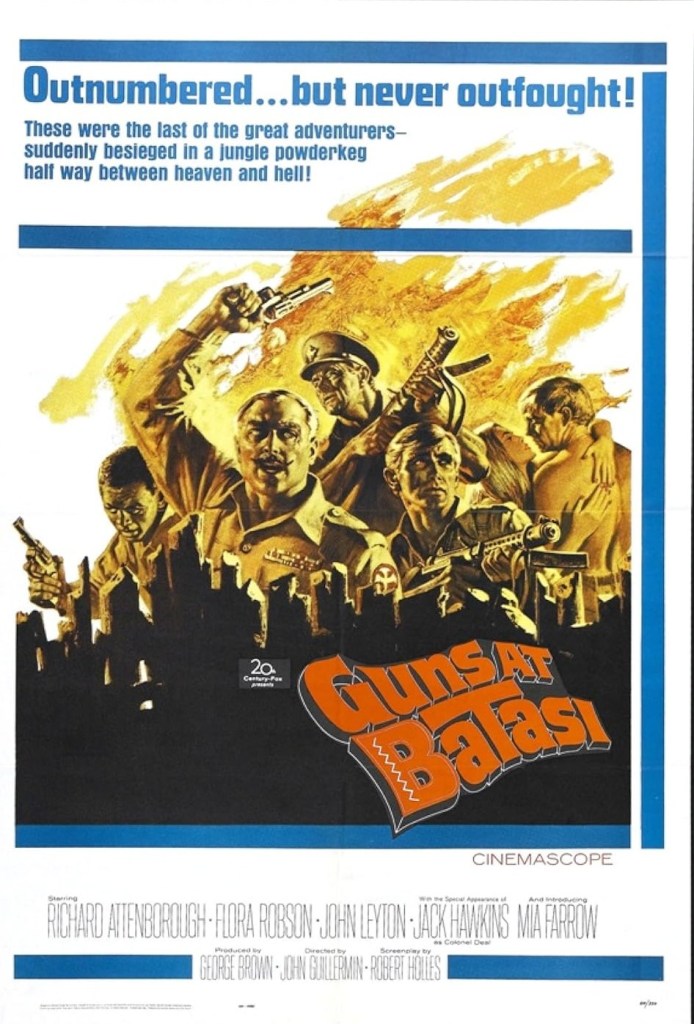

An excellent lead performance powers a solid film that slightly pulls it’s punches

Director: John Guillermin

Cast: Richard Attenborough (RSM Lauderdale), Jack Hawkins (Colonel Deal), Flora Robson (Miss Barker-Wise MP), John Leyton (Private Wilkes), Mia Farrow (Karen Eriksson), Cecil Parker (Fletcher), Errol John (Lt Boniface), Graham Stark (Sgt ‘Dodger’ Brown), Earl Cameron (Captain Abraham), Percy Herbert (Colour Sgt Ben Parkin), David Lodge (Sgt ‘Muscles’ Dunn), John Meillon (Sgt ‘Aussie’ Drake), Bernard Horsfall (Sgt ‘Schoolie’ Prideaux)

In the dying days of Empire, in an unnamed African nation, the British have agreed to a peaceful handover of power. Something that’s thrown out of kilter when an attempted coup takes place. That appals Regimental Sergeant Major Lauderdale (Richard Attenborough). His whole life has been keeping the peace in the colonies, making sure the mess is kept spick-and-span, drilling recruits, saluting portraits of the Queen and regretting he missed his chance to do his bit at Tobruk or El Alamein. A coup to him is nothing more than a mutiny, and harbouring the new overthrown government commander in the NCO’s mess from the troops looking to lynch him is both a matter of honour and (perhaps) a chance to fight his own little war preserving decency, honour and the British way.

Guns at Batasi is a fascinating slice of post-colonial film-making that succeeds as well as it does because it treats its lead character both as a sort of Blimpish moron and a tragic hangover whose Victorian principles are hideously out-of-step with the world around him. All of that is captured in Richard Attenborough’s rich, BAFTA winning, performance as he makes Lauderdale both faintly ridiculous (obsessed with neat collars, perfectly executed salutes and drill bullshit sitting) with an utter lack of interest in the world outside the parade ground and strangely likeable. He’s got a principled sense of right-and-wrong, a strangely affectionate regard for the soldiers he presses to the uttermost and an utter lack of cynicism or cruelty in his convictions.

