Generational clashes lie at the heart of Ray’s heartbreaking second entry in his Apu trilogy

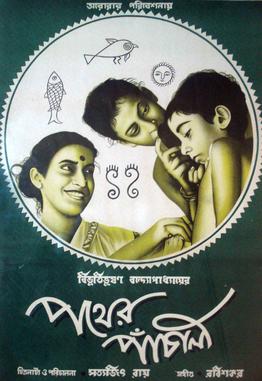

Director: Satyajit Ray

Cast: Kanu Banerjee (Harihar), Karuna Banerjee (Sarbajaya), Smaran Ghosal (Adolescent Apu), Pinaki Sengupta (Young Apu), Ramani Sengupta (Uncle Bhabataran), Charuprakash Ghosh (Nanda-babu), Subodh Ganguli (Headmaster), Moni Srimani (School inspector), Ajay Mitra (Shibnath), Kalicharan Roy (Akhil)

Satyajit Ray initially saw Pather Panchali as a one-off, a story from the works of Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, not the start of a multi-film fable on the life of its young protagonist. But, such was the impact of Ray’s debut, it almost demanded a continuation of the story. Ray then adapted parts of two Bandyopadhyay novels, re-shaping them into a tale of Apu’s late childhood and adolescence, that difficult crossing point between childhood and adulthood. In doing so, he created a film full of life but also profoundly moving and quietly devastating. Rich, confident and powerful, Aparajito may just be even more affecting than its forbear.

Beginning a few years after the conclusion of Pather Panchali Apu (played as child by Pinaki Sengupta and later as an adolescent by Smaran Ghosal) lives in the holy city of Varanasi with his dreaming father Harihar (Kanu Banerjee) and tireless mother Sarbajaya (Karuna Banerjee). Apu is still the same inquisitive, observant, fascinated child he ever was and when his father’s death leads to mother and son returning to the country, he excels at the local school. Winning a scholarship to college at Calcutta, Apu he finds Sarbajaya’s love for him smothering, just as she is heart-broken by his growing distance and reluctance to write or return to visit her.

This universal story of children struggling to outgrow their parents and their parents longing to help them grow but desire to keep them close, a situation causing pain on both sides, that gives Aparajito it’s huge emotional force. We can totally understand why Apu, swept up in the excitement of Calcutta and forging of his own life (one that has the promise of being so much more dynamic than his parents), begins to feel the ties of duty to his mother (almost alone in the world without him) constraining. At the same time, having witnessed the never-ending sacrifice, patience and quiet devotion of Sarbajaya to her son, we want to slap him for his selfishness and lack of thought.

Ray’s film is superb at making us understand the impossible burdens Sarbajaya has taken on herself to raise her son. Ray constantly frames Sarbajaya in the act of waiting: in Varanasi we never see her outside of the courtyard of their shared tenement block, constantly preoccupied with household tasks. Ray frames Sarbajaya frequently in doorways, visually presenting her as someone constantly waiting on the outskirts, shadows cast across her – someone vital for ensuring order, but easy to forget on the outskirts of rooms. It also serves to make her look constantly trapped and overburdened with duty, shadows constantly cast across her.

These burdens magnify for Sarbajaya after the death of Harihar. Apu’s decent father is still a dreamer who lacks the dedication and drive to make something of himself. Do memories of his father’s desire to become a writer ending in a fever in a tenement block, subconsciously drive Apu later? Harihar collapses near the holy river, ill from the damp of the city that he trudges through barefoot night and day, hitting the ground in a shadow lit passageway – much like his wife, as if the city has crushed him with its burdens.

The city seems very different to the young Apu. Ray’s camerawork is gentle, full of leisurely sideways pans, which serve to make the city appear to us as it does to Apu: a never-ending stream of visual wonders. Pans across the riverbanks of the Ganges, full of beautiful temples and river vistas look as magical to us as they do to the young boy. Similarly, the Dickensian hustle and bustle of the city itself, full of streets and alleyways that Apu and his friends rundown with glee feel like treasure-troves of adventure, rather than the never-ending streets trudge they look like when we see them from Harihar’s perspective.

Ray’s camera frequently brings us back to the searching, questioning, fascinated eyes of young Apu, always expanding his horizons. Education and the wonders that books bring him, far beyond the horizons of his mother who can only think about how to bring about tomorrow, offer a similar excitement. Young Apu excels at school and delights in trying to share the wonders he has learned – about science, astronomy and geography – with his mother. Ray shows a mastery of simple montage as years fly by in minutes as we see each of Apu’s passions before a masterful transition with a slow zoom in and out on a lit candle carries across years from Apu as a child to an adolescent.

An adolescent who feels the pull of a world away from what he increasingly sees as the smothering pull of his mother. It is, of course, impossible to watch this without feeling how unfair – but also how natural – this is. Your heart breaks as Apu heads off to Calcutta with only a single cursory glance back to his devoted mother. The mother who still packs his bag, gives him her savings – and asks him to come home as often as he can. You can understand why a young man finds this constraining, even as you want to tell him how sharp his regrets will be as Sarbajaya’s health begins to fail (naturally, the boy falls asleep as his mother timidly confesses her fear of old age and sickness to him).

Apu loves his mother, there is no doubt about that. One vacation, arriving at the train station to return to Calcutta, he decides to turn back (claiming he missed the train) to spend one more day with his mother. He still relies on her wisdom and unreserved love and he thinks often of her in the city. But he’s a teenager and wants his freedom. Sarbajaya even understands this, just as her heart breaks for the loss of and loneliness his departure brings. Is there a sadder shot in the movies as Ray focuses on Sarbajaya slowly sinking down as Apu walks away to his future?

The impact is only increased by the gloriously moving, hollow-eyed performance of Karuna Banerjee, exhausted but untiring in her work to protect family and home. It’s a performance of quiet, bubbling grief and loss tightly packed under optimism and support for her son – a grief that only the audience sees. Smaran Ghosal is also very fine as the adolescent Apu, a boy we can never dislike for very naturally wanting to forge his own path, in a performance that feels extraordinarily real.

The humanity shines out again in Ray’s follow-up to his debut. Moving confidently from location to location, in a novelistic structure translated perfectly to the screen, Aparajito is rich, beautifully told and carries real, unbearable emotional punch for anyone who has ever been a parent or child. Another masterwork in a mighty trilogy.