Hollywood and the revolution meet in von Sternberg’s sympathetic look at White Russians

Director: Josef von Sternberg

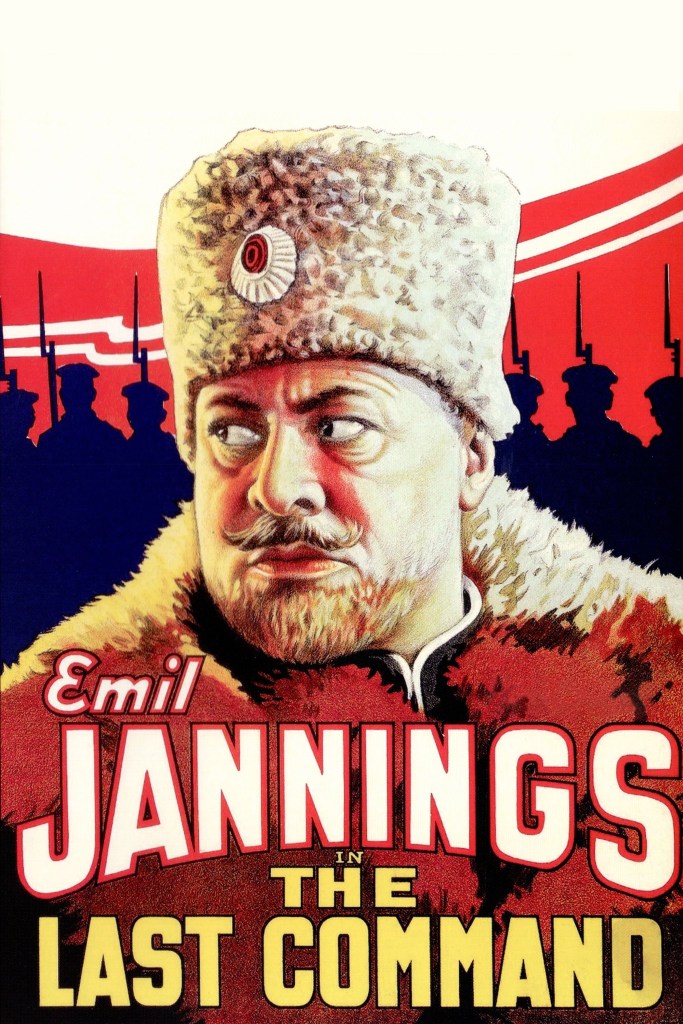

Cast: Emil Jannings (Grand Duke Sergius Alexander), Evelyn Brent (Natalie Dabrova), William Powell (Lev Andreyev), Jack Raymond (Assistant director), Nicholas Soussanin (Adjutant), Michael Visaroff (Serge)

Hollywood director Lev Andreyev (William Powell) flicks through photos of extras, searching for someone to play the Russian General in his WW1 epic. His eyes light up – the perfect face! Sergius Alexander (Emil Jannings) is summoned. But Andreyev has ulterior motives: Sergius Alexander is a former Grand Duke who clashed with the revolutionary Andreyev in Russia ten years ago and this is the chance for revenge Andreyev has longed for. A cousin of the Tsar, Sergius Alexander was commander of the Western Front. Imperious but noble, deeply patriotic, he gave everything for Russia, despite falling in love with revolutionary Natalie Dabrov (Evelyn Brent). The revolution turned Sergius into a traumatised shell and kitting him out in uniform again impacts his sanity.

Von Sternberg’s The Last Command is two films mixed into one. It’s partly a satire on Hollywood, a machine specialising in creating artificiality that chews extras up and spits them out with little regard for their well-being (rather like the trench system the film is set in). The other – and more dominant – part is a classic melodrama of a noble Russian lost and powerless as his world collapses around him. It’s this second part that dominates the film, almost an hour of its ninety-minute run-time being taken up with its Russian flashback sequence. Like many von Sternberg films it’s charged with a mix of sex and sadomasochism, while also being a sympathetic, white-Russian look at the revolution.

Emil Jannings received the first ever Best Actor Oscar for this (and the now lost The Way of all Flesh). At the time Jannings was seen as one-of (if not the) greatest actor in the world, based on his mastery of the expressive arts of silent cinema. Janning’s physicality, his emotion-filled piercing gaze is duly showcased. Jannings effectively plays two parts: the Sergius Alexander of the Russian era, the Russian aristocrat who emerges as a man of honour, dignity and patriotism; and the Sergius Alexander of the present day, a timid, broken man, forever twitching, scared to look people in the eye. In both cases, von Sternberg’s camera constantly pulls back to Jannings whose ability to transform and twist his body – from ram-rod officer to broken husk – is executed perfectly.

