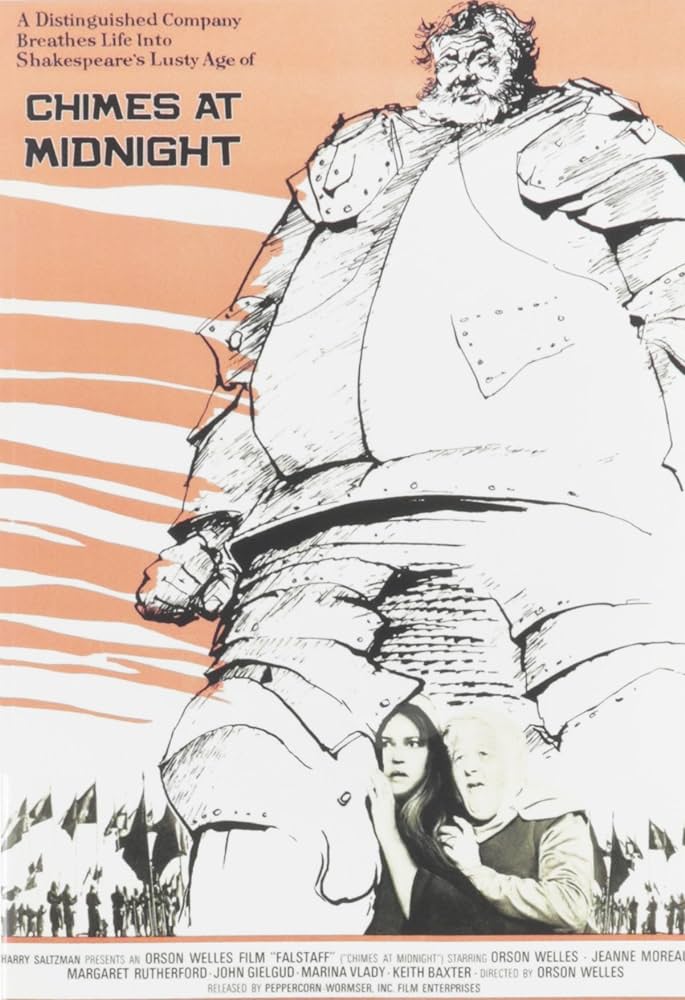

Welles reimagines Shakespeare’s Henry IV as a melancholic tribute to lost glories

Director: Orson Welles

Cast: Orson Welles (Sir John Falstaff), Keith Baxter (Prince Hal), John Gielgud (King Henry IV), Margaret Rutherford (Mistress Quickly), Jeanne Moreau (Doll Tearsheet), Alan Webb (Justice Shallow), Norman Rodway (Henry Percy “Hotspur”), Walter Chiari (Justice Silence), Michael Aldridge (Pistol), Tony Beckley (Poins), Charles Farrell (Bardolph), Patrick Bedford (Nym), José Nieto (Northumberland), Fernando Rey (Worcester), Keith Pyott (Lord Chief Justice), Andrew Faulds (Westmoreland), Mariana Vlady (Lady Percy), Ralph Richardson (Narrator)

For decades Sir John Falstaff was the part Welles couldn’t get out of his head. He’d already made two attempts at re-working the first Henried for the stage, with Age of Kings in the 30s (where Welles played Falstaff in his twenties) and Chimes at Midnight in 60’s Dublin with Welles again as Falstaff and Keith Baxter as Hal in what would be Welles final stage performance. Welles was fascinated with the roistering knight so when he was offered a film of Treasure Island by a Spanish producer, he agreed on condition he could make Chimes at Midnight at the same time with the same cast. Naturally, this being Welles, not a frame of Treasure Island was made, but with Chimes at Midnight he created possibly his most influential Shakespearean work.

Surely, it’s no coincidence the two literary characters Welles felt the closest affinity to was the windmill-tilting wandering fantasist Don Quixote and the mountain of rogueish humour and memories of Golden Years long-gone, Sir John Falstaff. Welles arguably altered the interpretation of the Fat Knight for generations. Before Welles, he was a “Hail Fellow, Well Met” comic, the exuberant force-of-nature Prince Hal must sadly cast aside for the throne. But Welles knew, like few others, what a wasteland missed opportunities, lost glories and achievements-that-never-were lay behind the raconteur. His Falstaff might be cheeky and sometimes jolly, but he’s also a mountain of melancholy, a playboy with no achievements, his glory days long gone. Even without the rejection, there is no future for Falstaff, only hazy memories of a past long gone.

Chimes at Midnight brilliantly repackages, recuts and recombines several Shakespeare plays (not just Henry IV Parts 1 and 2 but also Merry Wives of Windsor, Henry V and touches of Richard II) to reframe this story around Prince Hal and Falstaff and away from both Henry IV and the politics of rebellion (now embodied by Norman Rodway’s bombastic Hotspur). Structure is imaginatively reworked, with Part 2’s recruiting scenes appearing before Part 1’s Battle of Shrewsbury and ingenious touches such as Henry V’s decision to “enlarge that man who railed against our person” retroactively applied to Falstaff rather than a nameless offender.

