Garbo is at her best in this luscious, romantic, beautifully filmed historical epic

Director: Rouben Mamoulian

Cast: Greta Garbo (Queen Christina), John Gilbert (Antonio Pimental de Prado), Ian Keith (Count Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie), Lewis Stone (Axel Oxenstierna), Elizabeth Young (Countess Ebba Sparre), C. Aubrey Smith (Aage), Reginald Owen (Prince Charles Gustav), David Torrence (Archbishop), Gustav von Seyffertitz (General), Akim Tamiroff (Pedro)

What could be more perfect casting than Garbo as Queen of Sweden? In Queen Christina she plays the eponymous queen, daughter of legendary martial monarch Gustavus Adolphus, killed in the never-ending European bloodbath that was the Thirty Years War. Coming to the throne as a child of six, almost twenty years later she’s ready for peace in Europe. But, after a lifetime of duty, she’s also ready for something approaching a regular life. But her lords need her to do something about providing an heir, ideally by marrying her heroic cousin Charles Gustav (Reginald Owen) despite the fact she’s conducting her latest secret affair with ambitious Count Magnus (Ian Keith). One day Christina sneaks out of town, dressed as a man and meets (and spends several nights with – the disguise doesn’t last long) Spaniard Antonio de Pradro (John Gilbert) in a snowbound inn. Returning to court she has a difficult decision: love, duty or a bit of both?

Queen Christina is a luscious period romance with Garbo in peak-form. It’s a masterful showpiece for a magnetic screen presence and charismatic performer. Queen Christina gives Garbo almost everything she could wish: grand speeches, coquettish romance, Twelfth Night style romantic farce, domineering regal control and little-girl lost vulnerability. Garbo brings all this together into one coherent whole, and is a dynamite presence at the heart of Queen Christina. Garbo nails the show-stopping speeches with regal magnetic assurance, but will be delightfully girlish when giggling with lovers. Her nervousness that her femineity could be unmasked in any moment with Antonio in the inn is played with a charming lightness that’s deeply funny, while the romantic shyness and honesty she displays with him is pitched just right. Garbo also manages to make the queen never feel selfish even as she is torn between desire and duty.

