Belated sequel successfully compliments gore with thoughtfulness and surprising sensitivity

Director: Danny Boyle

Cast: Alfie Williams (Spike), Jodie Comer (Isla), Aaron Taylor-Johnson (Jamie), Ralph Fiennes (Dr Kelson), Edvin Ryding (Erik), Chi Lewis-Parry (Samson), Christopher Fulford (Sam), Amy Cameron (Rose), Stella Gonet (Jenny), Jack O’Connell (Jimmy)

Following on not quite 28 years since the original (23 Years Later wouldn’t have had the same ring to it), 28 Years Later sees Danny Boyle return to the post-apocalyptic hell-scape that is a Britain over-run by rage-infected, super-fast, permanently-furious, adrenaline-filled humans (don’t call them zombies!). But those expecting a visceral, gut-punch of blood-soaked violence may be in for a surprise. 28 Years Later is a quieter, more thoughtful film, where the battlefield is for the sort of values to embrace in a world gone to hell.

After a viciously terrifying opening set on the day of the original outbreak – in which vicar’s son Jimmy flees, terrified, from his home after a gang of infected literally rip-apart or infect his family sand terrified telly-tubby-watching friends – we flash-forward decades. Britain is now quarantined and nature has reclaimed large chunks of the land. The few remaining survivors live in protected communities, like a group on Lindisfarne, protected by a causeway flooded at high tide. In the community, 12-year-old Spike (Alfie Williams), is taken to the mainland by his father Jamie (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) to claim his first infected kill, while his confused and ill mother Isla (Jodie Comer) sits at home. But Spike will learn things about himself and his father on the mainland – enough for him to decide to risk taking his mother to meet with the mysterious Dr Kelson (a magnetically eccentric and softly-spoken Ralph Fiennes, in a performance that defies all expectations), who lives in isolation and may just know how to cure her.

Boyle’s film is kinetic and vicious at points, but also has a magnetic beauty as his camera flows across a world in some-ways unchanged from 2002 and in others utterly alien. Scavenged supplies are full of technology from the earlier noughties. The remains of things like Happy Eater restaurants are everywhere, and (proving not everything is bad) the Sycamore Gap tree remains standing. Buildings and villages are overgrown with plant-life and trees. Colossal herds of deer – enough to shake the earth – roam the countryside. In many ways the future is once more the green and pleasant land, with the Lindisfarne community sharing supplies and relearning skills like farming and archery (echoing the days of Henry V, with Boyle calling back to this with a series of shots from OIivier’s film, it’s a compulsory skill as the safest way to kill infected).

There is no chance of salvation or change here. That’s made very clear to us, with the Act Two arrival of Edvin Ryding’s scared Swedish soldier who tells us plainly that being stranded on the island is a death sentence. The world has left Britian behind and they way Erik describes it, all iPhones and Amazon deliveries, is as familiar to us as it is utterly incomprehensible to young Spike. This is not a film about fixing, averting or liberating the island. It’s a film about existing in a permanent state where mankind is no longer the apex predator.

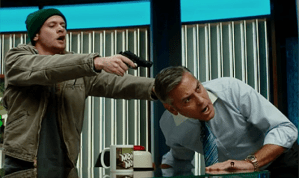

Boyle’s film, with an excellent and thoughtful script by Alex Garland, is therefore all about defying expectation. Spike’s journey with his father is less about a terrifying chase from hordes of infected (though there is plenty of that), or him hardening himself in a brutal world. Instead, it’s about Spike’s nagging doubts about his father being confirmed. Aaron Taylor-Johnson is a very good as a man who is brave and protective, but morally weak and desperate for approval. He’s the sort of man who harangues his son into executing restrained infected (even children) and takes every opportunity in between dutiful caring for his wife, to slip off to his girlfriend. A man who brags on their return as if his son was some sort of Hercules, when Spike knew he spent most of his time missing with his arrows and in a constant state of terror.

28 Years Later captures that sinking feeling children can have when they realise beyond doubt that their parents aren’t perfect. Alfie Williams is excellent as a caring boy, who doesn’t see sensitivity and humanity as weaknesses in the way you suspect his father does. Who sees through his father’s need to promote himself and is disgusted by it. And finds himself drawn closer to his sick mother (a carefully vulnerable performance from Jodie Comer) and finding he has more affinity for a world that still has a place in it for decency, where going back to help someone is not written off as foolishness.

It’s a film that raises fascinating questions about the infected themselves. While millions of infected passed away – their rage filled minds unable to carry out basic tasks like eating or drinking – the small percentage who survived, seemed to retain enough of themselves to maintain some sort of life. They move in herds – or, as some of the obese ground-crawlers do, in a bizarre family unit – and they even have leaders. ‘Alphas’ – those who the disease caused to grow to humongous proportions (in every organ) – direct their charges. And they have intelligence: our main Alpha ‘Samson’ enraged at the death of his comrades, holds back from an attack until the moment is right, mourns the loss of a female infected and maintains a relentless pursuit for reasons we’d recognise from thousands of movies.

28 Years Later uses this to force us to ask questions about ourselves and when human life ceases to matter. To Jamie, the infected have ceased to be human and killing them a duty. But Spike is forced to start to ask: what right do we have to decide there are less human than us, these people who were like us perhaps moments before? Beyond self-defence, is killing them as noble as all that? 28 Days and Weeks Later featured the instant slaughter of anyone with even a suspicion of infection. Years questions this like never before. Everyone on this island is a victim, and the infected deserve just as much memoralizing as victims as the uninfected.

It makes for a surprisingly quiet and meditative drama – even if it is punctuated by moments of shocking blood and gore, from heads and spinal cords being ripped out to a blood-spatted TellyTubbies screening in a vicarage – and one that demands you think almost more than it demands you be thrilled. With exceptional performances, especially from Alfie Williams, it’s a different but mature sequel that redefines aspects of the series. And, based on its jaw-droppingly bizarre ending, its sequel will only take this thinking further.