|

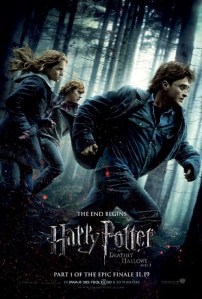

Harry and Voldemort prepare for their final showdown in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2

|

Director: David Yates

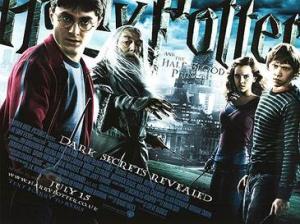

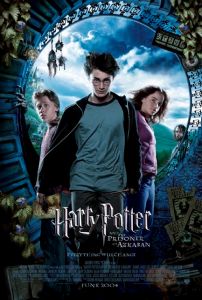

Cast: Daniel Radcliffe (Harry Potter), Rupert Grint (Ron Weasley), Emma Watson (Hermione Grainger), Helena Bonham Carter (Bellatrix Lestrange), Jim Broadbent (Professor Slughorn), Robbie Coltrane (Hagrid), Ralph Fiennes (Lord Voldemort), Michael Gambon (Albus Dumbledore), John Hurt (Ollivander), Jason Isaacs (Lucius Malfoy), Gary Oldman (Sirius Black), Alan Rickman (Severus Snape), Maggie Smith (Professor McGonagall), David Thewlis (Remus Lupin), Emma Thompson (Professor Trelawney), Julie Walters (Molly Weasley), Mark Williams (Arthur Weasley), David Bradley (Argus Filch), Ciarán Hinds (Aberforth Dumbledore), George Harris (Kingsley Shacklebolt), Gemma Jones (Madam Pomfrey), Kelly MacDonald (Rowena Ravenclaw), Helen McCrory (Narcissa Malfoy), Miriam Margolyes (Professor Sprout), Geraldine Somerville (Lily Potter), Adrian Rawlins (James Potter), Warwick Davis (Griphook/Professor Flitwick), Matthew Lewis (Neville Longbottom), Evanna Lynch (Luna Lovegood), Bonnie Wright (Ginny Weasley), James Phelps (Fred Weasley), Oliver Phelps (George Weasley), Domhnall Gleeson (Bill Weasley), Clémence Poésy (Fleur Delacour), Guy Henry (Pius Thicknesse), Nick Moran (Scabior), Natalie Tena (Tonks)

And so here we are. After 19 hours and 40 minutes, the Harry Potter franchise draws to a close in the rubble of Hogwarts. The franchise goes out swinging for some big hits – and it misses some of them – but at least it’s trying. If this turns out to be one of the least satisfying films in the franchise (at best the 6th best Harry Potter film), it’s not because they haven’t thrown anything at it.

The film adapts just under the last half of JK Rowling’s final novel. In an interesting structural twist, it actually ends up covering just over one day of time: between our heroes breaking into Gringotts Bank and the final confrontation between Harry and Voldemort, less than 24 hours has taken place. Nothing is really made of this in the film, but it’s an interesting thought. In fact Yates’ film is full of interesting half-thoughts that never go anywhere. More than any other film in the series, this is one where it is essential you’ve read the book before viewing it. Without the book you don’t get any of the rich context for most of the events.

This all culminates, for me, in the way the film falls apart in the last 20 minutes or so. This final section of the film changes, or cuts, so much of the book’s thematic depth, so many of its plot strands and explanations, that every time I see it I feel my disappointment starting to rise. I don’t want to be the guy who says “just shoot the book” – but if any film could have stuck with the book it’s this one. Why did they cut and change so much of this stuff? Did they really think, after almost 11 years and 20 hours of screen time, we wouldn’t have the patience for some of the more complex things from the book? Did they really feel that they had to stamp their own distinctive vision on it? Anyway, here are the things that always annoy me about this film:

1. Dumbledore’s backstory gets forgotten

Okay this is a minor one – and the film does leave some hints in. But for GOODNESS’ SAKE, they cut this book into two films, spent ages in the first film talking about the mysteries of Dumbledore’s dark past, then just as we meet Dumbledore’s brother Aberforth (a neat turn from Ciarán Hinds) and are about to get an explanation, Harry basically says words to the effect of “I’m not worrying about that. And neither should you folks. On with the film”.

