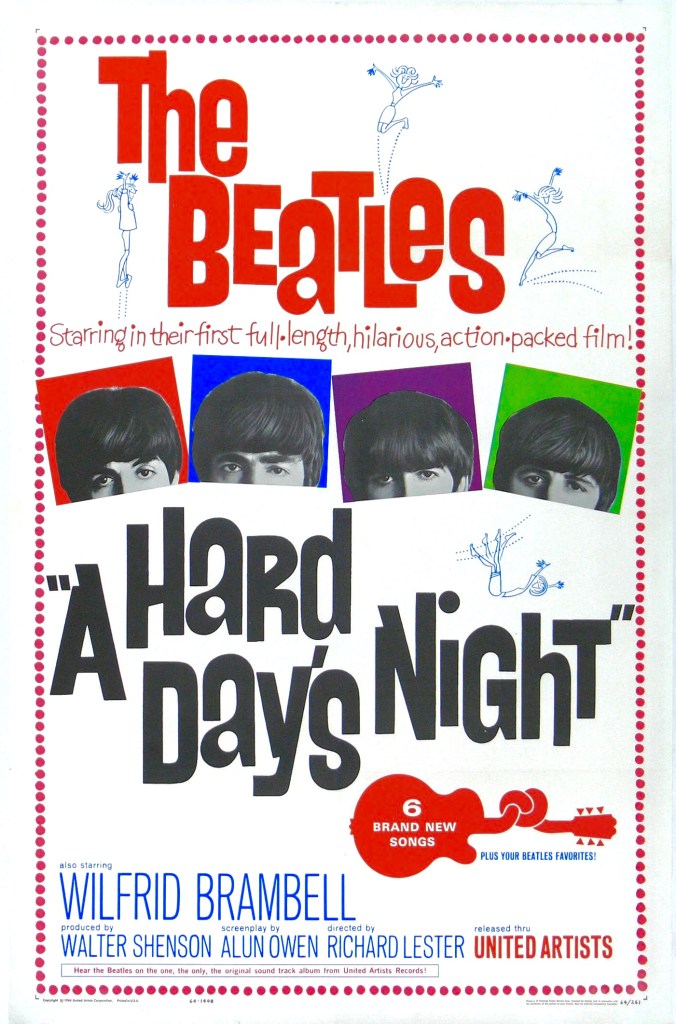

The Fab Four conquer the movies in this fast-paced and funny road movie

Director: Richard Lester

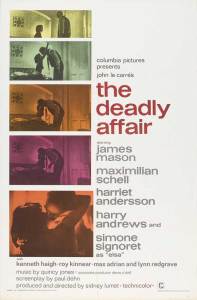

Cast: The Beatles, Wilfrid Brambell (John McCartney), Norman Rossington (Norm), John Junkin (Shake), Victor Spinetti (TV Director), Anna Quayle (Millie), Richard Vernon (Man on Train), Kenneth Haigh (Simon Marshall)

In 1964 they weren’t just the most popular music act: they basically were music. Everywhere they went they were met by crowds of screaming fans. They’d conquered America. They were no longer four lads from Liverpool: they were The Beatles. They were numbers 1-5 in the States, their last 11 songs had gone to number one, they were the most popular people on the planet. Of course, it was time for them to conquer the movies.

What’s striking is that A Hard Day’s Night could have been like any number of god-awful Elvis Presley films, with the King awkwardly playing a series of characters shoe-horned into plots based on songs. Richard Lester would do something different – and along the way he’d arguably invent the music video (when told he was the father of MTV, Lester famously asked for “a paternity test”) and the mockumentary all in one go. Lester placed the fab four into a day-in-the-life road movie, mixed with silent-comedy inspired capers and Marx Brothers style word play, in which they would play versions of their various personas in what basically amounted to a series of fly-on-the-wall sketches.

