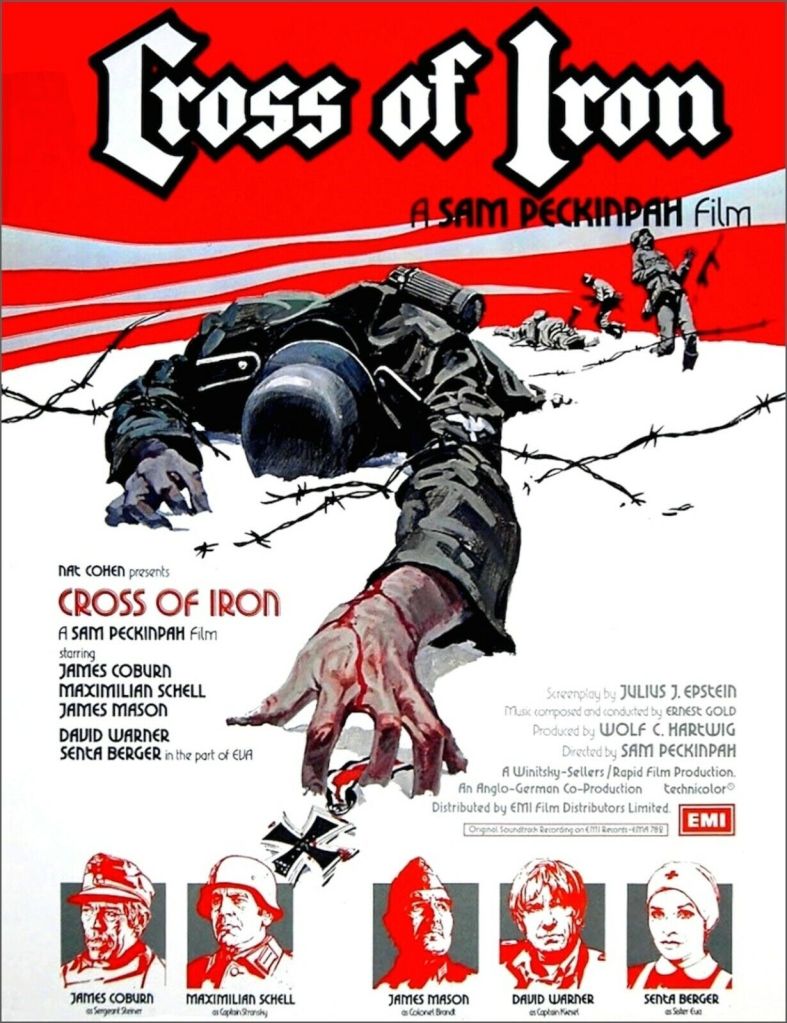

Grim war film, full of blood and horror, but lacking the depth it needs to really make an impact

Director: Sam Peckinpah

Cast: James Coburn (Sergeant Rolf Steiner), Maximilian Schell (Captain Stransky), James Mason (Colonel Brandt), David Warner (Captain Kiesel), Klaus Löwitsch (Krüger), Vadim Glowna (Kern), Roger Fritz (Lt Triebig), Dieter Schidor (Anselm), Burkhard Driest (Maag), Fred Stillkrauth (Reisenauer), Michael Nowka (Dietz), Arthur Brauss (Zoll), Senta Berger (Eva)

If War is Hell, it makes sense that Sam Peckinpah eventually bought it to the screen. Cross of Iron is, perhaps surprisingly, his only war film. But, in a sense, Peckinpah’s grim explorations of the brutal realities of violence made all his films war films. And what better setting for his grim eye than the gore and guts of World War Two’s Eastern Front. If war has any rules they fell silent in this hellish clash where no quarter was given and no decency could be found.

Sgt Steiner (James Coburn) knows this. A grizzled soldier, who despises war, Nazism and officers, he fights through the horrors of the front to protect his men. As the Wehrmacht flees, crushed by the late 1943 advance of the Russian army, the only hope is the vain chance of staying alive. But Steiner’s new commander, Captain Stransky (Maximilian Schell) has other ideas: a Prussian elitest, he’s here for an Iron Cross and the fact he’s inept, cowardly and inexperienced isn’t going to stop him. The clash between Steiner and Stransky will leave a trail of futile bodies in its wake.

Cross of Iron may well just be the grimmest war film this side of Come and See. Shot on location in Yugoslavia, Peckinpah films the Eastern Front as a muddy, chaotic mess where no one seems to have the faintest clue why they are there or where they are going. Soldiers huddle in shallow trenches, officers sit in dusty, crumbling bunkers, the sound of machine guns and the explosion of artillery forms a constant backdrop. Battles are smoky, horrific events with bullets flying, ripping through bodies that explode in squippy mess. Bodies are strewn across the battlefield. Even in the progress to the front lines, tanks absent-mindedly roll over bodies left ground into the muddy dirt.

