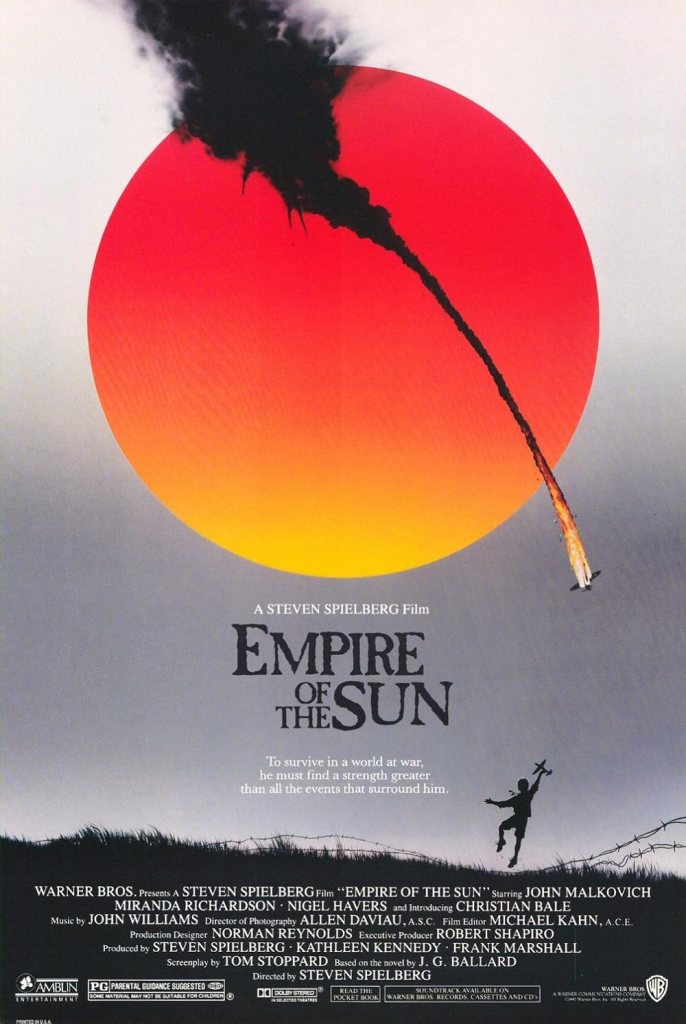

Beautifully shot version of Ballard’s semi-biographical novel with a superb lead performance

Director: Steven Spielberg

Cast: Christian Bale (Jim Graham), John Malkovich (Basie), Miranda Richardson (Mrs Victor), Nigel Havers (Dr Rawlins), Joe Pantoliano (Frank Demarest), Leslie Phillips (Mr Maxton), Masatō Ibu (Sergeant Nagata), Robert Stephens (Mr Lockwood), Takatarō Kataoka (Young pilot), Emily Richard (Mary Graham), Rupert Friend (John Graham), Ben Stiller (Dainty), Paul McGann (Lt Price)

JG Ballard was 12 when he was sent from Shanghai to a Japanese internment camp in 1943 for the remainder of the Second World War. His experiences formed the basis for his novel, Empire of the Sun. The key difference being that, unlike him, young Jim Graham (an incredible Christian Bale) is separated from his parents, falling under the duelling influences of charmingly callous grifter Basie (John Malkovich) and compassionate Dr Rawlins (a very good Nigel Havers), switching between starving trauma and boyish excitement at the explosions of war around him.

Empire of the Sun was originally due to be a David Lean project, before he handed the reins to producer Steven Spielberg. Keen to echo one of his idol’s works – keen to make a film that could sit alongside The Bridge on the River Kwai – and clutching an excellent Tom Stoppard adaptation, Empire of the Sun becomes a grand epic, gorgeously filmed by Allen Daviau. But it also a strangely under-energised affair. It has flashes of powerful emotion, moments where it is profoundly sad and moving. But it’s also an overlong film that struggles to fully commit to a young boy’s emotionally confused reaction to war.