It’s near career-best work by Attenborough, one well out of his wheel-house (at the time) of softly spoken eccentrics. In fact, he’s almost unrecognisable, transformed into a sort of walking bullet, rigid as his swagger stick and barking out his every utterance with a parade-ground bellow that emerges from a deep vocal bass. He’s a character soaking in absolute certainty, and Guns at Batasi gives him the dignity of letting him be both right and wrong without crowbarring in any moral judgement. Put bluntly, it trusts us to be intelligent enough to appreciate his determination to protect the lives of those under his care, just as we can feel uncomfortable at his parental attitude towards Africans.

Guillermin’s film places this bolted down man, absolutely certain of his understanding of the world, in two turmoils, one on-top of the other. Firstly, he’s the sort of bloke who wouldn’t have been out of place in the height of the Raj, barely able to believe that the British army (embodied by the decent, gentlemanly but subtly ineffective Colonel Deal expertly played by Jack Hawkins) doesn’t sweep everything before it anymore but has to negotiate with the locals. Secondly, he’s flung into the middle of a siege of the NCO’s mess, shepherding a mix of other sergeants, a young private (John Leyton) whose mocking 60’s swagger feels like he’s from a different planet and a painfully liberal visiting MP (Flora Robson) who feels Lauderdale is the problem not the solution.

Guns at Batasi builds its base-under-siege storyline very effectively, with Guillermin skilfully shooting a small set, interspersed with some well-staged action set pieces, not least Captain Abrahams (Earl Cameron) escape from his would-be lynch-mob. There is a neat sense throughout of a world pushing in on Lauderdale and his sergeants, from artillery pieces gathering on the lawn outside to an ever more searching series of questions for Lauderdale from the others about what exactly he thinks he’s preserving here. What’s well-handled about the film is you could see this as both Lauderdale making a stubborn stand that’s more about his pride than anything else, and a genuinely selfless noble attempt to save a persecuted man.

The film does slightly weight the deck in favour of Lauderdale. We warm to his witty sergeants-cunning to prevent the noble Abraham handing himself over to save lives (drafting a hugely wordy written order to do so, which he knows Abrahams will never stay conscious long-enough to sign). It’s hard not to sympathise with him, when the voice of liberalism is placed in the piously self-important lips of Flora Robson’s MP who insists, until she’s finally shown she’s terribly wrong, that coup lickspittle Lt Boniface (Errol John) isn’t the ruthless two-faced man-of-no-honour he so plainly is. It’s hard not to sympathise when Lauderdale tears Boniface off a titanic strip (a tour-de-force moment from Attenborough) or hard not to admire the professional pride in his duty to keep others safe.

If you could criticise the film, it gives less scope to putting into an explicitly critical viewpoint or giving much scope to Lauderdale’s probably less charming or attractive features. You could well imagine that, returning to Blighty, his attitudes could curdle into an unattractive ‘Britain First’ attitude. Sure, we are encouraged to see his obsession with perfectly ironed uniforms and the exact perfection of a salute as something quite silly. But he’s also a man who doesn’t question for a minute Britain’s inherent superiority or its right to dominate large chunks of the globe. But Guns at Batasi lacks a real character who challenges Lauderdale – even Leyton’s cheeky private ends up being adopted in an affectionate strict-fatherly way by the RSM, rather than someone who could really signpost Lauderdale’s relic nature or the potentially darker implications of his character. Just as the film treats the other sergeants lack of knowledge or interest in this country (right down to continually mis-pronouncing the local town as Battersea) as comedic rather than an insight into underlying complacent understanding as the world being a place run by and for the British.

But the film stands out as one of the best acting showcases Attenborough ever had, a swaggering role of bombast that he absolutely rips through while humanising it. There are great supporting turns from Horsfall, Herbert, Lodge and Mellion as wildly different types of sergeant and the film manages to be both quietly satirical, nostalgic and pack in some derring-do along the way. If it doesn’t quite manage to really seize on its potential, it’s still an interesting film.