Big bangs and silly action abounds in Nicolas Cage’s enjoyable action epic

Director: Simon West

Cast: Nicolas Cage (Cameron Poe), John Cusack (US Marshal Vince Larkin), John Malkovich (Cyrus ‘The Virus’ Grissom), Steve Buscemi (Garland ‘The Marietta Mangler’ Greene), Ving Rhames (Nathan ‘Diamond Dog’ Jones), Colm Meaney (DEA Agent Duncan Malloy), Mykelti Williamson (Mike ‘Baby-O’ O’Dell), Rachel Ticotin (Guard Sally Bishop), Monica Potter (Tricia Poe), Dave Chappelle (Joe ‘Pinball’ Parker), MC Gainey (‘Swamp Thing’), Danny Trejo (‘Johnny 23’)

A rickety plane full of the worst of the worst and very low security. Battles to the death over the fate of a cuddly bunny. A car dragged after a flying plane. On any other day, that might all be considered strange. In Con Air it’s just grist to the mill. Made in the heart of Cage’s post-Oscar swerve from off-the-wall indie star to pumped-up, eccentric action star, Con Air is loud, brash, makes very little sense, feels like it was all made up on the spur of the moment and is rather good fun.

Cameron Poe (Nicholas Cage) is an Army Ranger who ends up in jail after he is forced to protect himself and his wife (Monica Potter), with deadly consequences, in an unprovoked bar brawl. Seven years later he is finally about to be released from prison to meet his young daughter for the first time. To get him to his release though, he’ll need to hitch a ride on a prison transfer plane that is shuttling the ‘worst of the worst’ to a high security prison. With criminal genius Cyrus ‘The Virus’ Grissom (John Malkovich) and his number two ‘Diamond Dog’ (Ving Rhames) on board, what could go wrong? Needless to say, the criminals seize the plane – can Cameron, with help on the ground from US Marshal Vince Larkin (John Cusack) protect the hostages and save the day?

There isn’t really any way of getting around this. Con Air is a very silly film. Nothing in it really bears thinking about logically. To the tune of a soft rock score and Leann Rimes (actually, How Do I Live is a damn good song, and I won’t hear a word otherwise), Simon West shoots the entire thing like it was a primary-coloured advert for action movies. It’s the sort of film that feels like the action set-pieces were written first – “The plane will crash on the in Las Vegas! Right, how do we get the plane to Las Vegas and out of fuel?” – and where the actors thrash around trying to make a plot that feels made-up on the spot full of try-hard dialogue work.

But despite this, Con Air seems to work. Whether it’s because of its brash confidence in its own ridiculousness or because it hired enough scribes to pen one-liners and character quirks to just about give the film a sense of wit and character (Poe’s ongoing effort to protect the cuddly bunny he intends to give his daughter is just one of a decent set of running gags – “Put the bunny. Back. In the box.”). You suspect watching it that there was the intention somewhere along the line to make something darker and more violent – the criminals’ seizure of the plane is surprisingly bloody – that just got forgotten about when it was decided it worked best as a dumb end-of-term panto.

A large part of its success stems from Cage’s droll performance. Turning himself into a sort of every-day action hero with just the odd trace of his famed grand guignol eccentricity here and there, Cage’s Cameron Poe makes for an intriguing lead for a balls-to-the-wall action film. Poe is softly-spoken, invariably polite, sweetly excited about seeing his daughter and pretty much encounters every unlikely event he sees with a laconic dead-pan (“On any other day that might be considered strange” he murmurs when witnessing the plane drag a sports car behind it through the air).

Cage of course looks ridiculously pumped up and spends most of the film in an obligatory Die Hard style vest. He hands out ruthless beatings of ne’er-do-wells – although only Cage could impale a serial killer on a pipe and sadly intone “Why couldn’t you just put the bunny back in the box”. Only Cage would take a part clearly intended as a Bruce Willis smirker and turn it into a sort of kick-boxing Paddington Bear. His stubborn refusal to take the film seriously means he cancels out Simon West’s ridiculously macho aesthetic that otherwise infects almost every frame. While everything else is loud, sharply cut and features actors spouting try-hard tough dialogue, the film’s central character spends the opening of the film learning Spanish and exchanging surprisingly sweet letters with his daughter and strolls around earnestly trying to do the right thing.

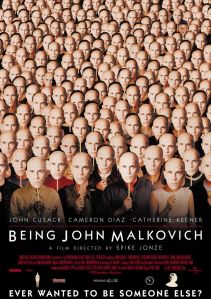

John Cusack similarly runs counter to the tone. Clearly counting the minutes until he can cash his cheque, Cusack turns his US Marshal into a laid-back, sandal-wearing boy scout, quietly exasperated about the wildness around him. I suspect half of Cusack’s drily low-key dialogue was written by him just to keep himself interested. Malkovich is cursed with the film’s worst try-hard tough-guy dialogue, but even he enjoys downplaying the role into softly spoken comedy. The three leads leave the blow-hard silliness to their foils Colm Meaney (as a permanently angry DEA agent) and Ving Rhames (as a violent would-be revolutionary).

With most of the people in it not taking it seriously, it generally means the ridiculousness of the plot – an aimless capture of a plane built around a series of set-pieces – and flashes of violence get watered down in favour of comic nonsense that of course ends with a rammed slot machine hitting a jackpot and the villain being stabbed, launched, electrocuted and crushed in a super-display of overkill. Whether this is what West intended who can say? But it’s certainly a lot better this way.

After all who cares if the villain’s masterplan depends on the sudden appearance of a sandstorm or that no war hero would ever go to jail for protecting his wife in a bar (Poe must have the worst lawyer in the world). It’s all about the jokes (a body at one point has a message scrawled on it and is literally posted into thin air), the bangs and, above all, the weary, half-smirking performances of the leads who can’t believe the nonsense they are sitting in the middle of.