Early Talkie Western has moments of invention, around some awkwardly dated acting and plotting

Director: Irving Cummings, Raoul Walsh

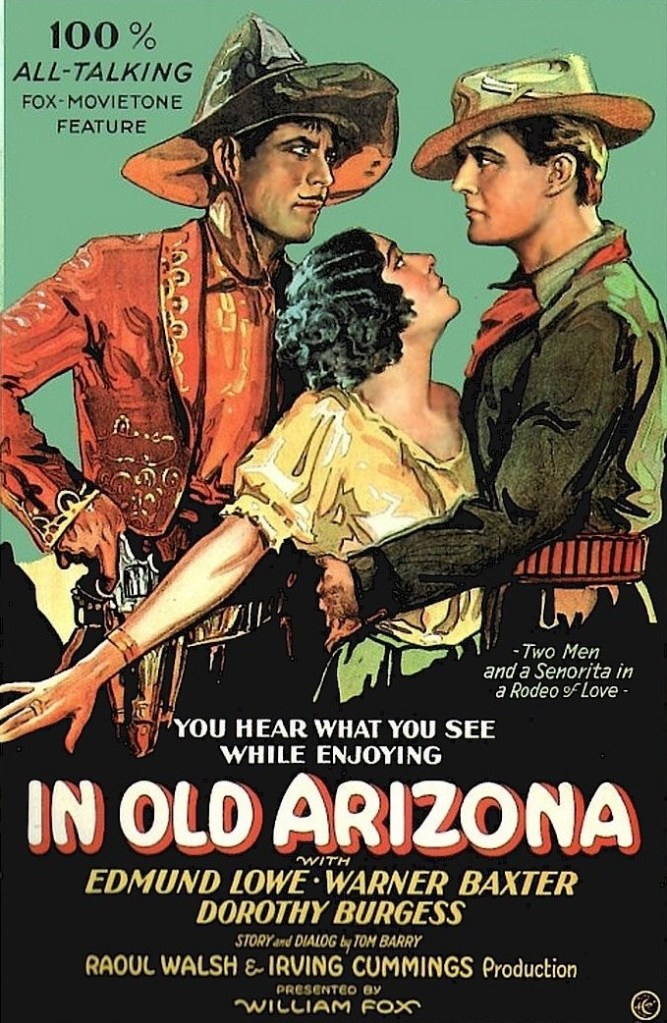

Cast: Warner Baxter (The Cisco Kid), Edmund Lowe (Sergeant Mickey Dunn), Dorothy Burgess (Tonia Maria)

In Arizona, is a public nuisance is plaguing the authorities: The Cisco Kid (Warner Baxter), a charming bandit who holds up stagecoaches, flirts with women and evades the lawmen with a swagger and a smile. But he’s a decent thief: he only takes from those who can afford it (he’ll hand the money back if he finds out otherwise). His Achilles heel is the flirtatiously ruthless Tonia Maria (Dorothy Burgess), a vivacious sexpot who merrily cheats on him left, right and centre. She’s also quite happy to sell him out if she can get her hands on that generous reward money offered by Sergeant Mickey Dunn (Edmund Lowe) – who soon falls for her charms as well.

In Old Arizona was the first Talkie Western – and it stands out from other early Talkies that it’s not set in rigid sets with bolted down cameras, but on location. Imagine the excitement of audiences sitting down to watch a scene in a bustling market, to actually hear the sounds of a church bell ringing (it’s showpiece opening), carriage wheels, passengers bickering and Mariachi bands playing, while the camera tracks through the scene. Of course, much of this was accomplished via synchronised sound, applied after shooting – most of the dialogue scenes are shot with a far more rigid style – but it was still gripping. Never again in film history, would a shot of bacon sizzling (audibly) in a pan attract as much comment as it did with the reviewers of this film.

Other parts of In Old Arizona teeter between sound and silence. As mentioned, when the dialogue kicks in the film falls back on theatrical-front-row framing. All three of the principles – the only actors billed – give performances leaning into the principles of silent acting, with the framing and make-up frequently giving added prominence to their eyes (the main form of communication in silent cinema). Dorothy Burgess, in particular, makes her film debut but finds all her prepared awkward theatrical poses to communicate emotion look increasingly out-of-date (much as she’s clearly enjoying playing this ruthless, faithless schemer).

She’s not alone in this. Warner Baxter lifted one of the first Best Actor Oscars and it’s an entertaining performance, full of swaggering, alpha-male cheek. Baxter makes the Cisco Kid somewhere between a scheming rogue and a Robin Hood. But he also strikes a pose a little too frequently and tends to over accentuate gestures and reactions, a clear hangover of his silent career. He does, however, dance through the dialogue with a rolling Spanish accent, and if the character ends in a slightly awkward territory between camp and ruthless, it’s not really his fault so much as the script. He’s certainly far more entertaining than the wooden Lowe, whose voice is flat and uninteresting.

In Old Arizona quickly turns into two shaggy dog stories, stretched out over about 90 minutes. It’s surprising how little plot there is: it could easily have zipped by in 60 minutes. The first act covers the Cisco Kid’s hold-up of a stagecoach and the aftermath; the second an unwitting game of cat-and-mouse where Dunn is at a serious disadvantage as he has no idea what the Cisco Kid looks like; the third the mutual seduction of Dunn and Maria, their attempt to kill the Cisco Kid for his ‘dead-or-alive’ ransom and the Cisco Kid’s ruthless foiling of their scheme. Each feels like a short story, joined together, so it’s not surprising to find it’s adapted from exactly that from O Henry.

By all accounts O Henry’s Cisco Kid was a far more violent and brutal character than Baxter’s jolly, tuneful, gadabout. Sure, the Cisco Kid can handle himself – there’s a fine little action sequence, where he plays possum to gun down three would-be ransom collectors – but by and large he’s a romantic, and it’s clear he’s genuinely in love with the shallow and unfaithful Maria. This feels like it’s been designed to make her betrayal carry some bite, but since she is so blatantly unfaithful it actually makes the Kid look rather dim and slow on the uptake.

Maria is interesting as a Pre-Code character nakedly open in her sexuality – it’s pretty apparent she’s, at-best, a good time girl. She very smoothly seduces the straight-as-an-arrow Dunn (who up until meeting her, makes a big thing of constantly checking his treasured photo of him and his sweetheart). Dunn is of course not the smartest tool – the Cisco Kid runs rings around him during their first meeting, deftly picking him clean of information while not only giving him no idea who he is, but also making Dunn rather enjoy the company of the man he’s meant to be hunting.

It leads into what feels today a troubling conclusion to In Old Arizona. Primed from so-many Westerns that followed, we expect a gun-on-gun ending between the rivals from opposite ends of the law (and, the film eventually suggests, opposite ends of the moral spectrum – the Kid is loyal and decent, Dunn a hypocritic and treacherous). Instead, it becomes more about the Cisco Kid’s deliberately deadly punishment of a woman who has wronged him. It’s hard not to feel that, selfish as Maria is, she doesn’t quite deserve the fate she meets – or the Cisco Kid’s triumphantly heartless Bondian one-liner afterwards.

It’s an uncomfortable ending to a film that in some areas pushes forward the world of commercial film-making (it’s hard not to credit Walsh for the film’s pacier, on-location sequences with their pre-Fordian landscapes, galloping horses and gun-toting action) but in others still has an awkward foot in both silent cinema and the clumsy world of the early Talkies. There are proto-Western ideas here – the sort of narrative ideas that the likes of Ford and Hawks would later finetune and master – but it feels a little too much like a historical curiosity today.