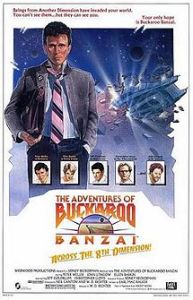

Solid film stuck forever in the shadow of a landmark, all answers and no mystery

Director: Peter Hyams

Cast: Roy Scheider (Heywood Floyd), John Lithgow (Walter Curnow), Helen Mirren (Tanya Kirbuk), Bob Balaban (R. Chandra), Keir Dullea (Dave Bowman), Douglas Rain (HAL 9000), Madolyn Smith (Caroline Floyd), Elya Baskin (Maxim Brailovsky), Dana Elcar (Dimitri Moisevitch), James McEachin (Victor Milson), Natasha Shneider (Irina Yakunina), Vladimir Skomarovsky (Yuri Svetlanov), Mary Jo Deschanel (Betty Fernandez)

2010 is the film 2001 could have been. That’s not really a good thing. Where 2001 was invested with such Kubrickian mystique that is has engrossed and bewitched audiences for decades with its elliptical structure, haunting experience and complete lack of definitive answers or interpretations, 2010 is nothing but answers. Don’t get me wrong: 2001 is a tough act to follow, but 2010 is rather like rolling from looking at a Picasso to checking out a talented local artist. One produces art that you would happily hang on your wall – the other produces a priceless, timeless masterpiece that will define its medium for decades to come.

That’s the thankless position for Peter Hyam’s solid and basically perfectly fine science-fiction. In many ways, without the existence of 2001, it’s sensitive exploration of the deep-space thawing of Cold War relations, exploration of how more unites mankind than divides us, musing on questions of what makes us human would have felt quite hefty. 2010 however, forever in comparison to 2001, feels more like a well-made info dump, dedicated to answering any questions left over. As Heywood Floyd (Roy Schieder) takes part in a joint US-USSR mission to find the Discovery we are painstakingly told what the monoliths are, what they were for, what happened to Dave, why HAL went loco, where mankind goes next… all wrapped around a world teetering on nuclear war and the creation of a new star raced through in under two hours so swiftly that barely a scene goes by without breathless exposition.

It’s fine. Although anyone who sat through 2001 and wanted to know the exact science of the monoliths and the exact reasons for HAL’s psychosis may well have missed the point. Hyams film is a solid, decent, noble attempt to follow-up on a landmark that manages to pay a respect to the original (despite cringe worthy touches like a magazine cover in which Clarke and Kubrick cameo as the faces of the superpowers leaders – one of two wonky Kubrick references alongside Mirren’s character’s barely discussed anagram name) without wrecking its legacy. Dutifully the film replicates a few shots and throws in some already iconic sound cues. But it’s done in a way that manages to lift 2010 with some of the haunting poetry of the original, rather than dragging it down.

There is some decent stuff in 2010 a film swimming in Cold War tensions. The US and USSR crews start with an abrasive suspicion of each other, which refreshingly thaws out in a shared sense of team and there being no borders in space (despite the best efforts of their governments). A big part of this is the warmly-drawn relationship (with more than a touch of the romantic) between John Lithgow’s nervous engineer, on his first mission in space, and Elya Baskin’s deeply endearing experienced cosmonaut who takes him under his wing. More time is allowed to let this grow as a human relationship than any other pairing in the film, and it pays off in capturing on a personal level the film’s hopeful sense that tensions between two nations intent on MAD could thaw.

But the film mostly riffs on the original. The haunting presence of Kier Dullea’s Dave Bowman – now something beyond human – is effectively used at several points (a series of appearances to Roy Scheider’s Floyd inevitably sees Dullea rattle from shot-to-shot through every make-up stage he went through in Kubrick’s haunting conclusion to 2001, as 2010 continues to tug its forelock at its progenitor). The Discovery – now a dust covered relic in space – is fairly well re-created (even if the scale of the model is ludicrously off-beam in several shots featuring space-walking astronauts). Bob Balaban – bizarrely playing an Indian scientist, though thankfully without dubious make-up – has several scenes recreating Dullea’s floating in HAL’s innards, slightly undermined by the fact Balaban looks like he’s uncomfortably hanging upside down.

Tension is drawn from whether HAL himself – once again voiced with brilliantly subtle emotion just under his monotone earnestness by Douglas Rain – will once again flip out, but 2010’s generally hopeful alignment along with its ‘no answer left unturned’ attitude does rather undermine this tension. Just as we are never really left in doubt that Helen Mirren’s no-nonsense commander and Roy Scheider’s guilt-laden Floyd (who has had a character transplant from the coldly inhumane bureaucrat of 2001) will find a way to both respect each other and work together. You can however agree that 2010 does find more room for human feeling and interaction than 2001. Nowhere in that film could you imagine the hero sharing his anxiety about a risky space manoeuvre, huddled with an equally fearful Russian cosmonaut. Or 2001s version of Dave visiting his wife, or any of the characters entering into any sort of discussion on the morality or not of sacrificing HAL.

2010 also has some striking imagery among its cascade of answers and facts, But finally it’s only really a sort of epilogue or footnote to something truly ground-breaking. A curiosity of complete competence, which never really does anything wrong but also never really does anything astounding either. You’ve got to respect Hyams guts in even attempting it (I’m sure plenty of other directors flinched at the idea of recreating Kubrick) but you’ve also got to acknowledge that it falls into the traps of conventionality that 2001 avoided doing. 2010 is, at heart, really like a dozen other films rather than something particularly unique. Unfortunately for it, that was never going to be enough.