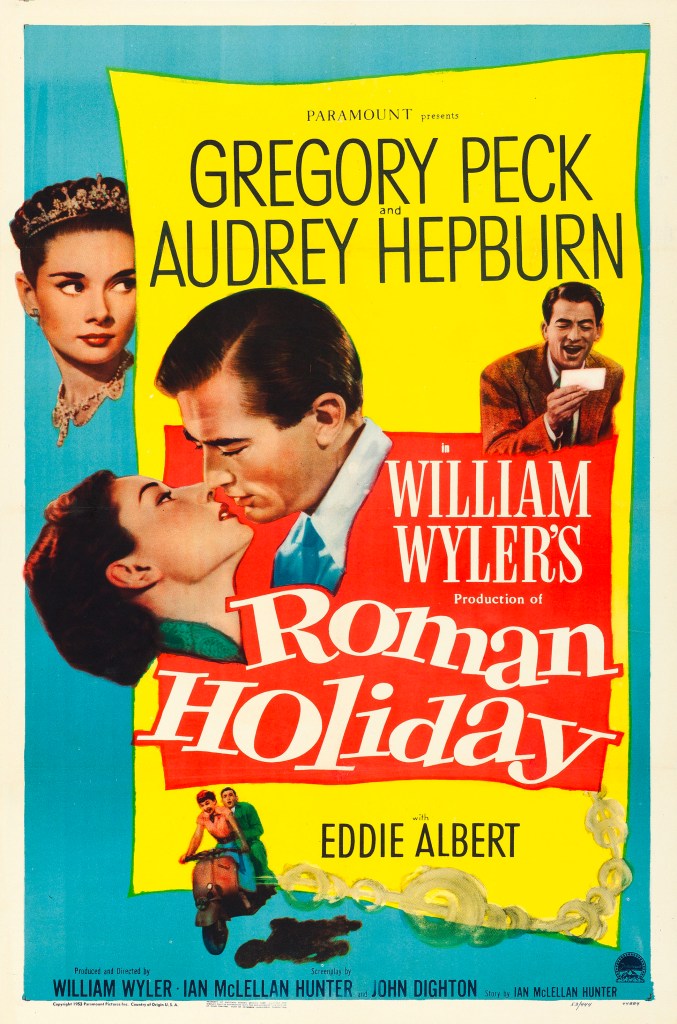

Gorgeously light romantic comedy that invented and mastered a whole genre

Director: William Wyler

Cast: Gregory Peck (Joe Bradley), Audrey Hepburn (Princess Ann), Eddie Albert (Irving Radovich), Hartley Power (Hennessey), Harcourt Williams (Ambassador), Margaret Rawlings (Countess Vereberg), Tullio Carminati (General Provno), Paulo Carlini (Mario Delani), Claudio Ermelli (Giovanni), Paola Borboni (Charwoman), Alfredo Rizzo (Taxi driver)

Everyone loves a fairy tale, which is probably why Roman Holiday remains one of most popular films of all time. The whole thing is a care-free, romantic fantasy in a beautiful location, where it feels at any time the chimes of midnight could make the whole thing vanish instantly in a puff of smoke. It’s like a holiday itself: a chance to immerse yourself in something warm, reassuring and utterly charming. This fairy tale sees a Princess escape to freedom. Only she’s not escaping imprisonment by some ghastly witch or terrible monster: just from the relentless grind of never-ending duty.

The heir to the throne of an unnamed country (one of those Ruritanian neverwheres you’d find in a Lubitsch movie), Princess Anne’s (Audrey Hepburn) every waking moment is a never-ending parade of social and political functions. Just for once she’d like to do what she wants to do for the day. Something she gets when she escapes into Rome (after being given a dopey-inducing drug to sleep) and finds herself in the company of American newshound Joe Bradley (Gregory Peck). Joe quickly works out he’s harbouring the most famous woman in the world and dreams of the scoop of the century. Pretending not to know ‘Anya’s’ identity, they spend the day shooting the breeze in Rome – only to find themselves falling in love. Will Joe sell the story? And will Ann stay free or return to her duties?

Truth be told, like many fairy tales, it’s a very light story that leads towards familiar (and reassuring) morals, with a big dollop of romance along the way. It works however, because it’s told with such lightness, playfulness and gentle innocence, that it washes over you like a warm bath. A director like Lubitsch would have found sharper wit (not to mention sexual tension) in the material, but Wyler’s decision to hold back arguably works better. It lets the magic of the plot weave without directorial flourishes overbalancing things. It works because it’s so soft touch and unobtrusive in its making that it allows the actors to flourish.

