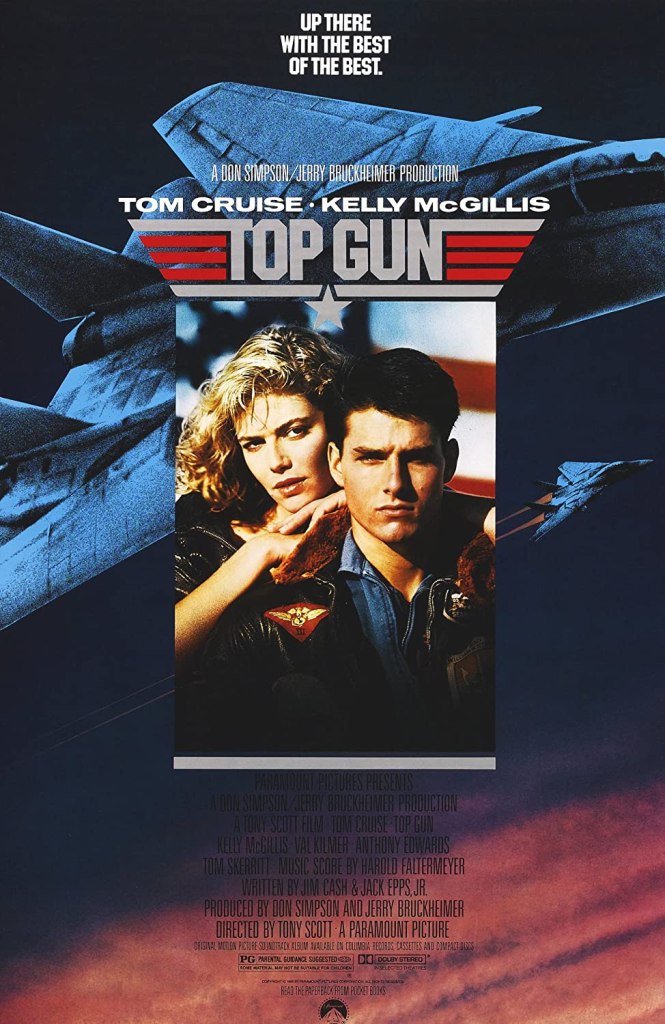

Cruise flies into movie super-stardom in this fun-but-much-worse-than-you-remember flying film

Director: Tony Scott

Cast: Tom Cruise (Lt Pete “Maverick” Mitchell), Kelly McGillis (Charlie Blackwood), Val Kilmer (Lt Tom “Iceman” Kazansky), Anthony Edwards (Lt Nick “Goose” Bradshaw), Tom Skerritt (CDR Mike “Viper” Mitchell), Michael Ironside (LCDR Rick “Jester” Heatherly), John Stockwell (Lt Bill “Cougar” Cortell), Barry Tubb (Lt Leonard ”Wolfman” Wolfe), Rick Rossovich (Lt Ron “Slider” Kerner), Tim Robbins (Lt Sam “Merlin” Wells), James Tolkan (Cdr Tom “Stinger” Jardian), Meg Ryan (Carole Bradshaw)

“I feel the need: the need for speed!” Those words lit up mid-80s cinema screens with one of the biggest hits of the decade. Top Gun is still one of Cruise’s most iconic films, its blasting rock-and-roll soundtrack, beautifully backlit romance and cocksure go-getting self-confidence making it one of the definitive Reaganite 80s films ever made. Its legacy is so all-consuming, it’s always a surprise when you sit down to watch it what a fundamentally average it is.

Its plot, such as it is, can be summarised thus: Tom Cruise cockily flies planes and romances Kelly McGillis until Goose dies. Then he flies planes with the same level of skill but slightly more humility and commits to Kelly McGillis. It all takes place in TOPGUN, the navy’s dog-fight training school for elite pilots. Cruise is Pete “Maverick” Mitchell, super-confident best-of-the-best. Kelly McGillis is the astrophysicist and civilian instructor on the course whose heart melts for Tom’s boyish charms. Anthony Edwards is the doomed Goose (he might as well have a skull and crossbones hanging over him – he’s even got a loving wife and son back home). Val Kilmer is Cruise’s rival pilot, super-professional “Iceman”. The training is fast-paced, macho and culminates in a clash with a (conveniently unnamed) country that definitely isn’t the USSR.

