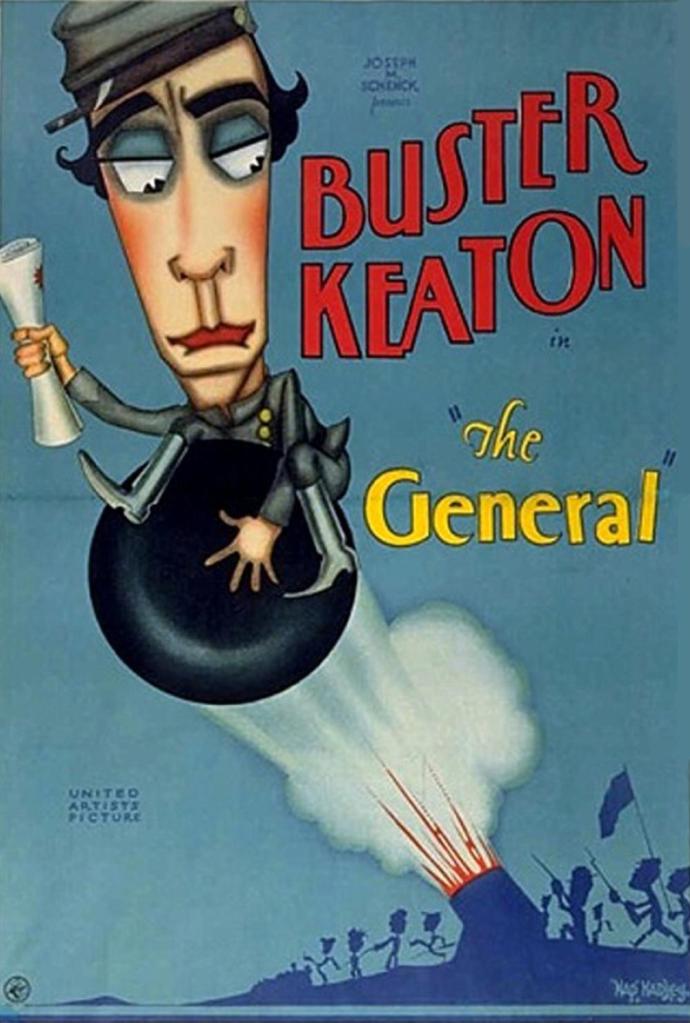

Keaton’s masterpiece, less of a comedy and more an inspiration for hundreds of action films

Director: Buster Keatson & Clyde Bruckman

Cast: Buster Keaton (Johnnie Gray), Marian Mack (Annabel Lee), Glen Cavander (Captain Anderson), Jim Farley (General Thatcher), Frederick Vroom (Southern General), Charles Smith (Mr Lee), Frank Barnes (Annabel’s brother), Joe Keaton (Union General)

The General frequently features in the lists of greatest comedies of all-time. It’s a bit of a misnomer: while The General has its fair share of jokes, it’s really a sort of action film. A Mad Max: Fury Road with gags, the greatest chase you’ll ever see and one of the most dynamic stunt spectaculars ever made. It’s Keaton’s apogee, one of the most influential and greatest films ever made. If you’ve ever seen a stunt-filled epic, you’ve seen something that takes inspiration from the tireless physical tricks Keaton pulled here and the stunning, cinematic grace he films it with. The General is a classic that is instantly, and constantly, rewarding.

Keaton plays Johnnie Gray, a respected engine driver of the South with two loves in his life: Annabel (Marian Mack) and his steam engine The General. He’s about to propose to Annabel when the Civil War breaks out. She wants him to enlist: he tries his best but is rejected, unbeknownst to him, because the army considers him more valuable as a train driver. Mistakenly seen as a coward by Annabel, she vows never to speak to him again. A year later The General is hi-jacked by Union soldiers as part of a surprise offensive. Johnnie gives chase in a second engine, The Texas, unaware Annabel is aboard the kidnapped General. The wild chase takes Johnnie North then South again to bring Annabel home and report to the Confederate army the approaching attack.

The General was the most expensive film Keaton’s company had ever made. No expense was spared in bringing two period-accurate engines to the screen, with everything shot in location (in Oregon, admittedly, due to the Tennessee not being keen on staging a Civil War Keaton comedy) and all executed in perfect period detail. The film contained the most expensive single shot ever mounted – costing a whopping $42,000, it would show a real bridge collapse and hurl a real engine into a real river (Keaton filmed in long shot, with real horses moving around near the bridge, to stress this was a real stunt not a model). Despite all this, the film was a box-office disappointment.

