The franchise closes on a high with a fun, romantic and exciting finale, tonnes better than Part II

Director: Robert Zemeckis

Cast: Michael J. Fox (Marty McFly/Seamus McFly), Christopher Lloyd (Emmett “Doc” Brown), Mary Steenburgen (Clara Clayton), Thomas F. Wilson (Biff Tannen/Buford “Mad Dog” Tannen), Lea Thompson (Lorraine McFly/Maggie McFly), James Tolkan (Marshal James Strickland), Elizabeth Shue (Jennifer), Matt Clark (Chester), Richard Dysart (Salesman), Flea (Needles)

And we’re back. After the frankly awful Back to the Future Part II – an onslaught of bad gags, terrible performances, clumsy call-backs and a lot of sound and fury – the trilogy ended on a high with Back to the Future Part III which, by going back to the past, managed to find more heart and originality than Part II ever had. Strangely, by looking backwards in time, the series managed to look forward to new ideas. Part III is, by many degrees, a huge improvement.

We left Part II with Doc Brown (Christopher Lloyd) stranded in 1885 and Marty McFly (Michael J Fox) equally stranded in1855. How are they going to get back to 1985? Well Doc is happy where he is, and has left the Delorean buried in 1885 for Marty to dig it up in 1955 and get back to the future with the help of the 1955 Doc. But, digging the Delorean up, Marty discovers Doc’s 1885 grave: turns out he will be murdered by gunslinger Buford “Mad Dog” Tannen (Thomas F Wilson). So, Marty travels back to 1885 to save him. But with the Delorean damaged on the way, how will they get back to 1985? Will Doc or Marty be killed in a fatal gunfight with Tannen? And what about the Doc and schoolteacher Clara Clayton (Mary Steenburgen) falling in love?

Back to the Future Part III juggles all these plot themes with real expertise, all based in a hugely affectionate portrait of the Old West that drips with Zemeckis and Gale’s childhood love for the genre. I’m going to guess that Part III is inexplicably not held in the same regard as Part II because my generation and onward simply has far less of a connection to the Western than they do crudely cheesy views of an 80s tinged future.

But the sense of fun here is on point. Galloping horses, street fights, open air dances, trains, cameos from old-school Western supporting actors, the majestic score… it’s all an on-point reconstruction of the tone and style of Ford. (In particular, the entire film feels like a fun recreation of many elements of My Darling Clementine). The film also has fun with later perceptions. Marty is dressed up for his journey back to 1885 in the sort of brightly coloured, skin-tight costumes 1950s TV and B-movie western stars wore. He adopts the alias “Clint Eastwood” (and doesn’t the film have fun with that). He even (eventually) dresses not dissimilarly from the Man with No Name himself.

It doesn’t stop with the Western re-build. Back to the Future Part III has the inevitable call-back gags to events we have seen throughout the last two movies. But here they are delivered with a far more freshness. Not least because Doc and Marty largely reverse roles here (leaning into this, they even swop their catchphrases at one point). While in the previous films Marty was the impulsive one, flying by the seat of his pants with instant decisions and being assisted by the eccentric Doc, here they settle into new roles.

