Clumsy adaptation that presents theatrical invention with the heavy-hand of realism

Director: Sidney Lumet

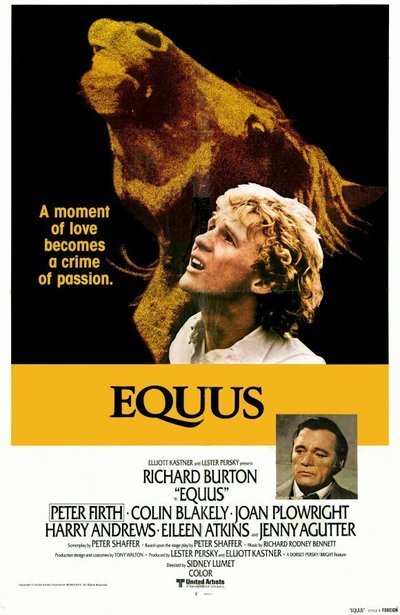

Cast: Richard Burton (Dr Martin Dysart), Peter Firth (Alan Strang), Colin Blakely (Frank Strang), Joan Plowright (Dora Strang), Harry Andrews (Harry Dalton), Eileen Atkins (Hesther Saloman), Jenny Agutter (Jill Mason)

In a parallel universe somewhere, there is a film version of Equus that doesn’t have a single horse in it. It’s probably a better version than this. Peter Shaffer’s stage play was a sensation in the 1970s in the West End and on Broadway – but Lumet’s film robs it of the mystique that made it work, by introducing a (literally) brutal realism. This helps reduce the play into being a quite self-important piece of cod-psychology, with ideas that increasingly seem more simplistic the longer the play lasts.

Dr Martin Dysart (Richard Burton) is a depressed and discontented child psychologist, who is struggling with a general sense of ennui, not sure what is life is for and stuck in a loveless, functional marriage. These feelings grow in him, as he begins to work on the case of Alan Strang (Peter Firth), a troubled young man who blinded an entire staple of horses in a seemingly random act of brutality. What were the deep-rooted psychological problems that caused Alan to carry out this senseless attack? And, by curing it, will Dysart remove from Alan anything that makes him unique?

Shaffer’s stage play used a combination of impressionistic moments, and mime artists, to create the impression of the horses that dominate the imagination (and desires) of Strang. Moments of horse riding (or eventual blinding) were presented symbolically. Meanwhile, Dysart functions as a quasi-narrator, delivering long speeches to the audience on the case, it’s causes and (increasingly) his own feelings of inadequacy and emptiness. It’s a tightrope, that manages to prevent the at-times portentous dialogue and student psychology from seeing either too self-important or slight. Lumet loses this mesmeric suggestiveness, doubling down on its pomposity. It makes for a bit of a mess.

I can totally see why, on film, it was felt necessary to go for real horses. However, it just plain doesn’t quite work. Watching a nude Peter Firth hug, stroke and eventually ride a horse until he reaches an orgasm mid-canter, might have had a sort of magic acted out on stage with dumb-show, puppets and actors as horses. On film, it’s tiresome and suddenly way too much. That’s as nothing compared to the decision to stage the blinding of the horses at the film’s end by showing us in graphic detail a sickle plunging into the eyes of alarmingly real-looking horses, blood pouring across Firth’s face. As that’s (pretty much) the last impression left on the audience for the film, rather than swept up in symbolism you’ll feel grossed out by the graphic violence. It’s not good for the play.

In fact, overlong and too full of speeches and not enough scenes, you watch this and start to wonder if Equus was much cop in any case. Certainly, the way it’s staged here doesn’t work. When Shaffer worked with Milos Forman on Amadeus that play was radically re-worked, extended and remodelled into an actual film that shared lines and DNA with the play, but was a very different beast. Equus is basically pretty close to an exact filming of the stage script, except on location. The show-stopping speeches by Dysart – brilliantly delivered by Burton as they are – come across heavy-handed, portentous and (in the end) off-putting and alienating.

That’s to mention nothing about the plays take on sex and psychology which feels very tired. Needless to say, Strang’s problem is rooted in his relationship with his parents (they fuck you up, you know). His mother (played with wound-up tension by Joan Plowright) is a holier-than-thou type who thinks sex is something a little dirty, while his father (an equally buttoned-up Colin Blakely) is a deeply repressed man who thinks sex is something to be ashamed off. Bound that up with the parents clashes about religion and you wind up with a boy who sublimates his sexual feeling into a confused horse worship, laced with religious overtones.

Which all sounded more daring then than perhaps it does now. Now this sort of sexual confusion (various theories suggest that the young Colin felt his first ever sexual longings after sharing a ride on a horse with a young man and – ashamed of these homosexual yearnings – transferred the association with sex from the man to the horse) was familiar then – it’s pretty much the first thing we look for now. And the insights the play offers around this, don’t carry nearly enough impact or insight to make you feel you are learning something. Anger, frustration, impotence, fear and shame all rear their heads as expected.

Saying that, Peter Firth – who originated the role at both the National and on Broadway – is excellent as Strang. It’s a full-bloodied, committed performance – but also one that is packed with an acute empathy and insight, a sensitive empathy and vulnerability that makes Strang deeply sympathetic even when he is at his most odd.

Richard Burton – who lost his final Oscar bid with this film – is also very good as Dysart. The rich Burton voice is perfectly used for Dysart’s monologues (all filmed in one day, in consecutive order, by Lumet). Burton’s puffy, unhealthy face also matches up perfectly with the sadness and resignation in Dysart – qualities that Burton again brilliantly conveys, his eyes brimming with regrets and his voice catching behind it oceans of confusion, sorrows and self-accusation. It’s one of Burton’s greatest performances, the ideas and elaborate language being a gift for an actor like him who worked best when challenged with complex material.

Unfortunately, the play itself is bogged down in a grimy, unattractive literalism that grinds the life out of it and ends up making it look very slight (this isn’t helped by its huge length). While the acting is very good – Jenny Agutter is also excellent as a young woman whose attempted seduction of Strang triggers a breakdown – the direction is leaden and the play ends up feeling histrionic and simplistic rather than engrossing and insightful.