Okay this is a minor one – and the film does leave some hints in. But for GOODNESS’ SAKE, they cut this book into two films, spent ages in the first film talking about the mysteries of Dumbledore’s dark past, then just as we meet Dumbledore’s brother Aberforth (a neat turn from Ciarán Hinds) and are about to get an explanation, Harry basically says words to the effect of “I’m not worrying about that. And neither should you folks. On with the film”.

Even the Ghost of Dumbledore doesn’t get to explain any of this stuff. All the careful mood build of Part 1 is just thrown away. The book is about learning about death, the futility of the search for power, and humility. Dumbledore’s backstory of failed ambition is a massive part of this – and it gets dropped. It’s not like we didn’t have time in a series that has churned out films pushing up to three hours in length. I mean why put all that stuff in the first film, if you aren’t even going to reference it at all in the second film?

2. The Deathly Hallows get benched

Again wouldn’t be quite so bad if we hadn’t spent a huge amount of time in the first film talking about them – but are the words Deathly Hallows even mentioned here? Instead, just like Voldemort, the film is seduced by the elder wand, focusing everything on the ownership of this MacGuffin. The point of the book is that all this stuff is a chimera –and that the real point is learning that death should not be feared but accepted at the proper time.

As it is, this never gets built on – and the importance of the resurrection stone (including why it tempted Dumbledore so much) never gets explained. Rather it just comes down to who controls the powerful thing, with none of Rowling’s richer themes.

Harry ends up controlling all three here but we never really get the sense of Harry controlling them all, or understand his decision to throw away the stone, or his realisation that death is not to be feared but accepted.

3. Neville gets blown away

Gotta feel sorry for Matthew Lewis (who is very good here). Reading the book he must have been thrilled: “So I pull the sword out of the sorting hat and then in one move cut the head off the snake like a total bad ass”. This should have been a great moment (it’s an iconic one from the book). Instead Neville gets blasted and, presumably to give them something to do, Ron and Hermione spend ages trying to kill the snake (intercut with Harry and Voldemort fighting) until finally Neville gets to lop that head off – by which point the moment has well and truly passed.

4. No one mentions Voldemort keeps making the same mistakes

In the book, Harry has a beautiful moment where he basically tells our Tom that he’s made the same mistakes over and over again. Namely that, by killing Harry, who sacrificed himself for love, he made exactly the same mistake as he did with Harry’s mother and now cannot harm any of those Harry died for (i.e. the rest of the cast). It’s a great moment, where finally Harry understands what the novels have been building towards. Doesn’t merit a mention.

In the book, Harry has a beautiful moment where he basically tells our Tom that he’s made the same mistakes over and over again. Namely that, by killing Harry, who sacrificed himself for love, he made exactly the same mistake as he did with Harry’s mother and now cannot harm any of those Harry died for (i.e. the rest of the cast). It’s a great moment, where finally Harry understands what the novels have been building towards. Doesn’t merit a mention.

Neither does Voldemort’s childish obsession with famous things – he is consumed with belief in the power of a wand, he can’t let go of associating his horcruxes with famous things and the lineage of iconic wizards, etc. etc. Voldemort is basically a big, silly, empathy-free, sulky teenager – the film misses this point entirely.

Instead of explanations and depth, the film reduces Harry and Voldemort’s final clashes into dull punchy-bashy stuff. The director clearly fell in love with the visual idea of Harry and Voldemort’s heads merging together while apparating. This is a visual image that I hate because it (a) feels like showing off and (b) would only work if they were semi-reflections of each other – which they certainly aren’t. They are polar opposites. It’s a flashy effect that actually makes no thematic sense what-so-bloody-ever.

5. Voldemort goes out like a 3D special effect

Perhaps not a surprise in a film, but Voldemort gets killed and disintegrates into a huge puff of 3D-film smoke. I hate this. I hate it. I really, really, really hate it. I’ll tell you why:

- The spells used in the duel are really unclear – it’s a great moment in the book that Voldemort’s killing curse rebounds against Harry’s disarming curse – instead we get the bright lights.

- Voldemort dreads death more than anything – and Rowling’s writing of his body falling dead to the ground like any other normal dead guy taps exactly into what Voldemort spent his whole life struggling against. It’s a beautiful irony.

