Visconti’s grand tale of romantic obsession is an engrossing film to lose yourself in

Director: Luchino Visconti

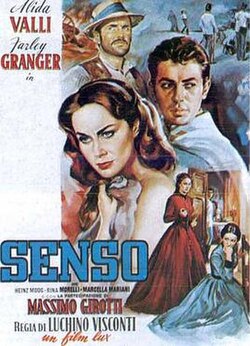

Cast: Alida Valli (Livia Serpieri), Farley Granger (Franz Mahler), Massimo Girotti (Roberto Ussoni), Heinz Moog (Court Serpieri), Rina Morelli (Laura), Christian Marquand (Bohemian official), Sergio Fantoni (Luca)

It probably felt like a real shock when Visconti made a sharp turn from neorealism into luscious costume drama. But, in a way, isn’t it all the same thing? After all, if you wanted to get every detail of a peasant’s shack just so, wouldn’t you feel exactly the same about the Risorgimento grand palaces? So, it shouldn’t feel a surprise that Visconti moved into such stylistic triumphs as Senso – or that an accomplished Opera director made a film of such heightened, melodramatic emotion as this. Chuck in Senso’s political engagement with the radicals fighting for Italian independence, and you’ve got a film that’s really a logical continuation of Ossessione.

Set in 1866, the rumblings of unification roll around the streets of Venice – the city still under the control of the Austrian empire, despite the city’s Garabaldi-inspired radicals. In this heated environment, Countess Livia Serpieri (Alida Valli), cousin of radical Roberto (Massimo Girotti) finds herself falling into a deep love (or lust?) for imperiously selfish Austrian officer Franz Mahler (Farley Granger). It’s an emotion that will lead her to betray everything she believes she holds most dear and lead to catastrophe.

It’s fitting Senso opens at a grand recreation of La Traviata at the Venetian Opera. Not only was Visconti an accomplished director of the genre, but as Senso winds its way towards its bleakly melodramatic ending, it resembles more and more a grand costume-drama opera, with our heroine as a tragic opera diva left despairing and alone, screaming an aria of tormented grief on Verona’s streets. You’ll understand her pain after the parade of shabby, two-faced treatment the hopelessly devoted Livia receives at the hands of rake’s-rake Franz, a guy who allows little flashes of honesty where he’ll confess his bounder-ness between taking every chance he can get.

What Senso does very well is make this tragic-tinged romance so gorgeously compelling, that you almost don’t notice how cleverly it parallels the political plotlines Visconti has introduced into the source material. Because Franz’s greedy exploiting of Livia for all the money he can get out of her, the callous way he’ll leave her in dire straits or the appallingly complacent teenage rage where he shows up and inserts himself into her country palace (with her husband only a few rooms away) is exactly like how Austria is treating the Italians, stripping out their options, helping themselves to what they like and imposing themselves in their homes.

Livia’s besotted fascination with Franz kicks off at the same opera where the Garabaldi inspired revolutionaries disrupt events by chucking gallons of red, white and green paper down from the Gods onto the Austrian hoi-polloi. And their destructive relationship will play out against an outburst of armed revolutionary fervour, both of them stumbling towards a dark night of death and oppression in the occupied streets of Verona. Livia’s obsession will damage not only herself, but these same revolutionaries who be left high-and-dry when Livia prioritises Franz’s well-being over the revolution’s survival, by funnelling the gold she’s concealed for the purchase of arms into Franz’s wastrel pockets.

But it’s impossible to not feel immensely sorry for Livia, because her desperation and self-delusion is so abundantly clear. Alida Valli is wonderful as this woman who only realises how lonely she is when she finds someone who can provide the erotic fire her detached, self-obsessed husband never has. It’s a brilliantly exposed performance: Valli actually seems to become older as time goes on, as if collapsing into the role of wealthy sugar-mummy to an uncaring toy boy.

Before she knows it, she will be wailing that she doesn’t care who knows of her feelings, before dashing across town to where she believes Franz is staying (it turns out instead to her revolutionary cousin, her husband assuming her feelings are revolutionary sympathies not infidelity). She knows – God she clearly knows! – Franz is not worth the love she is desperately piling onto him, but her need for him is so intense, that we can see in her eyes how desperate she is to persuade herself otherwise. Valli sells the increasingly raw emotion as she can no longer close her eyes to Franz’s selfishness and cruelty and her final moments of raging against the dying of her light are riveting.

Opposite her, Farley Granger (dubbed) may not have enjoyed the experience (he refused to come back and film his final scene, which was shot instead with a partially concealed extra) but his selfish youth and cold-eyed blankness is perfect for a man who cares only for himself. There are parts of him that need to be mothered, and he’s not above throwing himself on her covered in gratitude. Sometimes he’ll advise her he’s not worth it, or sulk like a petulant kid if he feels he isn’t getting enough attention. But he’ll always come back for more wealth.

His shallow greed is appalling. His eyes light up when Livia gives him a locket with a lock of her hair in it. Sure enough, she’ll find that hair discarded in his apartment when she searches him, the locket sold. His fellow soldiers know all about his roving, careless eye – he’s “hard to pin down” one knowingly says, so clearly indicating Franz’s lothario roaming that it’s hard not to feel desperately sad for Livia. The vast risks she takes for him, he’ll chuck away on the next shiny thing (or woman) to catch his eye. But he can also be charming or vulnerable – or at least fake these qualities – so well that Livia continues to persuade herself he is someone she can ‘save’ from his flaws.

It leads to disaster for all, a personal tragedy swarming and soaking up thousands of others. Her revolutionary cousin Roberto will be collateral damage, Visconti capturing this in two exquisitely staged battle sequences (one utilising a stunning near 360 camera turn to take in the catastrophic after-effects of a failed advance by the revolutionaries). This is the grand destruction that wraps around the Operatic failed romance at the height of Senso: it’s a sign that the all-consuming lust that consumes its lead has reached out and crushed almost everything around it.

It makes sense then that the luscious colour and gorgeous design of Visconti’s film comes to its conclusion in dreary streets, nighttime confrontations and a final mood that feels nihilistic and destructive. Senso is a wonderful exploration not only of the senseless destruction of romantic obsession, but also of the wider damage where this negative energy shatters a host of high-flown, optimistic political ideals leaving only ruins and disaster behind. Visconti’s masterful balancing of all of this makes Senso a shining example of both gorgeous film-making and a wonderful mix of compassion and the high-blown. A wonderfully engrossing film to soak in.