The Devil sure knows how to tempt a man in this beautifully filmed morality tale

Director: William Dieterle

Cast: Walter Huston (Mr Scratch), Edward Arnold (Daniel Webster), James Craig (Jabez Stone), Anne Shirley (Mary Stone), Jane Darwell (Ma Stone), Simone Simon (Belle), Gene Lockhart (Squire Slossum), John Qualen (Miser Stevens), HB Warner (Judge Hawthorne)

Sometimes life can be a real struggle. With debts, failed crops and animals getting sick, what’s a guy to do? That’s the problem New Hampshire farmer Jabez Stone (James Craig) has in 1840. What he wouldn’t give to find a bundle of buried gold that could solve all his problems. Fortunately, charming old rogue Mr Scratch (Walter Huston) knows exactly where to find one – all he wants in return is for Jabez to sign away his soul seven years from now (signed in blood of course). Jabez gets fortune, prestige, the son he always wanted – but when ‘Mr Scratch’ comes to collect, can Jabez’s friend, famed orator, lawyer and congressmen Daniel Webster (Edward Arnold) save his soul?

All That Money Can Buy is a richly atmospheric piece of film-making from William Dieterle, adapted from Stephen Vincent Benet’s short story and full of gorgeously filmed light-and-shadow with a haunting score by Bernard Herrmann. (The story was originally titled The Devil and Daniel Webster, also the film’s original title before RKO changed it to avoid confusion with their more successful Jean Arthur comedy The Devil and Miss Jones.) It’s a neat morality tale, full of dark delight at the devilish ingenuity of Mr Scratch, with lots of dark enjoyment at seeing a weak-but-decent man corrupted into being exactly the type of greedy, cheating cad to whom he was deeply in debt to from the beginning.

It’s nominally about James Craig’s Jabez Stone, but Jabez is a shallow, easily manipulated passenger in his own life, pushed and pulled towards and away from sin depending on who he’s talking to. Stone’s fall is swift: moments after meeting Scratch, he’s digging hungrily into a meal while his wife and mother say grace, hugging his newfound bag of gold. As his wealth goes, he drifts from his pure wife (Anne Shirley, effective in a dull part) becoming easy prey for demonic (literally) temptress Belle (a wonderfully seductive Simone Simon). By the time the seven years are up, he’s skipping church for illicit card games and crushing the farms of his neighbours to fund his dreamhouse-on-a-hill.

Stone is really the Macguffin here. The real focus is the big-name rivals: The Devil and Daniel Webster. It’s implied these two have fought a long-running battle for years: our introduction to Webster sees him scribbling literally in the shadow of Mr Scratch, who whispers to him tempting offers of high office. Later Webster is unflustered when Scratch suddenly appears to place a coat on his shoulders, treating him as familiar rival. You could argue Scratch is only prowling the streets of New Hampshire because he’s looking for a way to nail the soul of his real target, Daniel Webster.

