Manhunting takes on a new meaning, in this punchy, influential horror-thriller that launched a whole genre

Director: Ernest B. Schoedsack, Irving Pichel

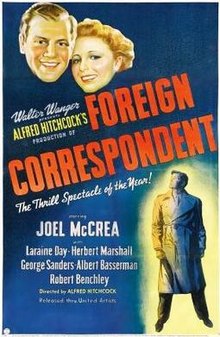

Cast: Joel McCrea (Bob Rainsford), Fay Wray (Eve Trowbridge), Robert Armstrong (Martin Trowbridge), Leslie Banks (Count Zahoff), Noble Johnson (Ivan), Steve Clemente (Tartar), William Davidson (Captain)

It’s man of course. Adapted from Richard Connell’s iconic short story, The Most Dangerous Game sees famous big-game hunter Bob Rainsford (Joel McCrea) washed up on jungle island in the middle of the ocean. He finds a Gothic castle, home to White Russian aristocrat Count Zahoff (Leslie Banks). Zahoff is an overblown egotist with a hunting obsession. He seems an urbane, generous – if sinister – host. But what’s behind that locked iron door? If he’s such a passionate hunter where are all his trophies? And why do people keep getting ship-wrecked and disappearing on his island?

The Most Dangerous Game is staged in a trim 63 minutes, with much of the first half being build-up towards the extended chase sequence that fills it’s second half. The film kickstarted a genre of “manhunt” films, which would take its ideas (and violence) much further. On its release, many of the shots of Zahoff’s human trophy room (with its mounted and pickled heads and his grim, wry commentary of the fates each met on his hunt) were cut, and the first victim, drunken buffoon Martin Trowbridge (Robert Armstrong) is killed off camera. That’s not to say the violence is avoided as the film’s final battle features snapped spines, stabbings and death by bloody-thirsty hounds.

It all makes for an exciting film, told with whipper-sharp pace. This is especially surprising considering how relatively slowly it starts, with Rainsford and his friends chatting about the ethics of hunting (oh the irony!) on their luxury yacht before it sails into Zahoff’s booby trap. Any idea we are in for a staid journey is quickly dispelled as Rainsford’s two fellow survivors are swiftly gutted by sharks, forcing him to swim for shore and the striking, immersive jungle set.

The Most Dangerous Game was shot on the same sets as King Kong – either concurrently or as a test for design work for that classic, depending on who you ask. Schoedsack would go on to direct that – and bring along Wray, Armstrong and several other members of the cast – and TMDG is a wonderful initial try-out for Kong. You can even recognise shots and settings from that film, while the film’s wonderful use of tracking shots, careful editing and superb whip-pans as hunter and hunted charge through the bushes makes for brilliant dramatic tension in its own right.

That’s after we’ve had the odd gothic, horror-tinged oddness of Zahoff’s castle. Zahoff’s trophy room is somewhere between medieval torture chamber (a sort of iron maiden device seems to be the main persuader Zahoff users to get guests to join in ‘the game’) and haunted house, with pickled heads bubbling in jars. The house itself is intimidating, huge in scale with rooms decorated with blood-thirsty hunting tableaus inspired by myths and legends.

It all matches Zahoff’s own OTT grandness. Played, in a remarkable film debut, by Leslie Banks, Zahoff is a truly iconic villain. Banks, a war veteran with striking scars and half of whose face had been paralysed, is a mesmeric, captivating presence whose eyes shine with obsessive indifference and sadistic glee. Spending his nights pontificating to his guests – who he treats with snobby disdain – he’s also a braggart and a cheat. He talks a good game of giving his guests a “fair chance” – but arms them only with a knife, while he has a bow and arrow and rifle (not to mention a team of dogs and three burly, violent, Tartar servants). Banks plays the role to the absolute hilt, dressed in stormtrooper black, a riotous operatic grandness just the right side of camp, relishing every second.

He soaks up most of the interest in the film. Joel McCrea is left with little to do but to look wary – although the revenge-soaked fury he returns with in the film’s violent denouement is effective. Fay Wray adds a lot of charm to the film in this early trial as scream queen. Robert Armstrong tries the nerves a little too much as her drunken brother, overplaying the comic stumbling. But the relative grounded normality of McCrea and Wray is needed for us to stick with them when they are reduced to fleeing through the jungle to escape the maniacal eyes of Banks.

Zahoff of course wants to get the respect of noted hunter Rainsford, but that doesn’t stop him frequently cheating in their battle of wills. He’s smart enough to dodge Rainsford’s traps, but doesn’t hesitate to unleash his hounds or leave (what he believes to be) the killing blow to someone else. It’s a nice beat to remind us that, for all his big speeches, Zahoff is an inadequate bully desperate to be the legend he claims to be.

It’s something we grow aware of throughout the film’s momentum packed second half, essentially a wild chase through the jungle with Rainsford and Eve desperately trying everything to stay one step ahead (the original story didn’t include a female character, but it’s a wonderful insertion which helps humanise Rainsford considerably compared to Zahoff). The unrelenting action, expertly shot, is undeniably exciting (even if we expect, based on its successors, a higher number of innocents being chased to meet fatal deaths) helping to make TMDG one of the most influential B-movies around.