Peckinpah brings his unique eye for violence to bear. Violence frequently takes place in slow motion, bodies twisting and turning in a crazed dance that seems to go on forever as bullets rip through them. The camera never flinches from the blood of war and the films throws us right into the middle of brutal firefights, tracking through smoky, muddied fields full of bodies. The soundtrack is punctuated by distant artillery gun fire. There is no heroism and the sole focus is staying alive. The soldiers have no interest in politics, no passion at all for the war – only one of them, the smartest dressed, is a Nazi. It’s simply something they vainly hope to survive to see the end of. Even the grizzled veteran Steiner hates the killing, hates the violence, hates the waste.

It makes us loath even more Maximilian Schell’s puffed-up braggart Stransky, a man born wearing an officer’s uniform but hopelessly ill-suited for it. Under fire at his first attack, Stransky is hopeless, reduced to bluntly stating the obvious (“My phone is ringing!”) and confusedly rambling about attacking, withdrawing and counter-attacking all in the same breath. Schell was born to play Prussian primma donnas like this, and he gives Stransky a real cunning and survival instinct. Despising Nazism – he sees himself as above the crudeness of the party – he’s a born manipulator, skilfully deducing the sexuality of his aide to blackmail him, but also a rigid stickler for the rules unable to comprehend a world where he isn’t on top.

He’s the antithesis of Steiner, who has everything Stransky wants: respect, glory, guts. Coburn is, to be honest, about ten years too old for the role (his age particularly shows during his brief respite in a base hospital, where he has a convenient sexual fling with Santa Berger’s nurse), but he’s perfect for the hard-as-nails humanitarian, who hides under the surface deep trauma at the horror he’s seen. Steiner is the natural leader Stransky wants to be and has the Iron Cross Stransky wants. Worst of all, Steiner doesn’t give a shit about the medal, when it’s the be-all-and-end-all for Stransky.

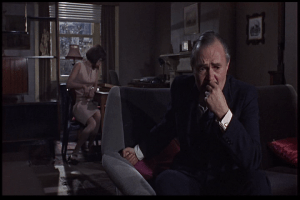

Stransky is so out of step, even the veteran front-line officers think he’s despicable. Colonel Brandt (a world-weary James Mason) scoffs “you can have one of mine” when he hears of Stransky’s dreams while his cynical aide Kiesler (a scruffy, shrewdly arch David Warner) takes every opportunity to show his disgust. Stransky is ignored by the soldiers and is rarely filmed away from his bunker, where he reclines on his bunk like an emperor and avoids any trace of conflict.

So, he knows nothing of the horrors of Steiner’s war. We however do. Cross of Iron opens with a successful raid on a Russian encampment. One of the victims, a young soldier his body torn apart by a mortar, is met with barely a reaction by the soldiers (“We’ve seen worse” says Steiner). Another captured Russian boy is later released by Steiner – and promptly machine-gunned in front of him by advancing Russian soldiers. Caught behind the lines, Steiner’s men are picked off one-by-one despite his desperate efforts to keep them alive.

Cross of Iron went millions over budget – largely due to Peckinpah’s chronic alcoholism (he binge drank every day while shooting and spent days at a time unable to work) – and as a result the ending is abrupt and overly symbolic. (Peckinpah and Coburn had about an hour to cobble it together and shoot it before the filming wrapped up). Peckinpah throws in some clumsy fantasy sequences (especially during Steiner’s fever dreams in hospital) and overly heavy-handed reaction shots from Coburn, overlaid with quick cuts to various horrors or shots of lost friends, which over-stresses the horror of war. Much as Cross of Iron skilfully shows the grimness of conflict, it doesn’t balance this with real thematic weight and depth like, say, The Wild Bunch does.

It’s part of Cross of Iron’s flaws. Under the surface, I’m not sure that Cross of Iron has much more to say, other than war is hell. And with Peckinpah’s work here, there is a sort of satanic, indulgent glee in all that mayhem and slaughter, the bodies riddled by bullets. Peckinpah is a sadistic preacher, the sort of sermoniser who is so keen to tick off the evils of the world, that he doesn’t want to miss a thing. The film feels a little too much at times as a grungy, exploitation flick yearning for art.

But it still has a visceral impact that makes it stand out as grizzled war-film, helped by a granite performance by Coburn, with just enough vulnerability beneath the growls. A tough watch and a flawed film, that lacks the real insight and psychological depth it needs, but with some compelling – and shocking – moments.