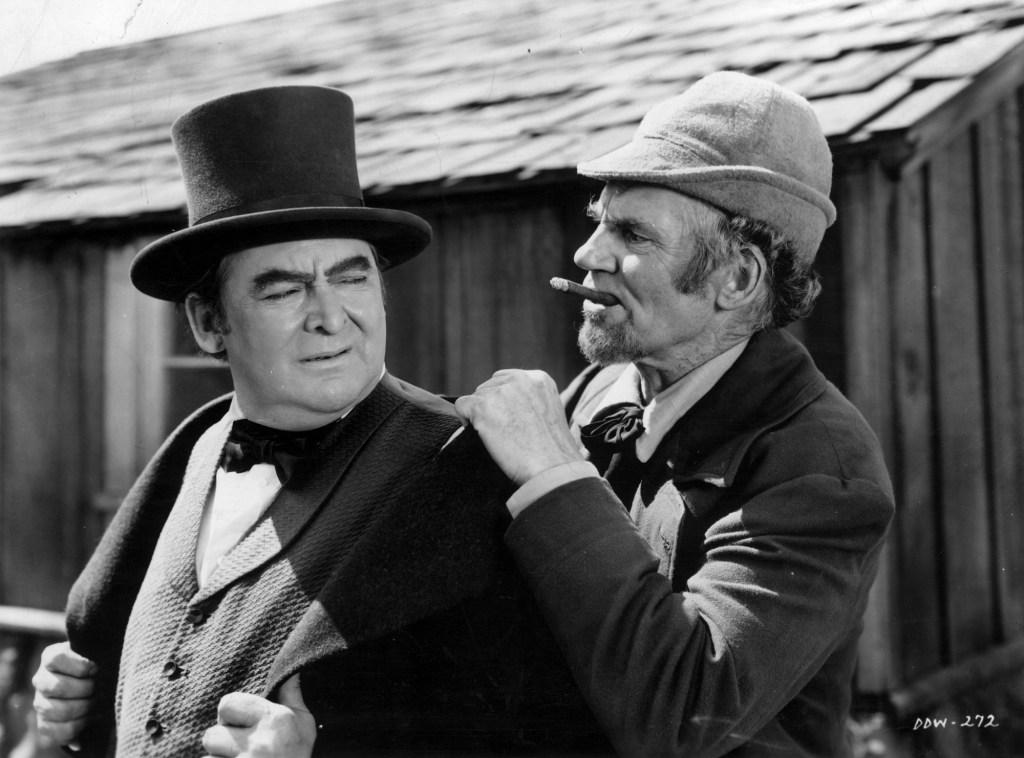

As Mr Scratch, the film has a delightful (Oscar-nominated) performance from Walter Huston. With his scruffy clothes and twirling his cane, Scratch pops up everywhere with Huston’s devilish smile. It’s a masterclass in insinuating, playful malevolence, with Huston playing this larger-than-life character in a surprisingly low-key way that nevertheless sees him overflowing with delight at his own wickedness. Huston has the trick of making Scratch sound like someone trying to sound sincere, while never leaving us in doubt that everything he says is a trap or lie, only showing his arrogance and cruelty when victory is in his grasp. It’s a fabulous performance, charismatic and wicked.

Edward Arnold makes Daniel Webster both a grand man of principle and a consummate politician, proud of his reputation and all the more open to temptation for it. He also has the absolute assurance of a man used to getting his own way, and the arrogance of seeing himself as an equal to the Devil rather than a target. These two form the ends of a push-me-pull-me rivalry.

The rivalry culminates in its famous ‘courtroom’ scene, as Webster – a little the worse for drink –argues for Jabez’s soul in front of a ghostly court of American sinners from the bowels of hell (lead among them Benedict Arnold). Its shot in atmospheric smoke, with the double exposure creating a ghostly effect for jury and judge. It’s another excellent touch in a film full of inventive use of effects and camerawork, Dieterle at the height of his German influences. The artificial New Hampshire scenery is shot with a sun-kissed beauty that bears Murnau’s mark. Striking lighting and smoke-play abounds in Joseph H August’s camerawork, not least Belle’s introduction backlit with an extraordinarily bright fire. Early scenes of Stone’s misfortune interrupted by a brief frames of a photo-negative Scratch laughing, quite the chillingly surrealist effect.

Politically, All That Money Can Buy backs away from any overt criticism of Webster’s support for the Missouri Compromise (this key piece of slavery protection legislation is so key to Webster’s view of American strength he’s even named a horse after it). But it’s quite brave for 1941 in allowing the Devil legitimate criticism of America’s ‘original sins’ saying he was there driving on the seizing of the land from the Native Americans and up on deck on the first slave ship from the Congo. (Especially as Webster can’t defend these actions). It’s also interesting that the film praises collectivism for the farmers over rugged individualism, a conclusion it’s hard to imagine being praised a few years later.

All That Money Can Buy is also filled with impressive practical effects, not least Scatch’s impossible catching of an axe thrown towards him, bursting it into frame. Both Scratch and Bell reduce papers to flaming ashes with a flick of the wrist. Horribly woozy soft-focus camera work accompanies Jabez’s nightmare visions of the damned. It’s tightly and skilfully edited, superbly paced, with montages used effectively for transitions (a field of corn growing is particularly striking) and wildly unnerving sequences, like Scratch’s fast-paced barn-dance with its whirligig of movement and repeated shots. It’s all brilliantly scored by Herrmann, from the pastoral beats of New Hampshire to the discordant sounds (some created from telephone wires) that accompany Scratch.

All That Money Can Buy concludes with a stand-out speech from Webster that perhaps settles matters a little too easily – and brushes away any of the film’s mild criticism of America’s past with a relentlessly upbeat patriotic message. But the journey there – and the performances from a superb Huston and excellent Arnold – is masterfully assembled by a crack production team working under a director at the height of his powers. A flop at the time, few films deserve rediscovery more.