Spielberg explores his childhood in this warm but honest look at the triumph and pain of movie-making and family

Director: Steven Spielberg

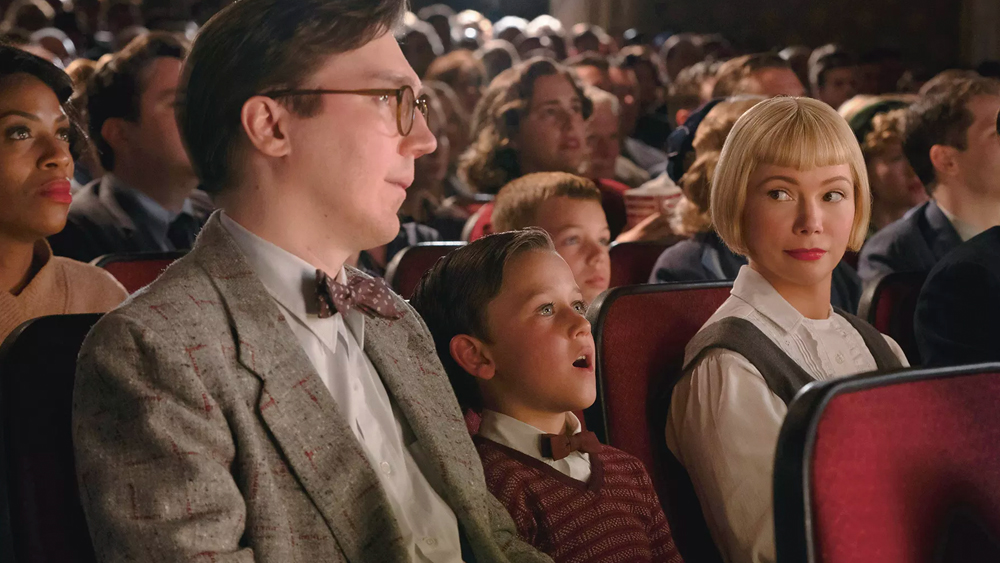

Cast: Gabriel LaBelle (Samuel Fabelman), Michelle Williams (Mitzi Schildkraut-Fabelman), Paul Dano (Burt Fabelman), Seth Rogan (Bennie Loewy), John Butters (Regina Fabelman), Keeley Karsten (Natalie Fabelman), Sophia Kopera (Lisa Fabelman), Mateo Zoryan Francis DeFord (Young Sammy), Judd Hirsch (Boris Schildkraut), Jeannie Berlin (Hadassah Fabelman), Robin Bartlett (Tina Schildkraut), David Lynch (John Ford)

Perhaps no director is more associated with cinema’s magic than Steven Spielberg. And watching The Fabelmans, a thinly fictionalised story about his childhood, clearly few directors have as much of that cinematic magic in their blood. The Fabelmans joins a long line of post-Covid films about auteur directors reflecting on their roots (clearly a lot of soul searching took place in 2020). Surprisingly from Spielberg, The Fabelmans emerges as a film that balances sentiment with moments of pain and a love of cinema’s tricks with the suggestion of its darker powers rewrite reality according to the eye of the director (or rather the editor).

The film follows thirteen years in the life of the young Spielberg, here reimagined as Samuel Fabelman (Gabriel LaBelle, by way of Mateo Zoryan Francis-DeFord). His father Burt (Paul Dano) is an electrical engineer with a startling insight into the way computers will shape the modern world. His mother Mitzi (Michelle Williams) is a former concert pianist turned full-time Mom. The family moves from New Jersey to Phoenix and finally California, as Burt’s career grows. From a young age Samuel is enchanted by cinema, filming startling narrative home movies, packed full of camera and editing tricks. But he and the family are torn between art and science, just as Mitzi’s friendship with “Uncle” Bennie (Seth Rogan), Burt’s best friend, is revealed to go far deeper.

The Fabelmans is both a love letter to cinema and to family. But it’s a more honest one than you expect. It’s got an open eye to the delights and the dangers of both, the pain and joy that they can bring you. The film’s theme – expertly expressed in (effectively) a sustained monologue brilliantly delivered by Judd Hirsch in a brief, Oscar-nominated, cameo as Samuel’s granduncle a former circus lion tamer turned Hollywood crew worker – is how these two things will tear you apart. The creation of art makes demands on you, both in terms of time and dedication, but also a willingness to make reality and (sometimes) morality bend to its needs. And family are both the people who give you the greatest joy, and the ones that can hurt you the most.