Why? Well frankly, I’m not sure the world was ready for something that promised itself as being a comedy set during what was still a raw scar in the American psyche. The marketing material also promised more laughs than you can shake a stick at – a misrepresentation of a film that is more a stunt-filled poem than a slapstick riot. For those expecting The Navigator, The General was a disappointment. For us today, it is one of the great American films, a piece of cinematic mastery.

The General is for a large chunk of its run-time (almost 40 of its just under 80 minutes) a glorious chase, in which every sequence show-pieces invention at high-speed. The majority of the stunt filled tricks were executed by Keaton himself, surely at some considerable risk to life and limb. As you watch him bound over railway carriages, dive through port holes, sprint alongside steaming trains or sit atop the hurling railway sleepers to remove obstructions, you can only marvel at his physical dexterity and commitment.

Keaton’s character is also subtly, and impressively, different from his other roles. These were often defined by their haplessness – would-be detectives and empty-headed heirs. But within his professional sphere, Johnnie is a master. He knows the capabilities of engines and dynamics of the railroad better than anyone. He is relentless and endlessly inventive in overcoming myriad problems just as he can use his knowledge to place near-insurmountable barriers in the way of his pursuers.

The opening of the film stresses the respect people hold him in – he’s hero-worshipped by children, greeted warmly by all and has no doubts about asking Annabel to marry him. Sure Johnnie can get pre-occupied and miss the bigger picture – a few times, he is almost left behind by the steaming train while resolving problems on the line – and away from the train, especially when he joins the soldiers in the film’s finale, he suffers from the same clumsy, cluelessness as Keaton did fighting to defend his ship in The Navigator. But he’s also brave, indefatigable, ingenious and relentless. He’s more of a model for every action hero maverick since than you could imagine.

And those stunts! Keaton was a master film-maker, framing the action to accentuate its speed, scale and reality. The camera runs alongside the train, demonstrating its speed by showing objects move by. The action is frequently framed in medium and long shot to demonstrate its scale and the grandness. This goes for Keaton bounding across carriages and for simple gags, such as the famous shot of a forlorn, jilted Johnnie sitting on a drive rod of the moving train, lifted up and down as it shunts forward. The complexities of this chase are always made clear and camera angles are key to the various attempt each train makes to stop the other. This is placed above the standard comedic reaction close-ups audiences expected – but make for a richer, more rewarding film.

In fact, watching the film, you can grow to admire Johnnie so much you start to wonder what he sees in Annabel. Perhaps Keaton, to an extent, wondered the same. Annabel is kidnapped, tied up, caught in a bear trap, tossed around in a sack and doused in engine water. Is this woman being partially punished by the film? After all, it’s her demand that Johnnie turn his life upside down to fight in (what we know) will be a brutal war – and her kneejerk condemnation of him – that sets events in motion. Does she need this humbling to learn her lesson? It perhaps helps her and Johnnie become an ever more effective partnership on their flight back South, setting traps and keeping the engine going (with the odd comic misunderstanding, one of which sees Johnnie running down then back up a hill to reboard the train) that leads to their eventual reconciliation.

Interestingly, what’s less comfortable with The General today is its avoidance of the core issues of the civil war. Slavery never rears its head, and the film takes a largely sympathetic view of the romantic Southern gentlemen vs the nefarious Northerner, with their under-hand schemes. Peter Kramer, in an excellent BFI book, lays out a compelling argument that The General exposes, especially through its final battle sequence which sees real people die and a hapless Johnnie charging into heroics like a lost child, the dangerously blind embrace of violence in the South and a subtle criticism of a horrific war that led to so many needless deaths. While there might be beats of that under the surface here (especially if you are familiar with the shocking death toll of the war), it’s not enough to overcome the generally sympathetic view of the Confederacy and its leaders.

But politics is not at the heart of Keaton’s film. The appeal for him, just as for Johnnie, was that engine and, by extension, the glory of the chase. Only someone who loved trains as much as Keaton could have made such a guilty pleasure of plunging one thirty feet to its doom on camera. And in Johnnie Flynn he created a genuinely little-guy hero, a character who shared his dynamism and pluck and, above all, his love for all things mechanical.

The General isn’t a comedy really – there are few real belly laughs in it, and the film is played straight by all and sundry, devoid of reaction shots. Its laughs come in shock at its audacity, its epic scale and from how much it causes you to invest in the trials and tribulations of its lead character. It’s an action film that you embrace with fervent love, because it’s pure, unadulterated, cinematic beauty. It’s a masterpiece.