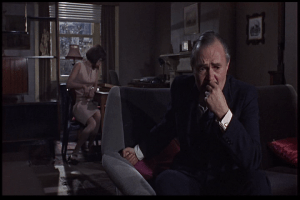

The film follows the gang in Paul’s (fictional) grandfather John (“Dirty old man” Steptoe’s Wilfrid Brimbell) complains move from “a train and a room and a car and a room and a room and a room”. (In a running gag lost on those not au fait with 60s British sitcoms, he is repeatedly called “clean”). In other words, we see the Fab Four shuttle to London, answer questions at a press conference, skive-off to prat about in a park then go through a series of rehearsals (with interruptions) before performing on TV and choppering off to their next appointment. It’s non-stop (even their night-off is filled with answering fan-mail – and pulling Grandad out of casino) work, work, work and any time outside is spent running from a mob of screaming fans. A Hard Day’s Night indeed.

Lester shoots this with an improvisational energy that feels like its run novelle vague through a kitchen-sink drama. He’s not averse to Keystone Kops style chases, sight gags and letting the camera bounce and jerk around with the actors. If things go wrong – ten seconds into the film George and Ringo fall over during a chase scene, get up and start running again while John laughs his head off – Lester just ran with it and kept it in. Everything feels like it has the casual, cool energy of just sticking the camera down and watching four relaxed, cool guys shoot the breeze.

It helps that he moulds four decent performances from a band that, let’s be honest, was never going to trouble the Oscars for their acting. Screenwriter Alun Owen – whose Oscar-nominated script is awash with pithy one-liners and gags – spent a couple of weeks with the boys and from that essentially scripted them four personas best matching their real-life attitudes. John becomes a cocksure smart-arse, with a quip for every corner. Paul an earnest, decent guy with a taste for wacky gags. George a shier, poetic type. Ringo the closest the band gets to a sad-sack loser, but also the most down-to-earth. Essentially, with these scripted “selves” the band were encouraged to relax and go where the mood takes them.

It works. Of course, it helps that the Beatles are (a) really cool and (b) totally relaxed with themselves, with Lester encouraging an atmosphere where the four feel less like they are acting and more like they are just being. There is an impressive naturalness about this film – really striking since it’s full of silly stuff, from the four hiding in a work tent to a car thief being roped in by the police to drive them through a chase – that means it catches you off guard. After a while you kick back and relax along with the people in it. That’s the sort of casual cool that’s impossibly hard work to pull off.

The musical sequences also feel spontaneous. When the Beatles bust out their kit and do a number on the train among the baggage it makes as much sense as them performing their stuff in the studio. It all stems from confidence – the sort of confidence that makes the group seem cheeky rather than cocky. There is a vein in A Hard Day’s Night of thumbing your noise at the posh, privileged world that was being gate-crashed by four working-class Scousers. It’s hard not to side with the Beatles when they tease Richard Vernon’s snobby city gent on the train (“I fought a war for you lot” he sniffs “Bet you wish you’d lost now” John snarks) or smirk at the deferential police eye these working class lads with suspicion.

What A Hard Day’s Night does best of all is make the Fab Four look like Four Normal Guys. They always look slightly dumbfounded by the pace of their life and the riotous reception from fans. They always seem like they’d be happier joking around or, as Ringo does when he bunks off for some time alone, wandering along chatting with people and dreamily watching the world go. They treat the media attention (and stupid questions) with straight-faced but ridiculous answers (“What do you call this haircut?” “Arthur”) and never feel or look like fame has corrupted them. Their manager Norm (a fine Norman Rossington) essentially treats them like four naughty schoolboys.

A Hard Day’s Night flies by in less than 90 minutes. It’s charm, wit and Lester’s sparkling imagery (the boys pratting around in the park did indeed inspire about a million MTV videos) and ability to shoot musical gigs in imaginative exciting ways makes it almost certainly the finest music-star film ever made – and inspired generations of comedies to comes. No wonder it made the Beatles number one at the Box Office and the Charts.