Brilliantly shot racing is the centre piece of this straight-forward, massive advert for the sport

Director: Joseph Kosinski

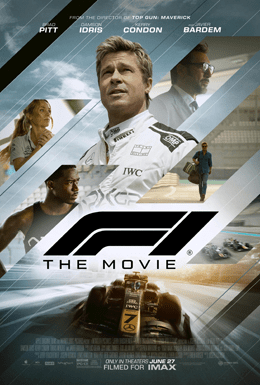

Cast: Brad Pitt (Sonny Hayes), Damson Idris (Joshua Pearce), Kerry Condon (Kate McKenna), Javier Bardem (Rubén Cervantes), Tobias Menzies (Peter Banning), Kim Bodnia (Kaspar Smolinski), Sarah Niles (Bernadette Pearce), Will Merrick (Hugh Nickleby), Joseph Balderrama (Rico Fazio), Callie Cooke (Jodie), Shea Whigham (Chip Hart)

No one exactly says it, but “I feel the need for speed!” hangs over the whole of F1. Set in a fictional F1 team – although every other team, driver and team manager we see is real, with F1 superstar Lewis Hamilton serving as both producer and ‘final boss’ for the film’s conclusion – it’s by-the-numbers plot is the glue holding together a host of excitingly cut scenes of cars zooming round straights and bends.

It’s half-way through the season and struggling APXGP don’t have a point, and if they don’t win one of the remaining nine races the corporate suits will sell the team. Owner Rubén (Javier Bardem) tries a Hail Mary: signing up ex-F1 prodigy turned racing gun-for-hire Sonny Hayes (Brad Pitt) to pull it out of the bag. But can Sonny’s old-school ways mesh with his hi-tech team, led by technical director Kate (Kerry Condon) and ambitious, social-media friendly team-mate Joshua Pearce (Damon Idris)?

F1’s alternative title is F1: The Movie and it’s basically a massive advert for the sport. (In fact, not just F1 since it drips with product placement in almost every frame.) With the glamourous face of Brad Pitt front-and-centre, this is all about dragging more eyeballs onto the sport, presented here as an impossibly balls-to-the-wall, high-octane, Fast and Furious style, non-stop adrenaline rush with every race awash with excitement, unpredictability and thrills. (No first-to-last lap processions here!) Of the nine Grand Prixes we see, not a one goes by without a pulsating crash, gloriously skilled over-takes or final lap miracles. This F1 putting its best suit on and asking you out on a date.

After his success with Top Gun: Maverick, Kosinski was a logical choice to bring the same excitement to cars as he did to planes. The camera gets down and low with the drivers, either sitting with the car as it zooms on the track or zeroing in on the drivers’ faces as the scenery whips by. It’s tightly edited, often cut perfectly to the beat of various classic rock songs, the film sounding like a Top Gear Greatest Hits compilation CD. This is some of the best edited and assembled footage of racing you’ll see (not surprising since they had F1’s full co-operation) and is the clear highlight.

F1 pitches for the widest possible audience by making sure even the biggest rube watching can follow the action with almost every second of race footage accompanied by commentary explaining exactly what’s happening and why. Sky commentators Martin Brundle and David Croft probably have more dialogue than most of the actors, feeding us Spark Notes F1 lore, probably irritating the petrol-heads but a godsend to newbies. Interestingly, they don’t talk about how much the film slightly mis-represents the rules. For starters, any driver who carried out as many ‘accidental’ minor collisions as Sonny does in an early race (to provoke the safety car’s emergence and make it easier for his team to score a point) would probably find himself on a one-way ticket to a ban. Never mind the APXGP car being crap at qualifying but unbelievably good in races. I guess, due to the drivers who the film is selling as gods of the gearstick – which is also why a F1 rules official (played by Mike Leigh regular Martin Savage) is portrayed as humourless bureaucrat for enforcing the sports own labyrinthine red tape.

Anyone expecting an F1 season to play out like F1 is in for a disappointment. But then, this is about dragging you in to see if you get sucked in by the moments when the sport does live up to this. Everything else is completely subservient to selling the experience, hence the paint-by-numbers script. There is scarcely a single narrative beat in the film you can’t predict from the set-up, and every character is only lifted from being a lifeless caricature through the charisma of the actors. It’s quite old school really: part of suppressing the truth of F1 (the engineering is key) in favour of the romantic (the drivers are the magic sauce that brings the win).

F1 has a fawning, romantic regard for the sort of old-school, manly no-nonsense of Brad Pitt, the film largely being about establishing everyone would perform better if they took more than a few leaves out of his book. For starters, Damson Idris’ JP would really become a winner if he focused on the driving not social media and started training like Pitt does (running the track, catching tennis balls and flicking playing cards) rather than putting trust in a high-tech gym. Pitt’s Sonny is never wrong in the film with mistakes only happen when his advice is ignored. He’s shown to have the dedication and in-bred knowledge to zero on the key data about the cars (F1 heavily endorses science in the cars, even as it subtly disparages science in the gym) to hone its performance. His samurai-life view, of moving from race to race (from Daytona to F1 and on) only dreaming of speed and the pure joy of driving is relentless praised.

Saying that, F1 does rather charmingly fly the flag of the importance of teamwork (just so we really get it, Pitt pointedly states several times it’s a team sport, where a second saved by a pit stop team is as vital as a second gained by the driver). F1 goes into detail of how important pit stop teams, racing strategy and technical design of the car are to success. Again, it feels like a pointed rebuttal of an argument non-fans of the sport might make, that it’s just men driving fast in a circle for about two hours.

Fundamentally though, F1 offers very old-fashioned entertainment, with very expected cliches. Kerry Condon’s technical director may speak briefly about the hurdles she’s had to climb over to become the sport’s sole female in her role – but her primary role is as really as coach and love interest to Pitt. Anyone who needs more than five seconds to work out that Tobias Menzies’ smirking corporate suit probably isn’t the ally he claims to be needs to see more movies. Sonny and JP’s relationship follows familiar rail tracks of rivals-turned-friends and the film even has the motor sport equivalent act four “you’re off the case” moment beloved of movies. But, if I’m honest, Pitt doesn’t have the charm and vulnerability that Cruise does (Sonny is so cool and collected, he’s never as relatable or loveable as he needs to be), and the film lacks a strong emotional centre to invest in. It’s entertaining enough of course, but it never finds a real, durable, re-watchability for anything other than the fast-moving cars at its heart.