- No one knew if Voldemort was dead or not the first time because he disappeared. In the book he is killed, by his own curse, in front of everyone and his body is left behind for everyone to look at and say “yup. Guy is dead”. Not here. Here he blows up in a puff of smoke in front of no witnesses. Did Harry just head back into the great hall and say “Okay guys. Take my word for it. He’s dead. He just is. Trust me on this. It’s not like last time. Totally dead. Promise.”

Wow. Okay that’s not really a review is it? That’s just like a disappointed fan whining “I don’t like it because it is different”. But my point isn’t that this is bad because it’s different. It’s bad because it takes stuff from the original and changes it AND NOT FOR THE BETTER. Moments that worked beautifully, or carried so much weight in the original are bastardised crudely for no clear reason.

As I say, after almost 18 hours and a life time (for many viewers) of growing up with these characters: surely we could have given the film a bit more time and allowed some actual intelligent context from the books to creep in? Surely we had the patience for Harry getting to point out to Voldemort how wrong he is? Everyone in the audience was ready for that right? If there was one film people were probably willing to dedicate three hours of their life too, in order to see it done properly it was this one, right? Rather than rushed by in a little over two?

But no this film goes always, always, always for the big spectacle. Not that this always work: Yates doesn’t shoot the battle hugely well. Aside from one excellent sequence which shows our three heroes trying to get across the castle courtyard, while chaos rages around them (beautifully scored as well), the battle is unclear, dingy and not hugely exciting. Again, I’d have liked to have had a bit more of this – to get some moments with this huge cast doing stuff in the battle (especially since they are ALL back – kudos to the producers there).

It’s a real, real shame because honestly parts of this movie are really, really, really good. Tom Felton is cracking again as Draco – and the film gives real development time to showing the impact all this has on the Malfoy family with genuine empathy. The break-in at Gringotts is exciting and fun – as well as giving Warwick Davies his best moment in the series as two-faced Griphook. Inventions and flourishes, such as Harry having visions of an enraged Voldemort slaughtering the staff of Gringotts in fury, are chilling.

Some moments of the book are carried across really well, in particular Snape’s escape – a powerfully filmed sequence of bravery from the pupils, and some great work from Maggie Smith. Yates really understands how to get moments of magic to work: the creation of the shield around Hogwarts is totally spine-tingling. When the film sits and breathes it generally gets it right. Fiennes is terrific still as Voldemort, serpentine, arrogant, unsettling. He gets some lovely moments here – from fury, to pained fear (as horcruxes bite the dust) to an almost-funny-awkward-mateyness as he tries to seduce Hogwarts pupils to his side (his awkward hug of Draco is terrific).

The three leads are of course great. Daniel Radcliffe could certainly have delivered the more complex moments of the book if he had been given the chance. He even does his best to sell the slightly awkward coda “19 years later”: a controversial sequence, it makes a great footnote in the book but it was always going to be a tough ask to make three teenagers look like 40 year olds convincingly, particularly when we are nearly as familiar with their faces as our own.

There are some troubling and failed moments in this film, stuff that doesn’t work. But then there is this:

Oh wow. For all that the film changes stuff from the books for the worst – this is a moment it unquestionably does better. And a massive, massive part of this has to be down to Alan Rickman. Rickman was told this backstory from the start of the films – and he delivers it with a passionate commitment here. Helped by brilliant score, and fascinating re-editing of moments from previous films seen from new angles, Rickman delivers the reveal of Snape’s heartbreaking moments perfectly.

Was I tired? Was it the added impact of Rickman’s own depth? I don’t know but I shed tears watching this again. It’s just a beautiful, beautiful, beautiful piece of film making. Everything in it works perfectly: directing, writing, music, editing, filming and above all the acting. It’s just sublime. For all the film misses the point elsewhere it finally totally gets it here. I would take this moment over dozens of moments of Harry and Voldemort fighting each other.

And yes this Harry Potter film might miss the point, and it might bungle the ending, and it might well fail to carry across the richness and intricate plot explanations of Rowling’s original. Yes it gets bogged down in “who controls this wand” and yes it misses the point completely about the film being about learning to overcome a fear of death and defeat (something Voldemort totally fails to do) but then it has moments where it works wonderfully like this.

But in these films we got a beautiful franchise, with some excellent films. It’s always going to reward constant viewing. And it will always move the viewer. And it’s always going to be great.

Always.