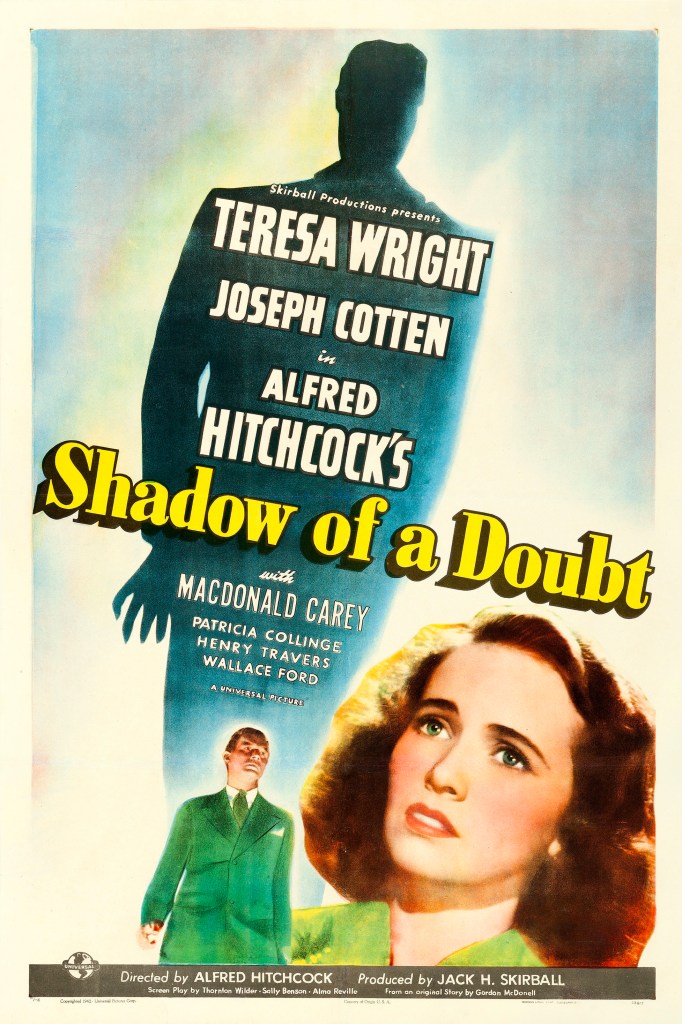

A small town family is corrupted by a malign force in Hitchcock’s favourite of his films

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Cast: Teresa Wright (Charlie Newton), Joseph Cotton (Uncle Charlie Oakley), Macdonald Carey (Detective Jack Graham), Henry Travers (Joseph Newton), Patricia Collinge (Emma Newton), Wallace Ford (Detective Fred Saunders), Hume Cronyn (Herbie Hawkins), Edna May Wonacott (Ann Newton), Charles Bates (Roger Newton)

It’s a surprise to discover Shadow of a Doubt was Hitchcock’s favourite of his films (although the Master of Suspense was a notorious kidder). It rarely makes even the top ten of Great Hitchcock’s and for years was semi-forgotten in his CV. But delve into this small-town chiller and it becomes less of a surprise the master was so fond of it. Hitchcock’s first American-set film (his previous American films being British-set), this takes an idyllic, everyone-knows-your-name, no-doors-locked small town in California and injects into the middle of it a ruthless sociopath, as charming as he is shockingly ruthless. Doesn’t that sound like Hitchcock all over?

That small-town is Santa Rosa in California. There the Newton family is thrilled at the imminent arrival of Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotton) from New York. None more so than his niece Charlie (Teresa Wright), a precocious teenager who shares her uncle’s wit and worldly wisdom. He arrives laden with gifts – but also dragging two police detectives and swirling rumours of terrible crimes. Surely Uncle Charlie – hero to all and idol of his niece – can’t also be the ruthless “Merry Widow” killer, dispatching aged widows for their riches? And, if he is, what on earth will Charlie do about it?

A lot of what would become Hitchcock’s central concerns in his later, darker, mature works make their inaugural appearance in this dark, creeping mystery. Everything in the Newton home is perfect, until they welcome Charlie, whose amiable greed and self-interest tarnishes everything he touches. Despite this, he’s the most likeable, charismatic, charming character in the film. So much so, a big part of us wills him not to be the murderer we can all be pretty confident he is. He’s far too exciting and dynamic for us to want him torn away from us!