Von Sternberg’s gives the bulk of the film’s run-time over to the build-up of the Russian revolution. While The Last Command gives some criticism to the ancién regime – our first shot is of a poverty-stricken mother and baby sitting in the snow, while the Tsar is a paper king more interested in parades than reality – von Sternberg’s affection is clearly for the decent nobles trying to make the system work. The revolutionaries are largely violent or shadowy manipulators (we get a brief scene with obvious Lenin and Trotsky stand-ins, presented as hypocritical middle-class looking schemers focused on power). On the contrary Sergius Alexander is interested only in the good of Russia.

It’s that which wins him the unexpected respect of feared revolutionary Natalie Dabrova, well played by Evelyn Brent. Dabrova is a power-keg whose fire and passion seizes the fascination of Sergius. Their initial meeting is the only time von Sternberg presents him as a tyrannical figure, sitting in an office questioning potential revolutionaries for his own amusement (including a whip across the face for Andreyev). But from there Sergius’ essential decency emerges – his politeness, his old-school chivalry. He treats her like a lady and (eventually) courts her with a Victorian gentility.

That contributes to Natalie’s shift towards seeing Sergius as a man trying his best in difficult circumstances rather than the ogre she assumed. Von Sternberg masterfully shoots the pomp and pageantry of the old Russia, full of military parades, fine dining and smart uniforms using this pageantry to show how it disguised the real threat facing the country. There are also elements of the sado-masochistic in the relationship between Natalie and Sergius. This bastion of the system is attracted to this woman who wants to burn the whole thing down. Visiting her in her bedroom, spotting a hidden pistol, is there an air of debased excitement when he turns his back on her and all but invites her to shoot him? In turn, Brent is almost a prototype of the classic Dietrich character, a strong, imperious woman, who dominates men, torn between conflicting desires.

There is a neat series of contrasts and contradictions in all the characters in The Last Command. Sergius is both a Tsarist bully, a decent man interested only in his country and a shattered husk in Hollywood. Lev is a firebrand revolutionary and an aristocratic Hollywood director. Natalie is a fascinating mix: a banner-waving anarchist who fits neatly into Sergius’ cocktail parties, who despises and loves the General. Duality and hidden identities hints at hidden desires within all the characters in a world tearing itself apart.

That collapse of order is the stunning heart of von Sternberg’s film. The seizure of Sergius’ train by revolutionaries, the final act before his exile, is superb in its vibrant tracking shots and Eisenstein-inspired energy. Jannings is placed at the heart of the crowd in a series of tracking-shot marches through baying crowds all pulling, spitting, pushing and abusing him that is part walk to calvary, part fantasy of humiliation. There are moments of understanding for the masses – a scene shows Tsarist soldiers machine-gun down a mob – though it’s balanced by the ruthless shooting they carry out on wounded soldiers. Sergius is reduced to the lowest-of-the-low, a humiliated figure shovelling coal for his revolutionary masters while they conduct (what looks like) an orgy in his state compartment.

Humiliation is also the name of the game in Hollywood. While The Last Command is more about its sympathetic look at good White Russians let down by the system (fitting von Sternberg’s imperialist sympathies), it throws in to its first and final act an uncomfortable look at Hollywood. Extras crowd at the studio door as another sea of desperate humanity (Sergius’ buffeting here in this crowd, must remind him of that humiliating walk through the mob in Russia). Costumes are flung at people identified only by tickets. Assistant directors treat people like dirt and extras are seen only as props.

But the satire is blunted by the fact that the treatment on set is motived by personal animosity. After all this is Lev – William Powell, rather good and clearly channelling von Sternberg – living out his own revenge fantasy. A sharper satire would have had no link between director and extra, merely seen the heartless system exploit a past trauma for its own benefit – with terrible consequences.

The Last Command is less a satire on Hollywood and more a rose-tinted look at the decent figures in the Tsarist system, with touches of satire on revolutionaries who are either power-mad middle-classes or working-class simpletons seduced by the temptations of drink and sex. It’s also a subtle smuggling in of the director’s own sexual fascinations, with Jannings a superb vehicle for this fantasy of humiliation with Brent shot with the sultry imperiousness of a potential dominatrix. For all this it’s a fine film, a visual marvel and a fascinating character study.