The importance of journalism is loudly praised in this engaging but faultlessly liberal Clooney film

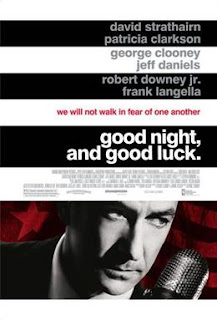

Director: George Clooney

Cast: David Strathairn (Edward R Murrow), George Clooney (Fred Friendly), Robert Downey Jnr (Joseph Wershba), Patricia Clarkson (Shirley Wershba), Frank Langella (William Paley), Jeff Daniels (Sig Mickelson), Tate Donovan (Jesse Zousmer), Ray Wise (Don Hollenbeck), Helen Slayton-Hughes (Mary), Alex Borstein (Natalie), Thomas McCarthy (Palmer Williams)

In the early 1950s America seemed to be in the paranoid grip of one man. Senator Joseph McCarthy was the tip of a spear of anti-Communism, targeting every part of American life. To have even had thoughts that might be seen as socialist or communist, was enough for you to be considered an Anti-American and potential enemy of the state. McCarthy led a campaign to unearth Communist spies and sympathisers in the government, military, business, academia and the media. Blacklists and persecution were rife, and the slightest past association could condemn you. It took many years before anyone took a stand against this.

One of the leaders of this stand was renowned journalist Edward R Murrow (David Straithairn). Famous for his broadcasts from London during the Blitz, Murrow hosted an investigative journalist programme See It Now. A passionate believer in the power of television to educate and inform, Murrow and his producer Fred Friendly (George Clooney) are appalled when Air Force officer Milo Radulovich is condemned to be discharged, based on members of his family being communists and a sealed envelope of charges he was never allowed to see. Despite the worries of network CBS, Murrow, Friendly and their team run an episode of the show that exposes McCarthyism and its injustice, the first of several investigating McCarthy. But what price will they pay?

Clooney’s well-made, heartfelt film, is an impeccably liberal piece of film-making that is a very sincere tribute to the potential of television to be more than just an idiot’s lantern. Clooney frames the film with Murrow accepting a lifetime achievement award in 1958: he uses the opportunity to make a speech rebuking the room full of executives and journalists for squandering the potential of television to inform rather than just entertain. Murrow would of course be horrified by what TV became. Good Night, and Good Luck is a rose-tinted view of television journalism at its pioneering best: just as the end result of See It Now being gutted by cuts is a realistic look at where the scales will fall if entertainment and money are balanced with principles and education.

Clooney’s father was a TV journalist, while Clooney himself majored in journalism. The cut-and-thrust of the newsroom is as intrinsic to him, as is a desire to investigate and inform as part of a healthy political debate. Good Night, and Good Luck captures the mood of a newsroom with a convincing confidence. Journalists debate the fine point of stories, editors rush to assemble films and executives balance the pros and cons. It’s all shot in a beautiful monochrome, that exquisitely captures the haze of cigarette smoke all this takes place in. It’s a shot with a handheld urgency, sharply cut, that puts us into this world of cut-and-thrust media decisions.

And it makes clear what TV news can be. Not agenda led, but facts led. Not kowtowing to power, but challenging it to justify itself. Looking into matters that are important, not sensational. Wanting to inform people and expand their understanding, rather than pander to the lowest common denominator. Murrow’s shows are scrupulously fact-checked, and allow full rebuttal from their subject. He comes at story not with a pre-supposed position, but based on where the facts and his editorial judgement leads him.

It all takes place in a TV set that’s really striking in its humbleness, compared to the operatic news sets we see today. The 1950s studio is small, cramped and simple – and by contrast the ideas are large, expansive and complex. Murrow’s set is little more than a chair with a TV monitor. His producer Fred Friendly, literally sits at his feet to hand him notes and cue him in with announcements and VT. The See It Now set contrasts vividly with the more grandiose sets for Murrow’s other show, a series of puff piece interviews with popular stars like Liberace. (While Murrow learns his scripts by heart for See it Now, he professionally reads through a series of cue cards for these for-the-money interviews).

Murrow and Friendly also won’t compromise. They defend their right to make the show to CBS President William Paley (a brilliant performance from Frank Langella), who prides himself on no direct intervention on the news but pushes for a less controversial line. The entire team is consulted on every issue. The newsroom is a place where our better angels can come out.

But it’s still happening in an America where people are careful about what they say and do. A subplot concerns reporters played by Robert Downey Jnr and Patricia Clarkson: secretly married – contrary to CBS policy – like those suffering from McCarthyism, they must live a lie in order to protect what they have. See It Now is in danger of criticism, cancellation and attack. Another CBS anchor, Don Hollenbeck – perfectly played by Ray Wise (and few actors are better at suppressed desperation than Wise) – is dealing with constant media persecution for his perceived communist sympathy. Murrow and Friendly are not perfect: they sometimes dodge the fights they can’t win and Murrow in particular shrugs off or ignores Hollenbeck’s concerns with tragic results.

But, as Clooney makes clear, the good outweighs all the rest. As Murrow, David Straithairn (Oscar-nominated) has never been better. He perfectly captures Murrow’s mannerisms, but mixes it with wonderful measure of honesty and decency, mixed with a degree of pride and self-righteous certainty. He dominates the film (with Clooney as a generous foil) and carries much of the film’s liberal message that smart, intelligent, dedicated men can change the world.

Good Night, and Good Luck might be the most soft-left liberal film made in Hollywood in the last fifteen years. But it is a fine example of film-making craft and the earnest honesty with which it is made in its own way inspiring. It’s Clooney’s finest film and it’s grounded in his strengths: fine actors and writing carrying a sincerely told message.