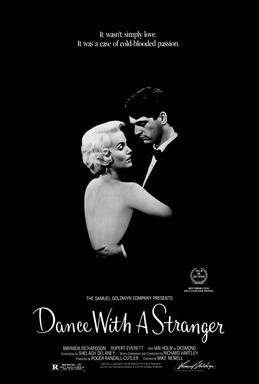

Hell is other people in this Satresque version of the life of Ruth Ellis

Director: Mike Newell

Cast: Miranda Richardson (Ruth Ellis), Rupert Everett (David Blakely), Ian Holm (Desmond Cussen), Stratford Johns (Morrie Conley), Joanne Whalley (Christine), Tom Chadbon (Antony Findlater), Jane Bertish (Carole Findlater), David Troughton (Cliff Davis)

Hell is other people. Dance with a Stranger is the tragic story of how Ruth Ellis (Miranda Richardson in an electrifying screen debut) became the last woman hung for murder in Britain. But it’s also a terrible Satre-like tale of three people stuck a destructive cycle, loathing each other but unable to imagine their lives apart. Ellis is fanatically, obsessively in love with feckless David Blakely (Rupert Everett) who blows hot and cold on her and is nowhere near consistent in his feelings as middle-aged Desmond Cussen (Ian Holm), so besotted with Ruth (who treats him like a benevolent uncle) that he drives her to her assignations and pays rent on the apartment where she sleeps with Blakely.

All three cause each other immeasurable harm in Newell’s cool, bleak, well-made true-crime story that is far less interested in the moments of violence and retribution, than the sad and sorry cycle that leads to them. Tellingly, we never see a single moment of the trial or punishment of Ruth and the film effectively concludes in long-shot as we watch the fatal shooting of Blakely from afar. But who needs the close-up of this inevitable ending, when we’ve had front row seats to the catastrophic relationships that led up to it.

Like many British films, it’s at least partly about class. In 1950s London, we’re still on the cusp of the sort of cultural levelling out of the 1960s. This is a post-war, Agatha-Christie-like London. Blakely and his friends are Waughish Bright Young Things, living on Trust Funds and driving racing cars for fun. Their evenings are spent in drinking clubs aiming for glamour, staffed by those yearning to jump up a notch on the ladder like Ruth Ellis. Such women are of course for dalliances (and casual screws) not for marrying. Ruth’s back-up lover Desmond is an RAF-veteran who misses the war, an overgrown besotted schoolboy and middle-aged bachelor who accepts he is only worth other men’s cast offs.

Blakely’s friends encourage him to mess Ruth around because she’s a working-class strumpet. Ruth is at least partly willing to forgive him because marriage could lift her once and for all out of the working classes. Desmond is of less-interest, because a loveless middle-class marriage of sexual duty simply isn’t as attractive. Neither does Ruth love – or lust after – him the way she does the dynamic, sexy, little-boy-lost Blakely. A man she finds herself so uncontrollably drawn to that, no matter what he does – not turn up, mock her in front of his friends, push her down the stairs or punch her in the face in public – she comes crawling back. Often with Desmond in helpless tow, ignoring his adoration while demanding he drive her to another confrontation with the selfish Blakely.

Dance with a Stranger finds intense sympathy, to various degrees, with all three of its leads. But most strongly it turns Ruth Ellis, who could be a historical statistic, into a figure of real tragedy. Richardson is superb as a woman who is confident, assertive – even arrogantly dismissive – in so many areas of her life except one: her compulsive, obsessive and destructive love for Blakely. Dance with a Stranger charts effectively her mental collapse: from a woman who flirts confidently in a bar, to a quivering, weeping mess standing in the streets staring up at her lover’s window, screaming abuse, smashing up cars and babbling incoherently and inconsolably.

The film charts the same deadly cycle, showing Blakely’s ill-treatment and selfishness having ever more deadly impact on Ruth’s mental well-being. In it all, Blakely isn’t always malicious, more immature and easily led. Everett’s performance is perfect at capturing this playboy uneasiness under a fundamentally weak personality, a man who has been handed everything on a plate and is unable to respond in any adult way to Ruth’s love for him. Nevertheless, his stroppy behaviour gets her fired from her job and his behaviour fluctuates from gifts of framed pictures and promises of devotion, alternated with angry outbursts and emotional and physical violence.

And Desmond Cussen picks up the pieces time and again. Ian Holm is wonderful as this hen-pecked sadomasochist, impotent and all-too willing to debase himself, hurt time and again by seeing Ruth returning time and again to the dismissive Blakely. Holm makes Cussen small, weak, moody and frequently pathetic. He limply follows where she leads and suffers with weary, besotted patience every one of her preoccupied complaints against Blakely. This is man who almost sado-masochistically puts himself in painful situations, can’t be angry with Ruth for more than a few minutes and gets into impotent scuffles with Blakely outside pubs.

But it’s also Cussen who has the gun – and the film at least suggests the possibility that his openness about its location might well have been a factor in Ruth’s later decision to use it. The killing is, deliberately, the least interesting part of the film. What matters is the mental state that led Ruth to this killing. The self-delusion and desperation to believe that she could form a relationship with Blakely, the same obsessive blind-spot that leads to her closing the film writing a condolence letter to Blakely’s mother. Ruth is a victim here as much as him (perhaps more?) a mis-used woman who cannot give Cussen what he wants and can never get what she needs from Blakely.

Newell’s direction is sharp and sensitive and while the film’s cycle of destructive behaviour – Blakely and Ruth row, break-up, Cussen picks up some pieces, rince and repeat – can become overwhelming, it is partly the intention. And it cements the feeling for the audience of being as much trapped in this hell as everyone else. Holm is superb, Everett perfectly cast but Richardson is mesmeric as Ruth, vivid, vibrant, vivacious, vulnerable and victimised in a film that goes a long way to humanise the suffering behind what seem open-and-shut cases.