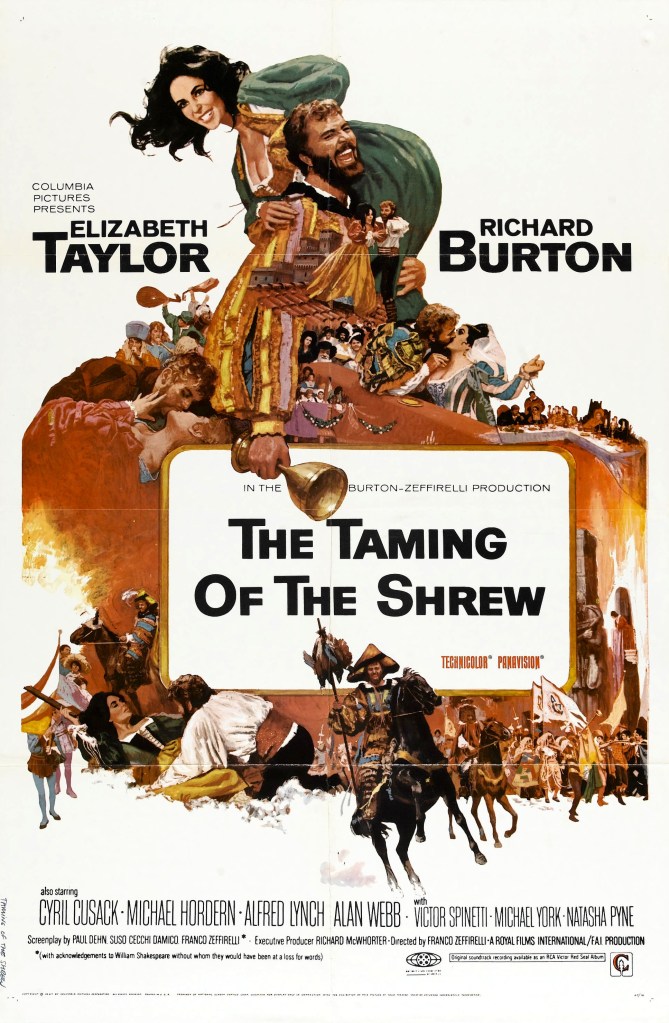

Burton and Taylor are perfect casting in this rollicking adaptation of Shakespeare’s most difficult comedy

Director: Franco Zeffirelli

Cast: Elizabeth Taylor (Kate), Richard Burton (Petruchio), Cyril Cusack (Grumio), Michael Hordern (Baptista Minola), Alfred Lynch (Tranio), Alan Webb (Gremio), Michael York (Lucentio), Natasha Pyne (Bianca), Victor Spinetti (Hortensio), Roy Holder (Biondello), Mark Dignam (Vincentio), Vernon Dobtcheff (Pedant), Bice Valori (Widow)

There’s a reason why the poster screamed “The motion picture they were made for!” Who else could play literature’s most tempestuous couple, than the world’s most tempestuous couple? After all, they rolled into this straight off the success of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and, say what you like, a knock-about piece of Shakespearean farce is certainly more fun than two hours of Edward Albee. So, Burton and Taylor turned up in Italy, entourage in hand, to bring The Taming of the Shrew to life in a gorgeous explosion of grand sets and wonderfully detailed costumes.

The Taming of the Shrew actually translates well to the screen – and Zeffirelli’s high-octane style. Odd to think now, for a film soaked in elaborate period setting, that in the 60s Zeffirelli’s style was seen as border-line sacrilegious to the Bard. He actually escaped with less opprobrium from the critics than he faced for cutting two-thirds of Romeo and Juliet a year later, since most seemed to think Shrew was less of a holy text. Not that it stopped a lot of critics reckoning Zeffirelli should focus more on executing every pentameter to perfection and less on gags and visual story-telling.

But actually, that’s perfect for a story that was always a raucous farce at heart – so much so, even the original play presents it as a play-within-a-play told to a drunken Christopher Sly (cut here). The bawdiness feels fresh out of Chaucer and Boccaccio, a parade of people in period costumes slapping thighs, roaring with laughter, double taking and enjoying a series of cheeky jokes (did Pasolini watch this before making his lusty adaptations?). Padua is a city of sin, with prostitutes openly advertising their wares (and later, clearly, invited to Bianca’s wedding) and a wife-stealer is in the stocks.