The two Charlies are close – so much so Hitchcock would surely have dialled up the incestuous spark between them even further if he had made the film fifteen years later. They have a near supernatural mental bond, seemingly able to predict where and when the other might be. They laugh and flirt. In arguments Uncle Charlie grasps his niece like a frustrated lover, clutching her too him. As well as sharing many character traits (implying it would be easy for Charlie to become like Uncle Charlie) they’re closeness feels as much like a courtship as it does familial closeness. When Uncle Charlie takes Charlie to a gin bar to gain her confidence and support to hide from the cops, the entire scene feels like the appeal of a would-be lover.

It overlaps another theme future Hitchcock have taken further: the thin line between innocence and killer. Uncle Charlie and his namesake have a special bond. They share the same world-view and many of the same ideas. They’re both charismatic and natural leaders. They both feel stifled by this small-town world. They are both ruthlessly determined when roused. One of them might be innocent and one might be good – but how much of a push would it be to turn one into the other?

Hitchcock probes this possibility throughout in a film stuffed with doubles and duality. Both Charlies are introduced with similar shots of them lying in bed, being questioned by others. Later Uncle Charlie will inherit Charlie’s room in the house. Greeting each other at the station, they move towards each with mirroring shots. They share the same name. Twins, doubles, mirrors and the number two abound in the film – a marvellous blog here captures this all in far more detail and insight than I could here.

Uncle Charlie slithers into Santa Rosa like the serpent into the garden of Eden. He offers temptation left, right and centre. The Newton family receive lavish (stolen) gifts. His brother-in-law’s bank gets a investment from the cash Uncle Charlie carries around (he’s old fashioned you see). He laughs and jokes, reminds Charlie’s mother of the joys of her past and inveigles himself into the heart of the family (he even sits at the head of the table). But he’s also a dark, sinister figure, frequently framed at the top of staircases, marching inexorably towards camera and (in one stand out moment) breaking the fourth wall to address us directly while coldly, contemptuously outlining his theory about the pointless burden useless lives have on the rest of us.

He’s played with a charismatic, cold-hearted, jovial wickedness by Joseph Cotton. Cotton is so good as this on-the-surface amiable man, with a soul devoid of any love, it you’ll wish he’d got parts like this more often. Liberated from playing decent best-friends, Cotton dominates the film with a malignant charisma, married with a growing only-just-concealed desperation at the fragility of his fate. Opposite him, Teresa Wright is marvellous as a young woman who finds her sense of morality fully awakened into outrage by this dark presence corrupting everything in her life.

Corruption is central to Shadow of a Doubt – no wonder Hitchcock loved it – with Uncle Charlie turning everything in the simple, honest town into something darker and tainted by his very presence. There is an almost cliched home-spun decency about the town (almost as if co-writer Thornton Wilder was parodying his Our Town), serving to make Uncle Charlie’s modern sociopathy even more of a destructive force.

Shadow of a Doubt is directed with immense care, but a great deal with subtle flourish. Staircase shots abound, to stress sinister motivations, positions of weakness and unease. Characters lurch towards the camera frequently, as if the whole film was hunting us down. An air of menace, lies and danger builds inexorably as Uncle Charlie’s true-nature leaks out. There is also wit: not least from Charlie’s father (a jovial Henry Travers) and eccentric neighbour (a scene-stealing Hume Cronyn) gleefully discussing true crime throughout. There is also Hitchcock’s love of irony, not least in the fact Charlies problems are largely caused by his attempts to conceal a newspaper article that otherwise would have gone unnoticed.

Hitchcock makes his cameo early on as a card player on a train journey. He’s revealed to be holding all the trumps. That’s how he likes it: and perhaps explains his fondness for Shadow of a Doubt. Low key but perfectly constructed, it’s a film that latches onto themes of corruption, dark temptation and ruthless violence. Film logic abounds – who cares that the detective’s investigation is so inept they’d never be employed again – and the second half is crammed with murder attempts as unsubtle as they are ingeniously dark. Shadow of a Doubt feels like a prototype for darker themes of obsession and temptation Hitchcock would explore in the future. Perhaps that’s why he was so fond of it: it’s where he started to spread his wings.