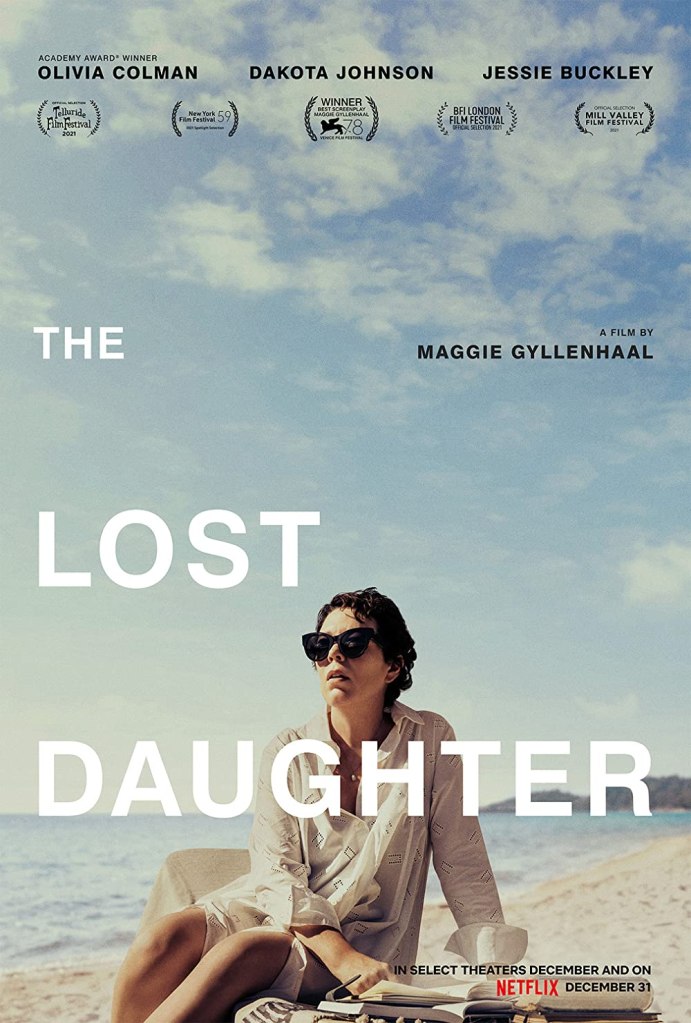

Motherhood, loss and guilt are at the heart of this over-extended drama that doesn’t feel like it focuses on the right things

Director: Maggie Gyllenhaal

Cast: Olivia Colman (Leda Caruso), Jessie Buckley (Young Leda Caruso), Dakota Johnson (Nina), Ed Harris (Lyle), Dagmara Dominczyk (Callie), Paul Mescal (Will), Peter Sarsgaard (Professor Hardy), Jack Farthing (Joe), Oliver Jackson-Cohen (Toni), Athena Martin (Elena), Robyn Elwell (Bianca), Ellie Blake (Martha)

Leda (Olivia Colman), a professor of Italian Literature, holidays in Greece. That holiday is disturbed by the arrival of a noisy, aggressive family from Queens. A member of that family, unhappy young mother Nina (Dakota Johnson) loses her daughter on a beach. Leda finds her, but it triggers her own unhappy memories of motherhood (Jessie Buckley plays the young Leda). She impulsively steals the child’s beloved doll, as her paranoia and mournful reflections grow.

Maggie Gyllenhaal’s directorial debut is a confident, assured piece of film-making, but I found it a cold and slightly unsatisfying film. There is a fascinating subject here, that the film fails to really tackle. One of life’s great unspoken expectations is that everyone should find being a parent – especially being a mother – hugely rewarding. This film studies a woman who didn’t, but still wants to reassure us of the love and happiness found in the bond with a child, no matter your mistakes as a parent. In doing so, it marginally ducks an important societal issue and reaches conclusions that feel predictable, for all the ambiguity the film ends with.

Colman’s expressive face and ability to suggest acres of unhappiness in a forced smile or gallons of frustration with a single intake of breath, are used to maximum effect. Leda is a woman comfortable with her own company, forced and uncomfortable in conversation, her eyes flicking away as if looking for an exit. She seems confused about how to respond to the quiet advances of handyman Lyle (a gentle Ed Harris) and increasingly resents the intrusion into her holiday of outsiders.

How much is this slightly misanthropic, isolated view of the world her natural personality, and how much has it grown from her choices in the past? Flashbacks reveal her struggles as a mother – and the strained relationship with her children today – and it’s clear Leda is a bubble of confused emotions, uncertain about what she thinks and feels.

That past, to me, is the real area of interest, rather than the distant, cold woman those choices have created. I’d argue a stronger film – and one that would feel like it was really making a unique point – would have focused on the younger Leda. Expertly played by an Oscar-nominated Jessie Buckley –brittle and growing in claustrophobic depression – she loves her two girls. But, most of the time, finds them overbearing, all-consuming and more than a little irritating. She’ll laugh at their jokes and be terrified when one of them gets lost, while still resenting their domineering impact on her life.

When she wants to work, they demand attention. When her daughter has a small cut on her finger, Leda is repeatedly asked to kiss it better like a broken record. Leda gives her other daughter her own childhood doll – and then throws it out of a window in fit of hurt fury when the daughter covers it in crayon and says she doesn’t like it. The kids get in the way of everything: be it work (she retreats behind headphones to focus), holidays, sex with her husband or even masturbation.

Her feelings go beyond post-natal depression. She is someone who genuinely loves her children, but can’t bear the idea of mothering them. This is the meat of the film, far more than the present-day narrative. Gyllenhaal sensitively tackles a rarely discussed topic: what can we do if we find parenthood was a mistake? Knuckle down or give up and run away? A film exploring this could have been compelling: but it only takes up a quarter of an over-extended film.

Instead, by focusing on the maladjusted present-day Leda, the film presents her motherhood difficulties as the root cause of her problems. Leda sees a potential kindred spirit in young mother Nina – a brash and exhausted Dakota Fanning – who seems equally frustrated by parenting. But Leda is so insular and self-obsessed, is she only seeing what she wants to see? If she thinks Nina is also failing as a mother, will that make her feel better about her own failures?

The Lost Daughter is an unreliable narrator film – and Gyllenhaal expertly suggests much of what we see are Leda’s perceptions rather than necessarily the truth. The menace from Nina’s loud and aggressive extended family is a constant presence: but is it real, or just Lena’s paranoia. Does the family really cover every tree with a missing poster for a child’s lost doll, or does it just that way to Leda? Does Nina share Leda’s own resentments with motherhood, or does Leda just want her to?

It’s a subtle ambiguity that continues until the film’s close. It leaves many questions unanswered and open to the viewers interpretation. Different viewers will take very different messages from it. But for me, the film wasn’t quite interesting enough – and shied away from exploring the questions of guilt and doubt about parenthood. At no point does Leda even voice the possibility that she regrets having kids – for all that she surely does – which feels odd. For me the film takes a long time to not quite say as much as I feel it could have done.