On its release, Empire of the Sun suffered in comparison to Hope and Glory. Unlike Spielberg, John Boorman’s presented a deeply personal, autobiographical view of war through his own memories. Boorman, remembering his own experiences, was not afraid to present war as a child might see it: the grandest game in the world. It’s something Empire of the Sun struggles to process, awkwardly struggling to fuse Jim’s romantic view of the camp as a home full of adventure and its neighbouring airstrip being lined with fighter planes he worships, with his understanding that the guards are dangerous temperamental bullies prone to violence. There is something in this difficult to manage balance between childish wide-eyed excitement and terror at war that Spielberg can’t quite master.

Which isn’t to say there’s not a lot to admire in Empire of the Sun. Visually it’s a wonder, from its early green fields and blue-sky framed shots of the Shanghai British community to the increasingly yellow-filtered bleakness of the punishing, drought packed prison camp and death march that is the eventual fate of the internees. If anything, the film is a little too strong on the desolate beauty of the POW camp, the grand visuals sometimes making an awkward fit with its tale of childhood trauma. John William’s overly grand score – too reminiscent of the adventures of previous Spielberg films – also doesn’t quite work, overpowering moments of the film that should feel more subtle.

This visual and aural grandness would work, if Spielberg could commit to Jim’s frequent view of war as a grand game. After all, separated from his parents in Shanghai he cycles anywhere he wants. In the camp, he cosplays as an American pilot and charges around with the breathless energy of a kid at summer camp. To him, an attack on the airfield becomes a glorious fireworks show. Spielberg is more comfortable with the scenes showcasing Jim unquestionable distress (in particular, a teary breakdown over his inability to remember his parent’s faces). It’s a film that wants to be a survivor’s story amongst suffering, but in which the lead spends a great deal of time enjoying his situation.

Empire of the Sun can’t quite wrap its head around Jim’s psychology, never quite willing to commit to the perspective of a naïve child who can’t quite understand the real horror of the situation he’s in, even while death piles up around him. It’s more comfortable with familiar coming-of-age tropes, such as the early stirring of Jim’s sexuality with Miranda Richardson’s alluringly distant Mrs Victor. (Richardson is very good as this society grand dame, fonder of Jim than she admits).

None of this though is to bring into any question the breathtakingly mature performance by future Oscar-winner Christian Bale (Spielberg’s greatest directorial feat is the unstudied naturalness he helps draw out of Bale). Bale’s performance does a lot to square the circle of Jim’s excitement with the fragile trauma under the surface, almost more than the film does. If there is one thing Spielberg’s film does get, thanks to Bale, it’s a child’s inexhaustible reboundability. Jim is never quite spoiled by his experiences: shaken yes, but still a kind, imaginative child with a relentless optimism. Bale’s performance is highly nuanced, the flashes of pain and panic very effective, the subtle hardening of his survival instinct very well judged.

Bale’s stunningly mature performance powers one of Empire of the Sun’s strongest themes: Jim’s subconscious quest for substitute parents. Barely able to remember his real parents, Jim looks to other adults to fill the gap, while lacking the maturity to judge who is appropriate and who not (he even allows himself to be ‘renamed’ from Jamie to Jim). This brings out a strong Oliver Twist subplot, with Jim fixing himself onto an amoral American Fagin. John Malkovich gives a serpentine menace to the amoral Basie, the grifter who always comes out on top, demonstrating just enough affection for Jim while never leaving you in doubt he’d eat the boy alive if circumstances called for it.

With so many strengths, it makes it more of a shame Empire of the Sun doesn’t quite click. It’s at least twenty minutes too long, dedicating too much time to larger scale moments which, while impressively staged, distance us from the heart of the movie. It works best with smaller personal moments, even within its epic sequences. The Japanese army marching into Shanghai is masterfully staged, but it’s the terror of Jim as he loses his parents in a surging crowd that carries the real impact. Similarly, Jim watching the A-bomb explode, light flowing across the screen, has a silent power. Some moments capture the changing world in microcosm brilliantly: Jim’s discovery that his parent’s staff are looting his home, has the maid respond to his anger by calmly walking across the room and slapping him. This moment captures the fall of everything Jim has known perfectly.

You wish there was more of these smaller, more intimate moments in Empire of the Sun – just as you wish that the film was more slimmed down, more focused and better able to engage with the complex child’s perspective that could simultaneously love and hate the way. Spielberg’s film despite its many strengths and virtues, isn’t quite willing to do that.