Sexist, violent, crude and deeply disgusting. Transformers continues to make you weep for your childhood memories

Director: Michael Bay

Cast: Shia LaBeouf (Sam Witwicky), Josh Duhamel (Colonel William Lennox), John Turturro (Seymour Simmons), Tyrese Gibson (Robert Epps), Rosie Huntington-Whiteley (Carly Spencer), Patrick Dempsey (Dylan Gould), John Malkovich (Bruce Brazos), Frances McDormand (Charlotte Mearing), Kevin Dunn (Ron Witwicky), Julie White (Judy Witwicky), Alan Tudyk (Dutch Gerhardt)

I’m ashamed to say when I saw it in the cinema I sort of enjoyed it. Goes to show how the excitement of a trip out can make the most ghastly, horrible, vile piece of work feel like fun. Even at the time, I recognised enjoying Transformers: Dark of the Moon was like becoming engaged with the story-telling in a porno. Doesn’t change the fact it’s a crude exercise, pandering to your baser instincts.

The plot? Autobots. Decepticons. Blah, blah, blah. Don’t worry if you’ve not seen the previous films: this merrily contradicts them. In the 60s an Autobot ship crashes on the moon, the moon landings were all about exploring the wreckage. In the present day our “hero” Sam (a never more annoying, unlikable Shia LaBeouf) can’t land a job and the Decepticons hatch a plan to destroy the planet by bringing their homeworld Cybertron here. Former Autobot Boss Sentinal Prime betrays everyone. Optimus Prime doubles down on being a psychopath. It’s very loud and makes no sense.

Transformers: Dark of the Moon exposes Michael Bay’s aesthetics as those of a porn director. Everything is crude, huge, brash, obvious, tries to do as much work for you as possible and panders to your worst instincts. Dark of the Moon is shocking in almost every possible sense: from its crude sexism and leering camera, its revoltingly heavy-handed, end-of-the-pier, terminally unfunny comic relief, its overlong, explosive battle sequences (shot with the slavering longing of a pornographic gang-bang). Dark of the Moon is a revolting film, a disgusting perversion of what was a kids cartoon.

Can you imagine letting a child watch this? Let’s deal with its disgusting sexism first. Megan Kelly had been sacked between this and Revenge of the Fallen for denouncing Michael Bay’s working basis (I’ll admit calling him Hitler went too far). Every chance in the film to disparage her character is taken (two appallingly unpleasant tiny Autobots all but call her a bitch). She’s replaced by Rosie Huntington-Whiteley, introduced walking up-stairs, the camera starting at her feet and trailing up, lingering on her bottom (she’s wearing just a slightly-too short shirt). Later two characters will discuss “the perfect curves” of a car – while the camera pans up her body. Those are only the most egregious of the deeply uncomfortable sexual objectification of this poor woman.

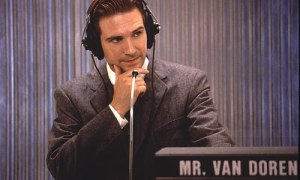

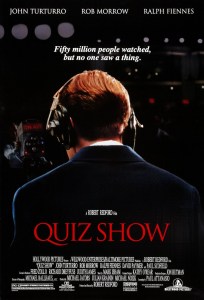

How about its crude humour? Several actors enter a private competition to give the loudest, least funny comic cameo. Malkovich gurns and rants as Sam’s pointless, kung-fu obsessed boss. John Turturro does whatever he wants as a Transformers obsessed former-agent. Kevin Dunn and Julie White are eat-your-fist levels of unfunny as Sam’s parents. Worst of all is Ken Jeung as a Deep Throat style informer whose every scene is crammed with homophobic jokes about anal and oral sex. Remember, once upon a time this was for kids. All this alleged humour does is add to the already bloated run-time. You’ll suffer through every single word, because you certainly won’t miss it due to laughing. Bay’s idea of funny is if the joke is delivered LOUD by a wild-eyed actor, preferably accompanied by a whip-pan. He’d probably love Roy Chubby Brown.

The film has two of the least likable heroes perhaps ever placed on film. Shia LaBeouf must have genuinely hated himself by the time he made this. Perhaps that’s why he makes no effort to make Sam even one per cent likeable. Sam is a whining, petulant man-child, alternating between bitching about his job to bragging about his trophy girlfriend (whom he spends half the film whiningly chasing). In the first of these films, LaBeouf had a goofy charm. Now the character is just a deeply arrogant little prick, with major entitlement issues. LaBeouf shouts and screams throughout, but mostly just looks really angry at himself for even being there.

Then we come to the pièce de resistance: Optimus Prime. When I was a kid, this noble warrior was like the perfect Dad. Traumatised kids wept when he died in the animated movie. Revenge of the Fallen started turning him into a violent killer. This completes the journey. Bay probably thinks Prime is a bad-ass taking names. He’s actually a violent, psychopathic killer who arrives at a battle with the inspiring words “We will kill them all”. Prime allows the whole of Chicago to be destroyed (at the cost of millions of lives) to prove a point to the stupid humans. At the film’s end he reacts to Megatron’s offer of a truce by ripping out his spine and then executes Sentinel Prime by shooting him point blank in the head while Sentinel pleads for his life. Ladies and gentlemen: our hero.

It’s customary to say the special effects are good, so: the special effects are good. The violence is pornographic, shot often in slow-mo, with explosions, fast editing and huge noise filling the screen. Transformer bodies are mauled, beheaded, eviscerated. There are several rather chilling executions. Prime rips out the equivalent of heart, lungs, eyes and brains. Bay adds a reddish oil to the transformers, which looks like blood spraying up. Just like the humour, the action goes on FOREVER. The final Chicago battle takes up fifty minutes of buildings falling, brutal slaughter and triumphalist flag-waving. After repeated viewings it’s not just boring, it starts getting offensive.

Dark of the Moon is, quite simply, only just (only, only, only just) better than Revenge of the Fallen – and it says it all that it’s because it’s not as racist. In every other sense it’s simply revolting: violent, crude, sexist and homophobic. This is a horrible, horrible film made by a soulless director. It genuinely is like a beautifully shot pornographic film that wants you to respect the craft that’s gone into it while you finish yourself off. For a brief few seconds you might get sucked in – but you’ll certainly not be boasting about it afterwards.