There are three things undeniably great about Top Gun. The songs from Kenny Loggins and Berlin are top notch, full of soft-rock sing-along bombast. Scott shoots the hell out of scenes and the sun-kissed beauty framing the various airplanes and aircraft carriers is superb. With its fetishistic worship of the manly glory of the navy and its equipment, the film had full military backing, a huge boon it exploited for wonderfully executed scenes of dogfights and faster-than-sound planes (Scott even paid $25k to get an aircraft carrier to change course – writing a cheque there and then – so a sunset shot would look better). And of course there is Tom Cruise.

Top Gun is the foundation stone in the Church of Tom Cruise, defining a persona Cruise would effectively riff on for huge chunks of his career. Pete Mitchell is so cocksure he’s even called Maverick. But, as well as being arrogant and over-confident, he’s preternaturally skilled, boyishly enthusiastic, strangely vulnerable, yearns for affection, wins people over with a grin and goes through a crisis of confidence that sands down his negative qualities while never touching his courage, skill and likeability. Cruise cemented his eye-catching charisma and relatability: audiences wanted to be him or be with him. A huge chunk of its massive success is down almost exclusively to what a star Cruise is and how easily he makes this hackneyed stuff work.

The rest is a bizarre mix of half-formed plot ideas, weakly sketched characters and a plot so shallow it almost doesn’t deserve the name. Top Gun is all about a cool guy flying planes accompanied by some excellent songs. There is no depth to its character exploration. There is a dim suggestion Maverick needs to mature (with Goose as the sacrificial lamb to prompt that development) but it’s barely explored. It has no shrewdness in its look at the risk-taking intensity of flying or the type of personalities it might attract. The training is awash with familiar tropes: hotshots, grizzled trainers (two of them in Skerritt and Ironside!) mixing growls with behind-his-back grins at Maverick’s pluck. His rival is the anthesis of Maverick, but (gosh darn it!) he eventually learns to respect him.

The central romance seems thrown in because a film like this needs it – it’s very much An Officer and a Gentlemen in the skies. Maverick’s true emotional love story is with Goose – this surrogate brother/uncle providing Maverick’s only friendship and the vicarious family this Cruise archetype character secretly longs for. But gosh darnit, it’s Hollywood so gotta have a beautiful woman for our hero to manfully seduce. Poor Kelly McGillis looks rather uncomfortable in her ill-shaped and poorly developed character, while her love scenes with Cruise are acted with a slobbering over-intensity that suggests both of them are trying too hard (he constantly kisses her tongue first, which is gross). Perhaps they wanted to really go for it in the hope viewers would overlook the obvious homoerotic tensions of most of the film.

Oh those tensions! Top Gun drips with gleaming, tanned half-naked men squaring up to each other in dressing rooms – and that’s not even mentioning the infamous volleyball sequence (where only Edwards, bless him, wears a t-shirt). Characters forever utter variations on “I’ll nail his ass” lines. Iceman and Maverick take part in a homoerotic-tension fuelled rivalry that culminates in an explosive dog-fight climax and a loving embrace on the deck of an aircraft carrier.

It’s hard to tell how much all this was a joke, and how much Scott, Bruckheimer and Simpson just didn’t notice in the middle of all their glistening, back-lit, fast-paced shooting of military muscle (in every sense) how gay it might look. Maybe they thought people wouldn’t notice either amongst all the military machinery (this must be Michael Bay’s favourite ever film). Top Gun’s aerial footage is super impressive (though it is funny noticing now that famous daredevil Cruise clearly does all his cockpit shots in front of a green screen) even if the whole film feels like an MTV video to promote its knock-out songs.

Top Gun is still fun, even if that’s mostly mocking the nonsense and emptiness it’s built upon. Nothing much really happens, its plot so flimsy it barely stands up against the Mach-9 force of its planes. But it’s got Cruise at his blockbuster best – and when you’ve got that you don’t really need anything else. It’s poorly written, junkfood trash all framed in a fetishistic beauty – but it’s sort of goofy, stupid, empty fun.