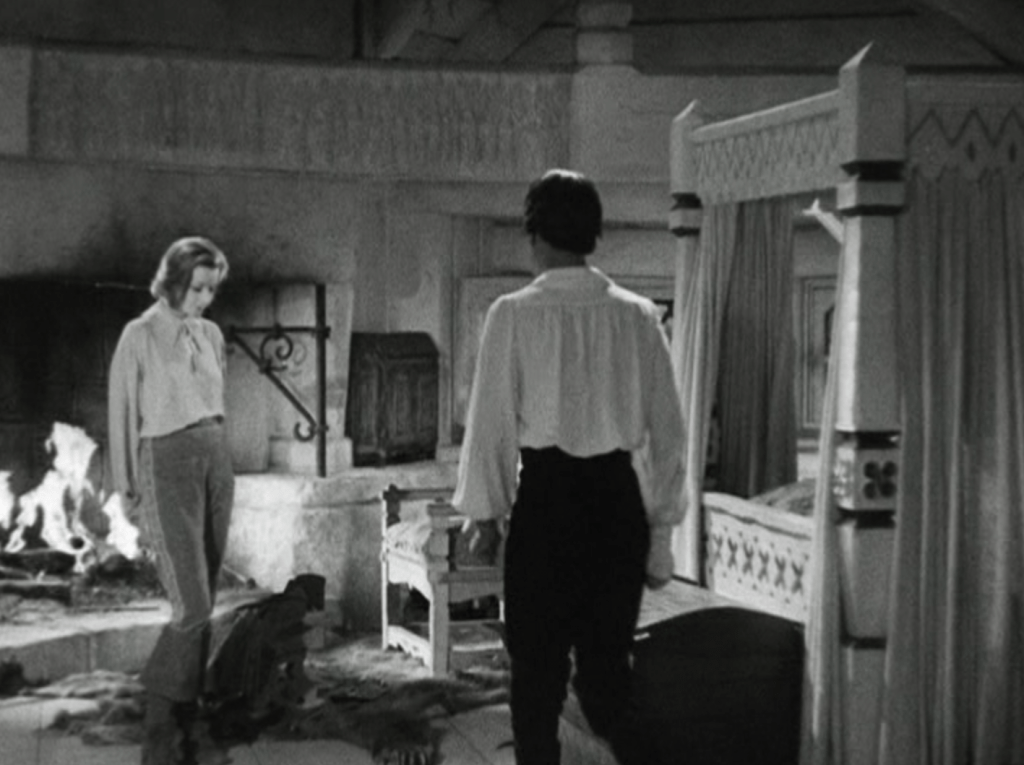

She’s at the centre of a beautifully assembled film, gorgeously shot by William H Daniels, with dynamic camera movements, soaking up the impressive sets and snow-strewn locations. Rouben Mamoulian’s direction is sharp, visually acute and balances the film’s shifts between drama and comedy extremely well – it’s a remarkable tribute that considering it shifts tone and genre so often, Queen Christina never feels like a disjointed film or jars when it shifts from Garbo holding court in Stockholm, to nervously hiding under her hat in a snowbound inn to keep up the pretence she’s just one of the guys. (How anyone could be fooled for even a moment into thinking Garbo was a boy is a mystery).

It’s a relief to Antonio to find she isn’t one of the guys, since he’s more than aware of the chemistry between the two of them when he thinks she is one. There more than a little bit of sexual fluidity in Queen Christina, with Garbo’s Queen clearly bisexual, sharing a kiss with Elizabeth Young’s countess in ‘a friendship’ that feels like a lot more. Even before escaping court, Christina’s clothes frequently blur the line between male and female, as does the way she talks about herself. She is after all, very much a woman in a man’s world. Garbo brilliantly communicates this tension, her face a careful mask that only rarely slips to reveal the strain and uncertainty below the surface. You can see it all released when she stands, abashed, nervous (and unequivocally not a boy) in front of Antonio, as if showing her true self to someone for the first time.

Seizing not being the figurehead of state but her own, real, individual is at the heart of one of Queen Christina’s most memorable sequences. After several nights of passionate, romantic love making with Antonio, Christina walks around the inn room where, for a brief time, she didn’t have to play a role. With metronomic precision, Mamoulian follows Garbo as she gently caresses surfaces and objects in the room, using touch to graft the room onto her memory, so that it can be a place she can return to in her day-dreams when burdened by monarchy. It’s very simply done, but surprisingly effective and deeply melancholic: as far as Christina knows, the last few days have been nothing but in an interim in a life where she must always be what other people require her to be, never truly herself.

But then if she never saw Antonio again, there wouldn’t be a movie would there? He inevitably turns up at court, presenting a proposal from the Spanish king – which he hilariously breaks off from in shock when he clocks he is more familiar with the Queen than he expected. John Gilbert as Antonio gives a decent performance – he took over at short notice from Laurence Olivier, who testing revealed had no chemistry with Garbo – full of carefully studied nobility. He and Garbo – not surprising considering they long personal history – have excellent chemistry and spark off each other beautifully. He also generously allows Garbo the space to relax as Christina in a way she consciously never truly does at any other point in the film.

The rumours of this romance leads to affront in Sweden, from various lords and peasants horrified at the thought of losing their beloved Queen – and to a Spaniard at that! (Queen Christina makes no mention of the issue of Catholicism, which is what would have really got their goat up – an Archbishop shouts something about pagans at one point, but he might as well be talking about the Visigoths for all the context the film gives it). The shit is promptly stirred by Ian Keith’s preening Count Magnus, making a nice counterpart to Gilbert’s restrained Antonio. It also allows another showcase for Garbo, talking down rioting peasants with iron-willed reasonableness only to release a nervous breath after resolving the problem.

Queen Christina concludes in a way that mixes history with a Mills-and-Boon high romance (there is more than a touch of campy romance throughout). Mamoulian caps the film with a truly striking shot, the sort of image that passes into cinematic history. Having abdicated into a suddenly uncertain future, Christina walks to the prow of the ship carrying her away from Switzerland. Mamoulian holds the focus on Garbo and slowly zooms in, while Garbo stands having become (once again) a literal flesh-and-blood figurehead, her eyes gloriously, searchingly impassive leaving the viewer to wonder what is going on in her head? Is she traumatised, hopeful, scared, regretful, determined? It’s all left entirely to your own impression – and is a beautiful ending to the film.

Queen Christina was a big hit – bizarrely overlooked entirely at the Academy Awards, which makes no sense to me. It’s beautifully filmed by Mamoulian who finds new, unique angles for a host of scenes and at its heart has a truly iconic performance by Garbo. If you had any doubts about whether she was a great actress, watch Queen Christina and see how thoughts and deep emotions pass briefly across her face before being replaced by a mask of cool certainty. It’s a great performance from Garbo and a lusciously conceived historical epic.