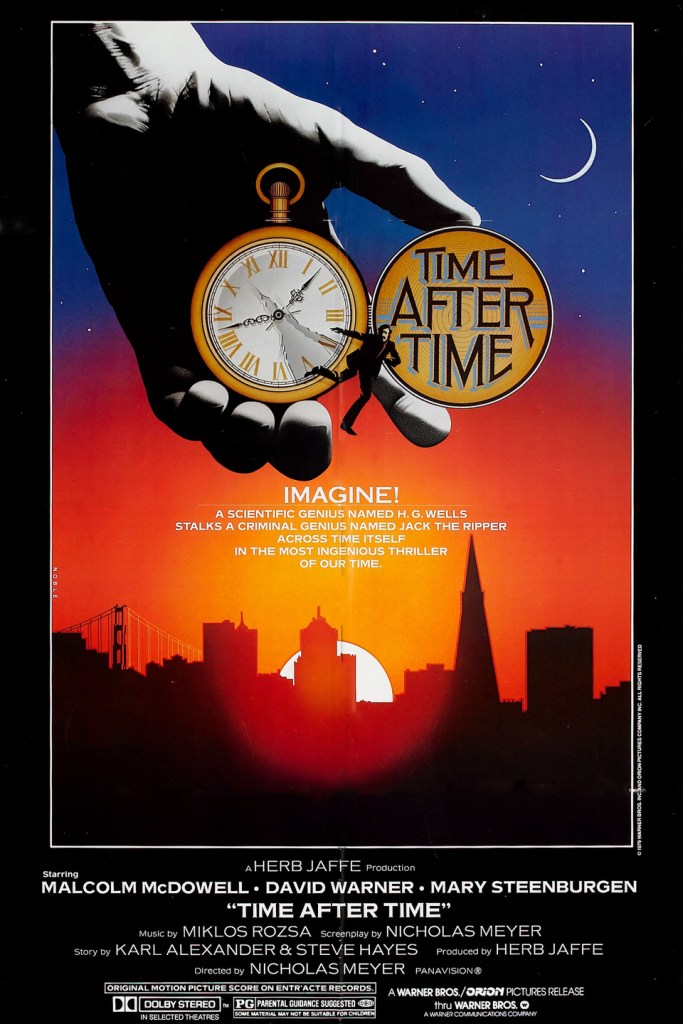

HG Wells zooms through time on the trail of Jack the Ripper in this surprisingly charming time travel romantic thriller

Director: Nicholas Meyer

Cast: Malcolm McDowell (HG Wells), David Warner (Dr John Leslie Stevenson), Mary Steenburgen (Amy Robbins), Charles Cioffi (Lt Mitchell), Kent Williams (Assistant), Patti d’Arbanville (Shirley), Joseph Maher (Adams)

1979 was clearly the Year of the Ripper. New conspiracy theories abounded on his mysterious identity. In Murder By Decree, Sherlock Holmes took on the investigation. And in Nicholas Meyer’s Time Travel fish-out-of-water drama, he pops up in 1970s San Francisco, still up to his wicked ways. How did he get there? Well, imagine instead of just writing The Time Machine, HG Wells had actually built it: and that, during a dinner with a doctor friend, he not only discovers his friend is the infamous killer, but watches him pinch his time machine to escape the long arm of the law.

HG Wells is played by Malcolm McDowell – who surely when he was sent the script assumed he was being asked to take a look at the role of the Ripper – who uses his machine to follow the Ripper to the 1970s to find him. The Ripper is played by David Warner (one of the few actors even more demonic than McDowell), and he’s rather more at home in the 1970s than Wells, who expected to find a utopia. Wells is helped by Amy Robbins (Mary Steenburgen), who is drawn to this charming Englishman, who she believes is a Scotland Yard detective on the hunt for a serial killer.

Meyer’s first film is a little raw – you can see he’s still learning his craft, a few shots are a little rough around the edges in their framing and some plot points and transitions are not easy to follow – but rather charming, for all it’s about the hunt for a serial killer. Meyer gets a lot of affectionate comic mileage from Wells – the quintessential gentle Englishman, timid but determined when riled – working out the social rules of the 1970s. From crossing the road, to hailing a taxi, from consuming a McDonalds (“Fries are pomme frites!” – some silver presumably crossed Meyer’s hands to show the novelist chomping down thrilled on the fast food chain’s merchandise) to working out the rate of exchange for his fifteen Victorian pounds doesn’t translate to many dollars, it’s got a fish-out-of-water delight and a shrewd comic energy.

It’s helped a great deal by McDowell’s gentle, playful and thoroughly engaging performance – Time After Time leaves you sad he doesn’t get to play more roles like this. Wells is optimistic, polite, gentlemanly and admirably brave: even more so, because he’s so hesitant about risk. He travels around the 1970s with a wide-eyed wonder and has a humanitarian streak a mile wide. He’s one of the nicest guys you could meet.

No wonder Amy falls for him so swiftly. There is an electric chemistry between Mary Steenburgen – full of Southern sweetness but with a very modern (but never grating) feminism – and McDowell (and clearly off screen as well, as they married almost immediately after). Meyer plays this romance like a classic rom-com, with meet-cutes at the bank and McDowell’s playing of this shy Victorian gentleman’s courtly manners (he touchingly stops a kiss to make absolutely sure he has full consent – which Amy makes clear he more than does!) works like a charm.

The jokes are genuinely well-thought out and keep the film brisk. I love the alias Well’s plucks out of the air when pretending to the police to be a Scotland Yard detective: he seizes upon what he guesses will be a long forgotten popular fiction character of his day and calls himself Sherlock Holmes. McDowell and Steenburgen have an affinity for physical comedy – watch McDowell hail a taxi with a jaunty wave or Steenburgen sitting frustratedly on a sofa waiting for Wells to make a move. The fish-out-of-water elements work a treat (you can see the clear groundwork for gags Meyer would take even further in his next time-travel hit Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home).

Time After Time sits this comedy next to a genuine Ripper-flick. The film opens with a long POV shot as the Ripper strikes in the streets of London. David Warner gives a very good performance as a world-weary psychopathic, who can hide his depravity but not control his urges. Unlike Wells, the Ripper adjusts very naturally to the modern world – probably because he’s more used to pretence than the honest Wells – dressing in progressively more relaxed 70s garb. His murders are shot with discretion – mostly off screen with the inevitable splash of scarlet on a surface or face from off camera. The actual historical elements of the Ripper are bunkum, but the handling is well done.

The time travel elements are rather laboriously explained, with much talk of keys, return-prevention locks and stabilisers. Wells points out the various features of the machine with a bluntness that all but has Meyer tapping you on the shoulder and saying “remember that it will be important later” – you can utterly (correctly) guess the eventual ending purely from this lecture. But the time travel effects use a mixture of 2001-ish camera tricks rather effectively and the film plays a little bit with paradox and timeline tweaking (although without any depth).

Meyer’s film is an enjoyable ride, even if some plot developments gear shift swiftly (the Ripper seems to have had a sudden emotional breakdown at some point between his penultimate and final scene and the reasons for the time machines physical shift to San Francisco are barely explained) and it at times loses its drive (the Ripper is all-too-obviously presumed dead at one point and his determination to grab a key that controls the time machine oscillates with urgency from act to act). But as a debut, it’s an enjoyable piece of pulp. And it’s got a hugely likeable performance from McDowell and very assured support from Steenburgen and Warner. It’s a very enjoyable romp.