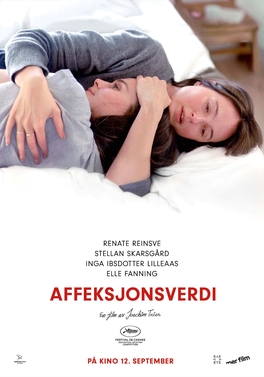

A autuer director tries to bond with his daughters in this heartfelt drama of family dynamics

Director: Joachim Trier

Cast: Renate Reinsve (Nora Borg), Stellan Skarsgård (Gustav Borg), Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas (Agnes Borg Pettersen), Elle Fanning (Rachel Kemp), Anders Danielsen Lie (Jakob), Jesper Christensen (Michael), Lena Endre (Ingrid Berger), Cory Michael Smith (Sam), Catherine Cohen (Nicky), Andreas Stoltenberg Granerud (Even Pettersen), Øyvind Hesjedal Loven (Erik), Lars Väringer (Peter)

Famed auteur director Gustav Borg (Stellan Skarsgård) has seen his career quietly stall in the past fifteen years. He frequently failed as a father to his two daughters, Nora (Renate Reinsve) now a leading classical actor and Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas) a married academic researcher with her own son, who she and Nora give a care and attention they never received from Gustav. However, Gustav has an olive branch for Nora – a semi-autobiographical film about his mother that he wrote for Nora. When she rejects him, he secures funding with Hollywood star Rachel Kemp (Elle Fanning) and remains a presence in their lives as he plans to shoot the film in their family home.

Trier’s compelling portrait of a family confronting their feelings, explores the bonds that tie families together and if they go deeper than just sentiment. Superbly directed, it masterfully explores the confused, awkward tensions between children and their father and is blessed with three superb performances from Reinsve, Lilleaas and Skarsgård that genuinely feel like a family unit. With a naturalness in their comfort with each other, all three give a master class in micro-reactions (and aggressions) that show the raw nerves a father can touch with his clumsy attempts to connect with his daughters.

The connection between Reinsve and Lilleaas is so intensely moving, it’s hard not to believe they aren’t sisters. These two extraordinary actors share scenes of sisterly love that are heartfelt in their simplicity. Just as their pained, struggling to hold back tears when expressing their feelings carries a huge impact. Beneath all the snapped words, both daughters have a genuine need to love and be loved by their father, someone they clearly don’t always like but who they also need – and, in a strange way, understand.

Reinsve (absolutely brilliant) shows Nora hiding her emotions but collapsing into herself when distraught. She’s reduced to shocked hostility when re-encountering her father, who she blames for her struggle to form emotional bonds with others. Reinsve is compelling as this fragile, empathetic person who has buttoned herself into a protective shell: she has a beautiful moment after opening her heart to a fellow married actor she is having an affair with, only for her to recoil with pain when he politely rejects her. Nora invests so much of her feelings in her acting, that it leaves her with crippling stage-fight before performances (a brilliantly staged scene sees her demand to be practically man-handled on stage mid-stage fright, which anyone whose acted can sympathise with). The more we learn about her pained background, the more Reinsve invests this character with a deeply affecting sadness just under the surface, making us more and more aware of her vulnerability.

She’s equally matched by Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas as Agnes, who feels she must provide the emotional glue to hold this strange family together. She has built the warm, protective home for her family which the others are drawn to (both Nora and Gustav are devoted to her young son Erik), but Lilleaas shows Agne has worked to re-channel her feelings. Having once played the child-lead in one of Borg’s films, she painfully tells him it was the best summer of her life as it was the only one where she had her father’s full attention. It’s a generous, subtle and deeply affecting performance, of emotional bravery as we discover the depths of her love and loyalty to her sister.

Skarsgård, meanwhile, gives one of the finest performances of his career as the egotistical but regretful Borg, whose pain at his growing artistic and familial irrelevance is clear. He’s full of charm and warmth, but also ruthlessness: he forms close bonds with those he’s working with, but moves on the second the project completes. It’s an attitude he has extended to his family, which he wishes to change, but lacks the emotional intelligence to do so, as the charm he uses for the festival circuit fails to land with his family. He’s a man who can only express his true feelings in the language of film, through art rather than his own words. It’s a superb performance.

Sentimental Value is frequently shrewd and funny about filmmaking. Borg is facing the dying of the light, making his film for Netflix and looking intensely pained when its suggested it may never be screened in a cinema. There is a brilliant joke where he gifts Erik a hideously inappropriate collection of DVDs (including The Piano Teacher and Irreversible) made even funny when Agnes says they don’t even own a DVD player. If there is one way Borg does differ from Bergman (his clear inspiration), it’s his boredom with theatre: he has never seen Nora act, clumsily assumes she is playing Orphelia in her next show (she’s actually playing Hamlet) and tells her (one of Norway’s leading stage actors) that appearing in his film could be ‘a big break’.

But in the film world, Borg is clearly a master: calm, patient and able to inspire with enthralling descriptions of proposed shots, able to tease out beautiful work from actors. No wonder Rachel Kemp wants to work with him. Elle Fanning is excellent in a nuanced, intelligent performance as a gifted Hollywood starlet who begins to instinctively feel she is wrong for the lead in a European auteur-epic blatantly written for someone else. Fanning has an extraordinary scene, where she gives a reading of a key monologue from Borg’s film: her talent is immediately clear, but her skilled emotional reading is also completely out-of-tune for the mannered, imagery-dense text. Fanning makes this character empathetic, respectful, earnest and a true artiste, Trier inverting our expectations of any pop at Hollywood self-obsession.

A beautifully played chamber piece, it’s not just the Bergman-inspired career of Borg (his proposed film is pure Bergman stylistic homage) that makes Sentimental Value feel like it has a little touch of the master. Trier brings his camera to focus intensely on his actors, to let their emotions fill the screen and play in front of us. He even indulges a Persona style flourish where their three faces merge and combine with each other, under-lining the essential bonds that tie them together.

In a classic Bergman-style metaphor, the film is framed around ancestral family-home which literally has a flaw crack running through it. The film opens with Nora recounting a school essay she wrote imagining her house responding to events filling it – a mix of her childhood play and ferocious parental arguments. Sentimental Value subtly layers in roots of adopted trauma, with memories of Gustav’s mother (an imprisoned and tortured resistance fighter) who committed suicide when he was a young boy, which deepen the emotional complexities and fraught baggage every character carries.

What’s also beautiful about Sentimental Value is that it always feels true. There are not artificial moments of actorly grand-standing leading to emotional breakthroughs, but quiet (and even more moving) moments of genuine truth and honesty. Trier isn’t afraid to make the film funny, but also brilliantly shows that there is a lot more than just sentiment drawing families together, with a revelation that while Borg may never be able to express it the way his daughters want, he understands and loves them in ways no-one else can. It’s a beautiful, masterfully made, deeply thought-provoking and emotionally mature work that continues to mark Trier (and his actors) as major talents.