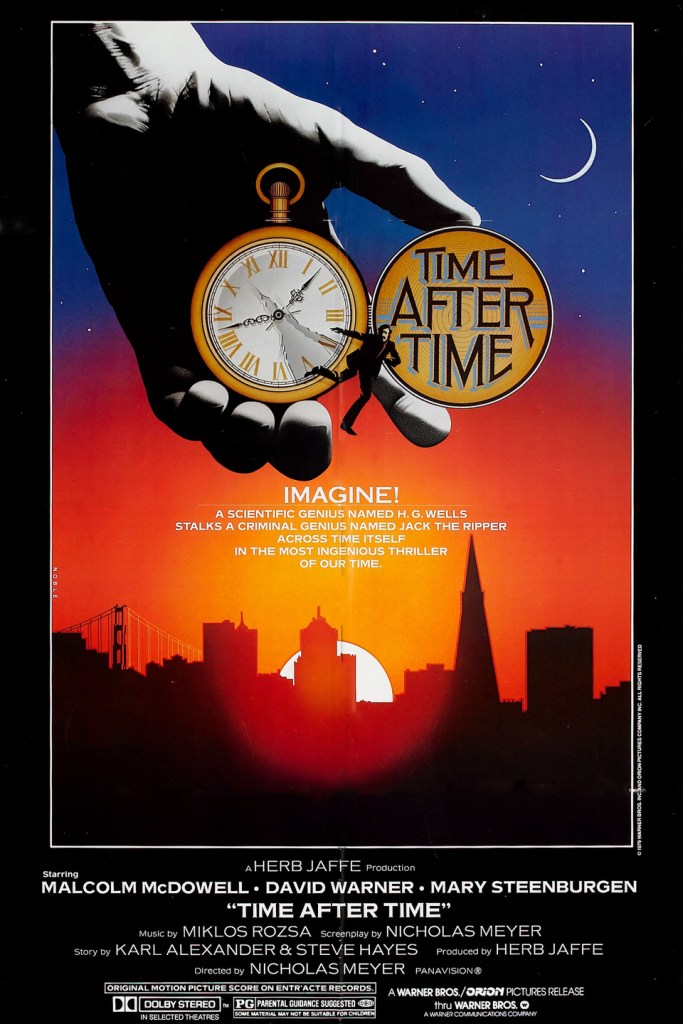

Because Doc here is the one being rescued and the one tempted by an impulsive decision. Namely, staying in the past because he has fallen in love. Christopher Lloyd, a much better actor than he gets credit for, is allowed to broaden out and enrich his eccentric performance as Doc with a real emotional depth in a very sweetly drawn romance. Mary Steenburgen is equally good as the kindred spirit he falls in love with. Both actors play the romance dead straight and it allows Lloyd to show an emotional depth and shade his performance has lacked elsewhere. Steenburgen’s casting is also a nice tip-of-the-hat to Time After Time (where she also played a woman who inadvertently falls in love with a time traveller). Clara is also a neatly written character, integrated far more into the plot than poor Jennifer in Part II and another welcome shake-up the buddy formula.

As Doc takes on the romantic and paradox creating role, Marty becomes the driver, urging Doc to stop getting mixed up in influencing past events and focus instead on fixing the Delorean and getting back home. Fox embraces playing (largely) the secondary role in the film. He still gets moments of fun as an actor (not least playing Marty’s Irish great-grandfather – a performance immeasurably better than all his latex covered efforts in Part II) but he’s largely the voice of sense here.

Except of course concerning his fatal character flaw: don’t call him chicken. There is nowhere more dangerous to allow someone to pick a fight with you than the Wild West. And Marty swiftly inherits the clash with Tannen (played with gruff comic gusto and impenetrably density by Thomas F Wilson). This culminates – but of course – in a face-off in a dustbowl street, with a solution to the gunfight inspired by the real Eastwood and nicely signposted in Part II.

That leads into a genuinely edge-of-the-seat exciting race to hijack a train to push the Delorean up to the desired 88 miles an hour. Zemeckis shoots and cuts this sequence to perfection – and Alan Silvestri’s score does a lot of build and sustain the tension and excitement – and it seems appropriate that the only real opponent Marty, Doc and Clara have to deal with in this sequence is time itself. Crammed with sight gags, orchestrated to perfection and perfectly paced it’s a great way to cap the series.

Much as the film itself is a perfect ending to the franchise. Its imaginative and playful, riffing on the previous events without slavishly imitating them, approaching both its characters from new angles that helps us discover new things about them and crammed with great jokes, exciting set-pieces and genuine emotion. It’s easily the second-best film in the franchise. If you want to revisit a sequel for Back to the Future do yourself a favour and pick the one in the past.