Time struggles to heal wounds in Hamaguchi’s meditative, carefully paced and exquisite film

Director: Ryûsuke Hamaguchi

Cast: Hidetoshi Nishijima (Yūsuke Kafuku), Tōko Miura (Misaki Watari), Masaki Okada (Kōji Takatsuki), Reika Kirishima (Oto Kafuku), Park Yoo-rim (Lee Yoo-na), Satoko Abe (Yuhara), Jin Dae-yeon (Gong Yoon-soo), Sonia Yuan (Janice Chang)

They say time heals all wounds: that’s not always the case. It’s certainly something you begin to appreciate in Hamaguchi’s beautiful elaboration of Ozu-style classicism, Drive My Car. Grief and loss do not adjust and correct themselves after the elapse of many months and years. Instead, they can allow pain to fester, ferment and bubble with further questions, regrets, resentments and sorrows. The world becomes a loop, we drive endlessly through, hoping to maintain some semblance of control over ourselves and our feelings.

That echoes the loops through Hiroshima the car of the title drives in this delicate, throught-provoking and mesmerising film, that expands a Murakami short story into three hours of meditative screentime. Yūsuke Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishijima) is a celebrated theatre director, specialising in multi-lingual productions of classic Western plays. One day when his flight is delayed, he returns home unannounced to find his wife, screenwriter Oto (Reika Kirishima), making love to an unseen man. Unnoticed, Kafuku quietly leaves and says nothing. Their relationship seems to continue unchanged for a few weeks, with Oto clearly distressed and concerned when Kafuku is in an accident. But she seems to notice a new reticence in Kafuku and, one day, asks that they have a conversation when he returns home for work. When he does, he finds Oto has died from a sudden brain haemorrhage. What was she going to say to him?

Marking the leisurely pace of Hamaguchi’s film, this takes up the opening 40 minutes at which point the opening credits roll. It’s sprinkled with the details of an elaborate backstory: we discover the couple lost a child aged 5 several years ago and decided to not have another (though Kafuku may regret this). There is a suspicion her lover may have been young actor Takatsuki (Masaki Okada). Two years later, Kafuku agrees to direct a production of Uncle Vanya at a Hiroshima theatre festival. Events there will lead him to confront his conflicted feelings about the loss of his wife he both still adores and also, on some level, resents.

Kafuku has carefully constructed his life to maximise his control. He seems to have abandoned acting his signature role of Vanya. Later in the film Kafuku states that Chekhov’s words reveal our true selves – and its clear, from the snatch we see of his performance shortly after Oto’s death, that true self is one Kafuku is in no position to face. Vanya’s grief, resentment, pain at his lost love, anger at the chances in life he has missed – all of these bring to the surface Kafuku’s feelings about his own life. Hamaguchi’s choice of play is a masterstroke: as we listen to Chekhov’s words they shade and deepen the themes in the film: Chekhov’s autumnal sadness is a perfect reflection of the film.

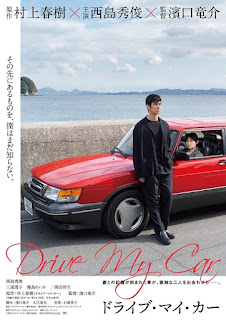

We hear a lot of Uncle Vanya, as Kafuku’s last link to his wife is a cassette recording she made of the dialogue for Kafuku to play in the car (there are gaps for Vanya’s lines, which he fills with a monotonous flatness). He plays this constantly in his car, an aged Saab he has kept beautifully conditioned for fifteen years (meaning he purchased it at the time of his child’s death, adding to its emotional importance). A key part of his sense of control over his life, is the driving and reciting of these lines: hence his request for a hotel an hour’s drive from the theatre.

The isolation and control of driving the car is so important, that it’s a major shock for Kafuku to discover that, for insurance reasons, he has to have a driver for the duration of the production. This is a young woman, Misaki Watari (Tōko Miura), who prides herself on her driving skills (she states it is the only thing she can do well) and who Kafuku reluctantly agrees to hand the keys over to. She wins his eventual trust by her competence and skill – she cares for the car just as he does – and her willingness to sit in silence and let Kafuku continue his ritual of reciting the lines from Vanya.

The growing closeness of these two characters becomes the engine (if you can call it that for a film that luxuriates so much in taking its time) of this thought-provoking and eventually very affecting masterpiece. Both characters find similarities and contrasts in each other: both are dealing with processing the loss of a loved one and, most painfully of all, the questions about who they truly were and what they truly felt that can now never be answered. This plays out in almost the exact opposite of heartfelt conversations: instead long, patient scenes as trust grows not always through words but through mutual comfort, the sharing of a cigarette, discussion of other issues and the impact of time spent in each other’s company.

Time is vital to this. The barriers both these characters have built in themselves to process their feelings would never come down quickly. Hamaguchi’s patience is vital for us to understand how tightly they have wound up their emotions. Kafuku directs with a rigid control, his multi-lingual technique (with at least five languages in the company) demands clarity and long sessions of reading around a table so that actors absorb the flow of the play. It does not allow for flexibility and improvisation. Similarly, Misaki’s driving follows pre-ordained routes and a schedule, that seems to prevent her thinking about other things.

Throughout Hamaguchi avoids sign-posting. Kafuku’s feelings about his wife seem confused and conflicting from scene-to-scene – the Chekov dialogue reflects this, sometimes tinged with intense sorrow and regret, at others bitterness and fury. Kafuku recruits the man he thinks his wife’s lover for the play – casting him in his signature role of Vanya. But why? Does he even know? It could be to accuse him, to control him, to destroy him, to get closer to his wife – or it could be parts of all of them. Definitive answers are kept to a minimum – but then that reflects life.

The relationship between the two comes to a head (such as it is in a film where long conversations slowly reveal buried emotional truth) in a long, late-night car journey shot by Hamaguchi in a carefully controlled one-shot/two-shot that has a classic simplicity that lets the emotion and acting come to the fore. Drive My Car is as unflashy a film as you can get, but its restraint, beautiful but serene imagery and gentle pace add to its slow-burn effect. The moments of emotional catharsis, when they come, are all the more affecting for it – and truly carry a sense of life-changing impact.

The performances are beautiful. Nishijima is quiet, reserved but conveys oceans of conflicted emotion below the surface which he keeps patiently bottled-up. It’s a low-key, highly expressive and tenderly gentle performance. He plays exquisitely with Tōko Miura who at first makes Misaki seem like any number of slightly-surly hirelings, but in turn unveils emotional depths and pain that constantly surprise. Reika Kirishima is both radiant, tender and unknowable as Oto. Masaki Okada is perfect as the lost Takatsuki. Park Yoo-rim is a stand-out among the ensemble as a mute Korean actress communicating through sign language (her acting in the play-within-the-play is stunning).

Originally intended to be filmed in Korea, there is a beautiful serendipity about the pandemic forcing a location change to Hiroshima. No other city on Earth carries such an association with pain and the slow recovery over time. Drive My Car takes the time it needs to explore how grief seeps into us and is only addressed through great care and strength. It’s profoundly engrossing and moving for all of its length – you wouldn’t want to change a thing about it.