It helps as well that they had Audrey Hepburn. Hepburn’s entire life changed with Roman Holiday (surely the last time she could have walked through Rome unnoticed!), winning an Oscar for the sort of dream-fit role that comes once in a blue moon. Hepburn looks perfect as a fairy-tale Princess, but her performance succeeds because of her gift for light comedy and flair for slapstick. She’s an acutely funny and hugely endearing performer, and your heart warms to her instantly. From stretching her foot and losing a shoe (under her billowing dress) in the film’s opening reception, Hepburn launches into a perfect low-key comic routine as she attempts to restore it. That comic physicality carries through her doped-out first night of freedom, including an impressive roll across a bed into a sofa, fully committed to the word-slurring ridiculousness. She’ll bring the same daft energy to her disastrous Vespa riding. Hepburn has become such an icon of class, it’s easy to forget what a bouncy comedian she was.

These comic touches make us root for her, and it’s made even easier through Hepburn’s ability to make naivety combined with touches of austere distance effortlessly charming. Watching her react with blithe confusion (and then charmingly embarrassed realisation) as she accepts shoes and flowers from retailers without realising they expect payment is never less than charmingly hilarious. Her wide-eyed excitement at everyday things like ice cream or getting an (iconic) haircut is winningly loveable. You find it funny rather than frustrating that she expects help undressing (much to Joe’s flustered surprise) or for problems like policemen to melt away. Hepburn’s performance is nothing less than transcendent, a sprinkle of Hollywood magic.

Opposite her, the film wisely casts that bastion of decency Gregory Peck. Other actors would have leaned into Joe’s background as a fast-living reporter constantly in hock to a parade of gamblers, landlords and newspaper editors. But Peck is so clean-cut he feels like Walter Cronkite on leave and removes any audience concern that Joe might do something caddish. We never once feel for a moment Anne is at risk of being taken advantage of when she sleeps in his apartment (would we have felt the same certainty with, say, Tony Curtis or even Cary Grant?) and Peck is so straight-shootingly decent, the implied threat that he may betray Anne by reporting her day of freedom as a glossy tell-all of outrageous behaviour very easily drifts from the audiences mind when watching the film. We all know Peck would never do that!

All this allows us to fully relax and enjoy the bulk of the film, which is essentially watching two beautiful, likeable people have a lovely day looking among the gorgeous sights of the Eternal City. It’s hard to credit it, but the Roman authorities initially refused the right to film as they were worried it would demean the city. Just as well they changed their mind, as perhaps no film has driven more people to Rome. Roman Holiday (even the title is a subliminal suggestion to the viewer) is full of wonderful locations, from the Trevi fountain to the Spanish steps and it single-handedly turned the Mouth of Truth into a must-visit tourist spot – not surprising, as Peck’s improvised pretence to lose his hand and Hepburn’s wails of laughter are one of the film’s most lovable moments.

Moments like that showcase the natural warmth and chemistry between the two actors, and Roman Holiday leans into it to create one of the most romantic films ever made. There is a genuine palpable spark between the two, from their meet-cute in a taxi (a dopey Anne confusedly mumbling that she lives in the Colosseum) to the ice melting between them, to the little glances they give each other as they make each other laugh on Vespas or their bond growing as throw themselves into fending off a parade of besuited goons from Anne’s embassy (this moment includes the hilarious moment when Hepburn bashes a goon over the head with a guitar).

It’s all leading of course to the inevitable bittersweet ending – because, such is the decency of Peck and Hepburn, we know they are never really going to chuck it all aside when duty and doing the right thing calls – which is equally delivered with a series of micro-reactions at another interminable function that is genuinely moving in its simplicity. Even Eddie Albert’s hilariously cynical photojournalist gets in on the act.

It’s the perfect cap to a wonderfully entertaining, escapist fantasy which never once leaves you anything less than entertained. You could carp that there is never any threat or peril at any point – and that the paper-light plot breezes by – but that would be to miss the point. But Roman Holiday invented and mastered a Hollywood staple: two likeable people fall in love in a gorgeous location. And who hasn’t dreamed of a holiday like that?