Zeffirelli’s Shrew is full of rowdy wildness – in a nod to the cut Sly framing device, Padua is in the midst of a feast of fools, students turning a choral sing-along into a drunken celebration. Kate and Petruchio’s high-octane gunning for each other, feels fitting for a location where everyone is careering wildly towards the target of their immediate emotions, either horny beyond belief, desperate to marry off daughters or furious at supposed crimes or betrayals.

The age-old question you have when staging Shrew is what to do about its fundamental misogyny (and it’s hard not to argue, much as the bard’s defenders have tried, not to see it as a play deeply rooted in the patriarchy). Zeffirelli’s solution is an intriguing one: his Shrew is enigmatic, with Kate’s motivations, feelings and reasonings often left cleverly open to interpretation. It’s also helped, of course, by the natural chemistry between the two leads. If there is one thing we all know, it’s that Burton and Taylor were really into each other and drove each other up the wall. What Shrew does here is take that sexual force and exuberance of its leads and balances that with a subtle unreadable quality to Kate that leaves the relationship’s power-balance just open enough to interpretation.

In addition, the film makes clear Kate’s behaviour is unacceptable, introduced screaming abuse from a window and smashing up all the furniture in a room in a fit of furious pique. There’s a lovely touch where Petruchio stares into his own reflection, while planning his campaign – a nice suggestion that he will mirror her behaviour to show its unacceptability (indeed, on returning to their marriage home, he’ll also twice smash up a room’s contents in a pointless display of adolescent petulance). Kate has, to put it bluntly, anger management issues and if Petruchio’s methods are extreme you can see the twisted logic.

Their first meeting sets a pacey tone that will run through the whole film. It’s a wild chase through the Baptista home, through a connected wool barn, over a roof and back again. One in which they will bellow at each other, Kate will rip up planks and bannisters to throw at him, they’ll roll in the wool (hard not to see a sexual charge here) and eventually collapse through the roof to land back in the wool. Petruchio will then announce her consent to marry with an arm twisted round her back, just as he will cut off her refusal at the altar with a kiss (the wedding scene is a neat interpolation, showing something the Bard only reports). They are in a constant pursuit of sorts from here, from the back-and-forth at Petruchio’s house, to the journey to Padua and then finally through a crowd of women at the film’s end. But where does the power lie: pursued or pursuer?

At first, of course, with the pursuer. Burton’s Petruchio is a wild-eyed force-of-nature, permanently partly sozzled (Burton spends most of the film with a pale, damp drinking sweat that was probably not acting), his tights full of holes, his manners rude (he’s basically Christopher Sly in the lead role), focused on the money he’ll get from wooing Kate. But, while he’s a powerful alpha male, it’s remarkable how the balance slowly shifts to Kate. After their arrival at his home (she, soaking wet after falling in a puddle to Petruchio’s laughter), she puts her drunken husband to bed, has the house redecorated, the servants redressed and everything arranged to her liking.

Taylor’s performance here adds to the effect. It’s an intelligent, camera-wise performance which uses looks to convey Kate’s loneliness and pain. Locked in a room before the wedding, she glances out of a window with aching sadness. She looks with gentle envy at warm friendship in others. Taylor gives a wonderfully calm, genuine delivery of the famous closing speech of wifely piety. But it’s words are undermined in two ways: firstly by the suspicion it’s partly done to show-up the jokes against her throughout the wedding, and then by Taylor’s immediate departure after kissing a finally flabbergasted Petruchio, leaving our macho hero wading through a pile of laughing women in a desperate attempt to catch-up. Who might just rule here, long term?

Zeffirelli’s film moves the Lucentio (a wide-eyed Michael York) sub-plot even further to the margins – in a neat invention, Petruchio during the first chase, keeps barging in on rooms where different sub-plot scenes are all going on at the same time. As a result, this does mean a number of first-rate actors get very little to do: Cyril Cusack’s Grumio becomes a grinning observer of the chaos, Alfred Lynch’s Tranio (after some initial fourth-wall breaking) fades into the background, Michael Hordern has little to do but look aghast as a desperate Minola, Alan Webb barely registers as a rejected suitor while after an initial sight gag (his minstrel player disguise making him look like the fifth Beatle) Victor Spinetti gets similarly fades away.

But then audiences were here for the Burton-Taylor show, and they get that in spades: framed within a medieval setting inspired by classical painting (and which features an obviously fake backdrop for its countryside exteriors). And The Taming of the Shrew is rollicking good fun, which manages to work an interesting line on the play’s troublesome sexual politics, suggesting that all but not always be as it seems. And it nails the atmosphere of rollicking fun in this ribald Shakespeare yarn.