Schwarzenegger becomes an icon in Cameron’s masterpiece, a darkly gripping sci-fi chase-thriller

Director: James Cameron

Cast: Arnold Schwarzenegger (The Terminator), Michael Biehn (Kyle Reese), Linda Hamilton (Sarah Connor), Paul Winfield (Ed Traxler), Lance Henriksen (Hal Vukovich), Bess Motta (Ginger), Rick Rossovich (Matt), Eal Boen (Dr Peter Silberman), Bill Paxton (Punk)

“It can’t be bargained with. It can’t be reasoned with. It doesn’t feel pity, or remorse, or fear. And it absolutely will not stop… ever, until you are dead!”

If that description doesn’t grab your attention, I don’t know what will. James Cameron cemented his place in cult-film history with The Terminator, such a pure shot-to-the-heart of filmic adrenalin, its hard to think it’s been bettered since. Cameron takes a fairly simple story – essentially a long, relentless chase – and fills it with energy, black humour and a genuine sense of unstoppable menace, in a film that barely draws breath until it’s over an hour in and then promptly throws you straight into a final action set-piece. It uses its low budget effectively to create a world of mystery and dark suggestion and leaves you gagging for more. So much so, they’ve tried to recapture the thrill ride six times since (and only Cameron did it right, with Terminator 2).

It’s 1984 and two naked people arrive in Los Angeles in a ball of light. They’re both from 2029, time-travellers looking for the same woman. One of them nicks a tramp’s piss-stained trousers and runs from the police. The other is a stoic, impassive mountain of muscle who offs a few violent punks after they refuse his blunt instruction to hand over their clothes. Which one do you wish you were eh? Unfortunately, the second one is a Terminator (Arnold Schwarzenegger), a machine in the skin of a man sent to eliminate Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton), mother of the future leader of the post-apocalyptic human resistance to the machines. The first is Kyle Reese (Michael Biehn), the man sent to save her. Tough gig, since the Terminator is relentless, almost invulnerable and holds all the cards.

The Terminator is pulpy, dirty, punchy film-making – and its huge success became James Cameron’s calling card for a lifetime of success. Set in a neon-lit, dingy Los Angeles (it never seems to be daytime in The Terminator), it taps into the core of a million nightmares, the fear of being chased and nothing you do ever sees to get you further away. It’s a really elemental fear which The Terminator brilliantly exploits, as impassive and impossible to negotiate with as your deepest, darkest dreads. Throw into that Cameron’s gift for tension and you’ve got the almost perfect thrill-ride.

It’s also a film that gives us the perfect level of information we need. Unlike the cops (and Sarah Connor) who can’t believe this story Reese is peddling them that they are up against an unstoppable metal killing machine, we know from the start the whole story. It’s enough for us to feel a cheeky frustration as they bend over backwards to fit logical explanations to the things they’ve seen and for us to feel the sneaking dread that storing Sarah away in a police precinct crammed full of heavily armed cops isn’t going to make a jot of difference. He won’t let anything stop him.

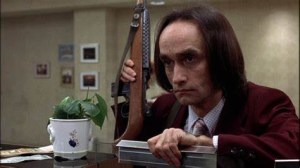

Is it any wonder quite a few people came out of the film sympathising with Sarah and Kyle – but feeling a sort of guilty admiration for the Terminator? This is the foundation stone of the Schwarzenegger cult, his role as the monosyllabic machine sending him into the upper echelons of Hollywood stardom. Cameron’s original idea was the Terminator should be a perfect infiltration unit, the sort of guy who wouldn’t stand out in a crowd (the original choice was Lance Henriksen, relegated instead to the second-banana cop behind Paul Winfield’s folksily doomed decent guy, fundamentally out of his depth). That went out of the window when Schwarzenegger came on board: say what you like about the Austrian Oak, but he stands out in a crowd.

Why is the Terminator darkly cool? (After all literally no one ever pretended to be Kyle Reese, but everyone has put on a pair of shades and said “I’ll be BACH”.) Because he embodies all the qualities we’ve been taught by films to respect. He’s strong and silent, calm and confident, never complains, doesn’t need help and never gives up. He’s exactly the sort of guy Hollywood has cast admiring eyes at since film spooled through a camera. We can’t help ourselves.

The film becomes about Schwarzenegger (even if he’s not in the last set piece, replaced by a budget-busting CGI android). Cameron knew how to get the best out him, his tiny number of lines (17 in total) delivered in his emotionless, euro-accent make him seem mysterious, different and cool, frequently responding with either deadpan seriousness or sudden violence. His under-statement lines are funny because we anticipate already the bloodbath that will follow. And, unlike despicable villains, he’s not motivated by greed, jealousy or wickedness: he’s almost the quintessential American hero, taking care of business – it just so happens his business is killing people.

Reese should be someone we admire more: he’s a plucky, resourceful underdog. But, unlike the actions-rather-than-words Terminator, he’s got to speak all the time – while the Terminator is a killing machine, Reese is the exposition machine. Biehn does a terrific job with a difficult role, a decoy protagonist who spends much of the movie alternating between gunplay and spitting out reams and reams of exposition explaining to anyone and everyone the future and terminators. On top of that, while his opponent gets on with, Reese’s constant refrain of how scared he is and everyone else should be (who wants to hear a hero say how terrified he is eh?) and his frustrated whining at no-one listening to his fantastic story marks him as weak. Charismatic heroes persuade their audiences: no one believes Reese until they are literally watching Arnie shrug off a whole clip of ammo.

Reese is, in any case, a decoy protagonist of sorts. His romantic longing for Sarah (having fallen in love with her photo in the future) and nurturing personality actually mark him out as the more conventional ‘female lead’. In the first of several films where Cameron would show-case heroic female characters, the actual ideal rival for the machine is Sarah. One of the most interesting things about The Terminator is watching Linda Hamilton skilfully develop this character from ordinary young woman into the sort of archetypal Western hero the film ends with her as (she even gets the sort of badass kiss-off line “You’re terminated FUCKER” you can’t imagine the less imaginative Reese saying).

On top of this The Terminator is a triumph of atmosphere. With its synth-score, it has an unsettling quality from the off helping to build the sense of grim inevitability that is its stock-in-trade. Just like the Terminator’s never-ending pursuit, the whole film is a well-judged, inevitable, time-loop. Sending people back in time turns out to be the very thing that guarantees that future will happen. Throughout, Cameron’s little titbits about the future (partly constrained by budget) are perfect in giving us just enough information to understand the stakes but leave enough mystery for us to be so desperate to know more, we fill in the gaps from our imagination.

But the reason The Terminator works best is that it’s an undeniably tense thrill ride, an extended chase sequence that rarely eases off and never loses its sense of menace. You never feel relaxed or safe while watching The Terminator and never for a moment that its heroes are on a level playing field with their opponent. Atmospheric, tense and terrifying, it walks a brilliantly fine line (so much so, the Terminator methodically massacring a precinct full of cops is both unnerving and the most popular scene in the film) and never once let’s go of your gut. It’s not only possibly the best, most perfect, Terminator film made also still one of Cameron’s finest hours.