Spielberg’s film tackles these ideas with depth but also freshness, lightness and exuberant joy. Nowhere is this clearer than the film’s reflection of Spielberg’s deep, all-consuming love for the art of cinema. Its opening scene shows the young Samuel – an endearingly warm and gentle performance from Francis-DeFord – transfixed during his first cinema visit by the train crash the concludes DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth. So much so he feels compelled to recreate it – much to his father’s annoyance – with an expensive gift trainset, before his mother suggests filming it. Even this 10-year olds film, shows a natural understanding for perspective and composition.

The young Samuel – in an inspired moment of Truffautesque brilliance – is so enraptured with his resulting film, that he plays it repeatedly, projecting it onto his hands, as if holding the magic. No wonder he becomes a teenager obsessed with movie-making, who talks about film stocks and editing machines at a hundred miles an hour, locking himself away for hours carefully snipping and editing footage. The film this young auteur directs – very close recreations of Spielberg’s actual movies – are breath-taking in their invention and the joy. A western with real gun flashes – Burt is astounded at the effect, achieved by punching holes in the film – an epic war film crammed with tracking shots and stunningly filmed action. This is a boy who loves the medium, excited to uncover what it can do, who finds it an expression for his imagination.

He’s clearly the son of both his parents. Burt, played with quiet, loving dignity by Paul Dano (torn between holding his family together and the knowledge he can’t do that), is a quintessential man of science. It’s from him, Samuel gets his love for the nitty-gritty mechanics of film-making, its machinery and precision. But to Burt it’s only a “hobby” – real work is the creation of something practical. So his artistic sensibility films comes from his mother Mitzi, gloriously played by Michelle Williams as a women in a constant struggle to keep her unhappiness at bay by telling everyone (and herself) its all fine. She needs a world filled with laughter and joy.

It’s what she gets from Uncle Bennie (Seth Rogan, cuddly and kind). It’s also where the darkness of both family and film-making touches on this bright, hopeful world. Creating a film of a camping trip the extended family have taken, its impossible for Samuel not to notice at the edge of the frames that Bennie and his mother are more than just friends. His solution? Snip this out of the film he shows the family, then assemble an “alternative cut” which he shows his mother, showcasing the tell-tale signs of her emotional (if not yet physical, she swears) infidelity. The Fabelmans skirts gently however, over how Spielberg’s teenage fear of sexuality in his mother and the association of sex with betrayal may have affected the bashful presentation of sex in many of his movies.

Samuel’s camping film works best as a reassuring lie. He’ll repeat the trick a few years later, turning his jock bully (who flings anti-Semitic insults and punches) into the super-star of his high-school graduation film, a track superstar who is made to look like a superman. Confronted about it, Samuel acknowledges it’s not real – but maybe it just worked better for the picture. It’s as close as Spielberg has ever come to acknowledging the dark underbelly of cinematic fantasy: it can mask the pain and torment of real life and it can turn villains into heroes. His unfaithful Mum becomes a paragon of virtue, his school bully a matinee idol.

Why does he do it? Is it to gain revenge by confronting those who have let him down with idealised versions the know they can’t live up to? Even he is not sure. Perhaps, The Fabelmans is about the young Spielberg reconciling that even if the movies are lies, they can also be joyful, exciting lies that we need: and that there is more than enough reason to continue making them. Just as, angry as we might get with our parents, we still love them.

The film is held together by a sensational performance by Gabriel LaBelle, who captures every light and shade in this journey as well as being uncannily reminiscent of Spielberg. It’s a beautifully made film, with a gorgeous score by John Williams that mixes classical music with little touches of the scores from Spielberg classics. And it has a final sequence dripping with cineaste joy, from a film deeply (and knowledgably) in love with cinema. Who else but David Lynch to play John Ford, handing out foul-mouthed composition tips? And how else to end, but Spielberg adjusting the final shot to match the advice, tipping the hat to the legend?

The Fabelmans creeps up on you – but its love for film and family, its honesty about the manipulations and flaws of both and its mix of stardust memories and tear-stained snapshots feels like a beautiful summation of Spielberg’s career.