Kirk Douglas is a boxing heel in this noirish melodrama full of excellent moments

Director: Mark Robson

Cast: Kirk Douglas (Midge Kelly), Marilyn Maxwell (Grace), Arthur Kennedy (Connie Kelly), Paul Stewart (Tommy Haley), Ruth Roman (Emma), Lola Albright (Palmer), Luis van Rooten (Harris), Harry Shannon (Lew), John Day (Dunne), Ralph Sanford (Hammond), Esther Howard (Mrs Kelly)

What does it take to get to the top? Skill, luck, ambition, determination – and sometimes just being a ruthless bastard. Midge Kelly (Kirk Douglas) as all five of those skills in spades, flying from bum to champ in just a few short years, burning every single bridge along the way. Champion tells the ruthless story of how Kelly alienated his devoted lame brother Connie (Arthur Kennedy), dropped the trainer (Paul Stewart) who discovered him in a heartbeat and used and tossed aside a host of women: dutiful wife Emma (Ruth Roman), would-be femme fatale Grace (Marilyn Maxwell), artistic, sensitive Palmer (Lola Albright) wife to his new manager. As he enters the ring to defend his title against old rival Johnny Dunne (John Day), will all these chickens come home to roost?

Champion is deliciously shot by Franz Planer with a real film noir beauty, in particular the vast pools of overhead light that fill spots of the backstage areas of the various venues Midge fights in. Its boxing is skilfully (and Oscar-winningly) edited into bouts of frenetic, enthusiastic energy – although you can tell immediately that no one in this would last more than 90 seconds in a real ring – and it manages to throw just enough twists and turns into its familiar morality tale set-up to keep you on your toes and entertained. In fact Champion is a gloriously entertaining fists-and-villainy film, full of well-structured melodrama and decently drawn moral lessons. It’s the sort of high-level B-movie Studio Hollywood excelled at making.

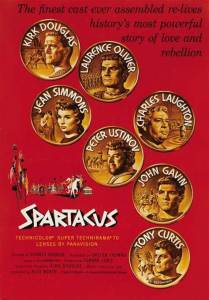

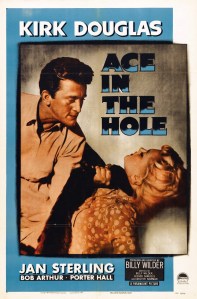

For a large part it works because Douglas commits himself so whole-heartedly to playing such an absolute heel, the kind of guy who knows he’s a selfish rat but just doesn’t give a damn. Douglas was given a choice of a big budget studio pic or playing the lead in this low-budget affair, chose Champion – and his choice was proof he knew where his strengths lay as an actor. Midge Kelly is the first in a parade of charismatic, ruthless exploiters that Douglas would play from Ace in the Hole to The Bad and the Beautiful. Kelly is all grinning good nature until the second things don’t go his own way: and then you immediately see the surly aggression in him.

Its why boxing is a good fit for him. He doesn’t quit a fight – pride won’t let him. It’s the quality that Tommy sees in him, after Midge is literally pulled in off the street to pad up the under-card at a challenger’s fight night. Clueless as he is about boxing technique, he refuses to stay down and picks a fight with the promoter on the way out when cheated out of his fee. Champion shows how, for resentful people like Kelly, pugilism is a great way of getting your own back when you feel life has screwed you in some way. Perhaps that’s why he goes for his opponents with such vicious, relentless energy and why he takes such a cocky delight in beating the hell out of them. In fact, Champion could really be a satire on the ruthless, put-yourself-first nature of much of Hollywood, with both Connie and Tommy commenting that the fists-and-showbiz world is a cutthroat one.

What Champion makes clear though is that Kelly isn’t corrupted by fame. For all Douglas’ charming smile, there is a cold-eyed sociopathy in him from the start. Kelly performs loyalty, but it’s always a one-way street. He’ll assaults those who call his weak-willed, more cynical, crutch-carrying brother Connie ‘a gimp’, but he has no real sense of loyalty. He doesn’t even pause for a second when seducing Emma (daughter of the diner the brothers end up working at on arriving in LA) for a quick fumble despite knowing Connie’s feelings for her. Later, criticised by Connie, he’ll just as angrily lash out at Connie, mocking his disabilities, the second his brother starts to make decisions of his own.

Kelly’s ruthlessness towards women is also clearly something innate. He’ll whine like a mule when forced (virtually at gunpoint) to marry Emma, who he’ll immediately leave behind with no interest of hearing from again (until she finally develops some feelings for Connie of course, at which case he seduces her as a point of pride). His sexual fascination for the manipulative Grace – a purring Marilyn Maxwell – quickly burns out, again not pausing for a second in chucking her aside, all but flinging dollar bills on a table as he goes. Even more heartlessly, after showing some flashes of genuine courtliness in his romantic interest in Palmer (a very sweet Lola Albright), he happily takes a cheque from her husband (right in front of her) to never see her again. None of this comes from fame: it’s the sort of guy Kelly is.

And, as Douglas’ smart, self-absorbed performance makes clear, it’s because deep down Kelly always thinks he is the victim and the world owes him a living. There is a strong streak of self-pity in Douglas’ performance, bubbling just below the surface combined with a narcissistic need to be loved by strangers even while he’s reviled by everyone who knows him. There is an escape from inadequacy for Midge in fighting: something he keeps coming back to time-and-again in complaints about the unjust treatment the world has given him in the past, used to justify any number of lousy actions.

Champion unfolds as an interesting study of a deeply flawed, increasingly unsympathetic character with a huge drive to destroy other people, either by words or fists. An excellent performance by Douglas is counter-poised by a host of other strong turns, especially from Arthur Kennedy, whose Connie effectively trapped in an abusive relationship and Paul Stewart’s unromantically realistic trainer who knows the score long before anyone else. Handsomely shot and directed with a melodramatic flair by Mark Robson, it can enter the ring with any number of other boxing films.