Welles makes Falstaff a mix of terrible influence and proud parent – no coincidence that a half-smile of pride crosses his face when Hal finally dismisses him. They banter and bounce off each other, but there is a world-weariness. Baxter’s Hal is beginning to focus his mind on the responsibilities that come with the throne. Falstaff alternates between awareness and denial that their salad days are on borrowed time. Strikingly, both of their most prominent soliloquies are overheard by the other. Hal’s secret plans to reform as King is delivered with steely regret by Baxter, while Falstaff stands a short distance behind him; later Falstaff’s mocking of honour in the aftermath of Shrewsbury is impatiently half-listened to by a Hal already starring towards the future. These are two characters who know each other, their flaws and their ruthlessness, more than they might like.

Chimes at Midnight is Welles’ lament not just for Falstaff but for the whole idea of a Merrie England. The film is a set in a wintery land, covered in cold snow and deeply unwelcoming. Mistress Quickly’s inn is a run-down building in farmland, Henry IV’s breath can be seen in his chilly castle, Silence and Falstaff huddle around a flickering fire after a wintery walk. There is a tiredness around the antics of Falstaff’s gang. Falstaff responds to Doll Tearsheet’s attentions with an impossibly weary “I am old Doll, I am old”. We are living in the winter of a whole way of life, which Hal will comprehensively kill off in favour of realpolitik. The days of dreamers like Welles-Falstaff are numbered.

Welles stresses these differences by shooting events in various locations in strikingly different ways. The Boar’s Head Tavern uses more fluidic camera-work, with events frequently happening in multiple plains – characters appear above others on balconies or at the head of stairs – with the action filled with raucous, swiftly choreographed interplay. This contrasts with the Cathedral-like classicism of Henry IV’s court. Where the Boar’s Head is confined and intimate, Henry IV’s medieval palace has towering stone walls, beams of light flowing down from large windows, courtiers still and quiet while Henry effectively speaks to himself, the exact opposite of the boisterous egalitarianism of The Boar’s Head. Justice Shallow’s ramshackle home of bittersweet memories sits somewhere between the two, where the melancholy Falstaff is closest to Henry’s regrets.

Chimes at Midnight is filled with this sort of superb visual language. The film’s centrepiece is a truly impressive set-piece of cinematic flourish, the Battle of Shrewsbury. A masterclass in fast editing, quick cuts and brilliant framing (that makes 200 extras look like a thousand) this scene captures in microcosm the film’s theme of the death of old-fashioned principles. It starts with a knightly charge and degenerates into mud-strewn, brutal hand-to-hand combat with death agonising and swift. You can see the roots here of Saving Private Ryan, with Welles not using cutting, adjusted film stock and montage to create something really visceral and even shocking, as bodies are forced into the mud or cry out in agony – and our fat ‘hero’ trembles and hides to avoid the barbarity.

This is certainly Welles’ finest acting performance in his Shakespeare films. While always a more limited actor than remembered (a combination of laziness and stage fight), Welles was born for this role. His Falstaff builds off an element of self-portrait: a man still capable of lighting up a room with humour (as seen in his delightful ‘mock trial’ of Hal) but who knows he has achieved only a fraction of what might have been (never before have references to Falstaff’s past glories felt more sad) and that only the march towards death awaits. No wonder Keith Baxter’s excellent Hal, clinging to the last chance to let his hair down, is torn somewhere between love, pity and good-natured contempt for this man. The interplay between the two is perfectly pitched.

Chimes at Midnight is filled with rich performances. It may also be Gielgud’s finest Shakespeare performance on film, his rich, fruity tones turning monologues into musings on self-doubt and regret, distancing the coldly austere king even more from the boisterous knight. (That voice is also a gift for the other actors: Welles, Baxter and Rodway all showcase impersonations of Gielgud’s distinctive voice.) This Henry is so full of doubt, bordering on contempt, for his son he may even believe Falstaff’s claims to be the true killer of Hotspur. Rutherford is wonderful as Quickly, earthy and caring; Rodway, from charging across the battle to impulsively springing out of his bath to meet a messenger clutching only a towel makes a superb contrast with Baxter’s calculating prince. Webb’s disappointed Shallow and Moreau’s kindly Doll also make an impact.

Chimes at Midnight’s main impact though is to reimagine these plays in a highly influential way – just look at the BBC’s more recent The Hollow Crown where the Henry IV productions are so indebted to Chimes it might as well be a remake, while Branagh’s Henry V is virtually a tonal sequel. Rarely again would these be plays seen as near-comedies with a sad-but-necessary final act. Instead, they became sadness-tinged meditations of lost chances and missed opportunities, with productions set not in Olivier-style pageantry, but Wellesian chill.

It’s a film tinged with melancholy, so it’s also fitting that as well as a swansong for a lost time, a “Merrie England” past where everything was possible and the future was golden, it’s also the last narrative film completed by Welles (all others would be either documentaries or filmed lectures). When Falstaff, thanked but coldly dispatched, exits clinging to the fantasy of a glorious return but heading towards death, it’s hard not to see Welles himself shuffling away, never again to persuade a young prince (or film producer) to give him a chance again. It’s a moving metatextual ending to a film that reinvents Shakespeare and expertly exploits the tools of cinema.