.

Zodiac was a box-office disappointment and roundly forgotten in 2007. It’s too long and loses energy, but that’s bizarrely the point. It implies, heavily, that Allen (played with a smug blankness by John Carroll Lynch) was indeed the killer, but doesn’t stack the deck – every single piece of counter evidence is exhaustingly shown. In fact, that’s what the film is: exhaustive in every sense. It leaves you reeling and tired. It might well have worked better, in many ways, as a mini-series. But it’s still a masterclass from Fincher and one of the most honest, studiously researched and respectful true-life crime dramas ever made. And just like life, it offers neither easy answers, obvious heroes or clean-cut resolutions, only doubts and lingering regrets.