DeMille’s massive, camp epic sets the table for what we expect from Biblical epics

Director: Cecil B. DeMille

Cast: Charlton Heston (Moses), Yul Brynner (Rameses II), Anne Baxter (Nefretiri), Edward G. Robinson (Dathan), Yvonne De Carlo (Sephora), Debra Paget (Lilia), John Derek (Joshua), Cedric Hardwicke (Seti I), Nina Foch (Bithiah), Martha Scott (Yochabel), Judith Anderson (Memnet), Vincent Price (Baka), John Carradine (Aaron), Olive Deering (Miriam), Douglass Dumbrille (Jannes)

“Let my people go!” Close your eyes and think of Moses. Chances are you’ll see an image of Charlton Heston, arms spread wide, parting the waves to lead his people to freedom. Heston had been partly chosen for his resemblance to Michelangelo’s sculpture of the famous law-giver. It’s also a tribute to how Cecil B DeMille’s slightly ponderous, very-very-serious Biblical epic pretty much defined what we expect from Bible stories.

The Ten Commandments would be DeMille’s final movie (and for all its many flaws, it’s way more deserving of the Best Picture Oscar than the valedictory pat-on-the-back his penultimate film got). It’s basically a triumphal capturing of his self-important style, with sonorously devout voiceover and a faultless hero chiselled from marble an excuse to fill the screen with action, campy scheming and lots of sexiness. The Ten Commandments became a massive hit because it’s a rollicking pile of nonsense and something you could persuade yourself was “good for you” because it’s about the Exodus.

It’s a BIG film. DeMille delivers an opening direct-to-camera address, dripping with pompous self-satisfaction, where he piously tells us about the level of historical and Biblical research he’s carried out. The credits list a stack of professors, historians, religious experts and, last of all, the Holy Gospels as sources (presumably the Gospels’ writers got no cut of the vast profits). DeMille, as per his style, marshals thousands of extras and some huge (and distinctly sound-stage looking) sets to play out a series of tableaux, many of them rooted in classic silent-movie framing and techniques. Special effects abound to create plagues (disappointingly the film skips seven of them) and parting of the Red Sea. DeMille narrates with the grandiose aloofness of a Sunday School teacher.

It’s almost enough grandeur to make you overlook this pageantry covers a rather camp, frequently silly piece of entertainment. The film is ripe with buff actors striking poses: Heston does a lot of this during the first half, matched by Brynner (who worked out at length so as not to be shown-up). Opposite them, gorgeous Israelite and Egyptian babes fawn and flirt. The film is at least as interested in the love/hate relationship between Moses and Nefretiri as it is in the Word of God, not least because DeMille knows that this soapy stuff really sells.

Perhaps that’s why Anne Baxter plays Nefretiri with a level of campy purring that would be almost laughable, if you weren’t sure that she’s in on the joke. Relishing the chance to play a sex bomb – in costumes designed to stress her assets – Baxter simpers, flirts, drapes herself across Heston’s ram-rod (in every way but one of course – he’s righteous man of God) Moses and gets to utter lines like “Oh Moses, Moses, you stubborn, splendid adorable fool”. She mocks and cajoles Rameses into rejecting Moses’ demands, partly because she can’t stand Moses is immune to her charms, partly because she can’t bear the idea of Moses leaving Egypt (and her) behind forever.

Ten Commandments elevated Heston to the rank of the immortals. Few actors could carry the weight of films like this as well as he. His performance is in two acts. The first is the visionary, egalitarian adopted son of the Pharoah: the guy who builds the best cities, turns rival kingdoms into allies, gives the stuffy priests’ grain to the slaves (even before he finds out he’s one of them) and whom Seti (a haughtily British Cedric Hardwicke) would rather took over the kingdom than Rameses. Discovering his roots, he morphs over a (long) time into the white-haired, broad-shouldered prophet, speaking most of his lines in sonorous block capitals (“BEHOLD. THE POWER. OF GOD” that sort of thing). Very easy to mock, but only Heston could have played such woodenly written silliness with such skilful conviction.

He generously said he believed Brynner gave the better performance. Brynner does have the more interesting material. A playboy monarch who is true to his word and seems (at first) torn with how he feels about this adopted brother who overshadows him at every turn, Brynner adds a lot of light and shade to a character written as a pretty much straight villain. Moses is presented as such an imperious stick-in-the-mud, it’s a little tricky not to feel a bit sorry for the put-upon, inadequate Rameses, for all he’s a tyrant.

Heston was the only actor who went on location for a few key shots (the others all perform on sound stages or in front of green screens). Keeping things sound stage based allowed DeMille to have complete visual control over the set-ups. This suited his conservative camera movements and editing – most of the scenes take place in a few carefully extended mid-shots, that allow us to soak up the pretty costumes and the theatrical acting. The Ten Commandments is partly a flick-book of devotional pictures – so much so that a tracking shot into Seti’s face when he banishes Moses stands out for the amount of camera movement.

That doesn’t stop DeMille throwing in plenty to look at in frame. With Heston spending half the movie as (in some cases literally) the voice of God, John Derek’s Joshua carries the action torch: chiselled of chest, he’s introduced zip wiring to save Moses’ mother from being crushed by a mighty stone. Like most of the “good” characters he gets very little to actually work with: the decent Jews are either excessively pure or aged men of physical weakness who commentate on the wonders around us. Still, it’s better than the hilariously cheesy dialogue of the regular Israelites (“We’re going to the land of milk and honey – anyone know the way?”) that contrasts laughably with the Biblical pastiche Moses and the other principals speak in.

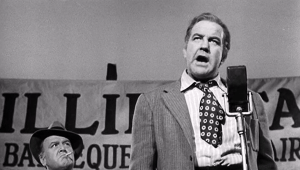

DeMille has plenty of fun with the doubters and naughty among the Israelites. Edward G Robinson goes gloriously over-the-top as quisling Dathan, blackmailing Joshua’s girl Lilia (a timid Debra Paget) into years of servitude and taking every single opportunity to undermine Moses’ leadership. It works as well: no wonder Moses gets so peeved – the slightest set-back and the Israelites seem ready to stone him. Dathan leads the final act Golden Calf orgy (DeMille’s voiceover tuts constantly, while letting us see as much of the action as the censor would allow) while Moses is up the mountain picking up the Word of God.

Robinson has the tone right though: the cast is stuffed full of OTT actors. Vincent Price plays a perverted Egyptian architect with lip-smacking glee. Judith Anderson jumps over the top as Nefretiri’s nursemaid. Nina Foch (one year younger than Heston!) plays Moses’ adopted mother with grandiose gentleness. They know this is a big, silly, pose-striking pantomime passing itself off as a piece of devotional work.

But that’s why its popular. DeMille knows that people don’t want to see a devotional lecture – or even really have to think that much about the rights and wrongs of an Old Testament story that sees the Lord strike down a load of kids with a murderous cloud (even Moses is torn by this for a minute). The Ten Commandments is huge in every sense, full of campy nonsense, pose-striking acting and a mix of stuff it’s taking very-very-seriously and campy ahistorical nonsense. It’s a winning cocktail that doesn’t make for a great film (or even, possibly, a good one) but cemented it as a landmark everyone recognises even if they haven’t seen it. In a way, making it one of Hollywood’s most magic epics.