An almost undefinable mix of gangster and philosophy, almost unique in its eccentric oddness

Director: Donald Cammell, Nicolas Roeg

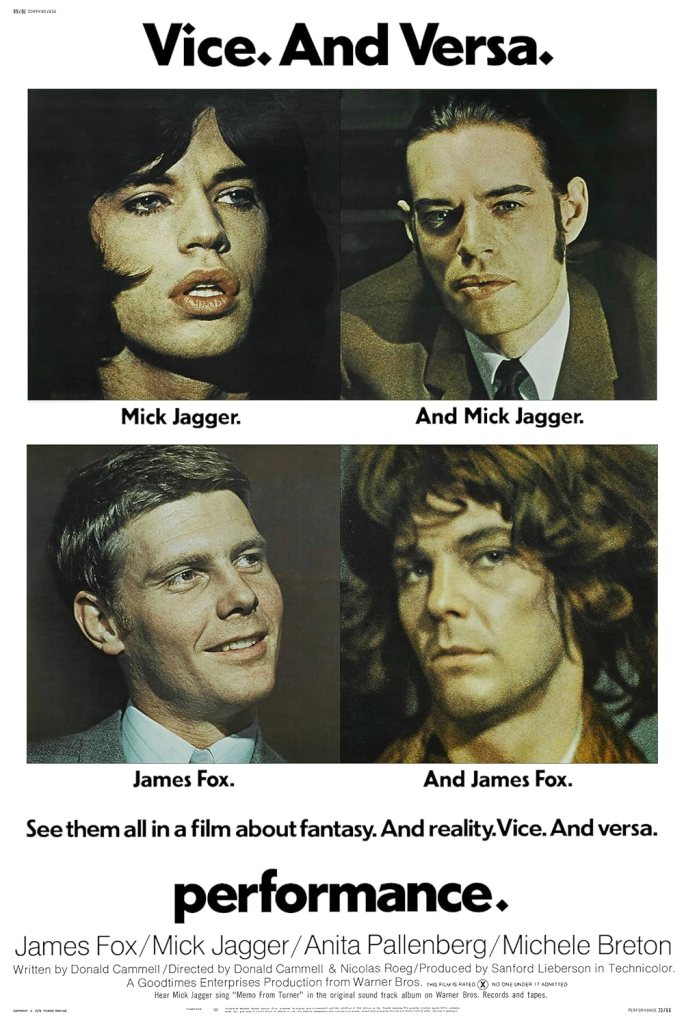

Cast: James Fox (Chas), Mick Jagger (Turner), Anita Pallenberg (Pherber), Michèle Breton (Lucy), Ann Sidney (Dana), John Binden (Moody), Stanley Matthews (Rosebloom), Allan Cuthbertson (Lawyer), Anthony Morton (Dennis), Johnny Shannon (Harry Flowers), Anthony Valentine (Joey Maddocks), Kenneth Colley (Tony Farrell)

Performance seems to slop out of the swinging sixties dark side, a brash and darkly disturbing explosion of style and intellectualism. There are few films like it out there: its a sometimes tough but haunting watch, crammed with mind-bending imagery and swimming in strange and unsettling ideas. It’s both a gut punch and an unsettlingly erotic massage.

Chas (James Fox) is a ruthless gangland enforcer for mob boss Harry Flowers (Johnny Shannon). Ambitious but instinctively violent, he’s a slim, tall cocktail of anger and predatory resentment – so it’s not a surprise that he eventually provokes a minor gangland dust-up, which leads to him killing a rival against Harry’s orders. His life in danger, Chas retreats to a convenient bolthole. Passing himself off as a travelling juggler (!), he wheedles his way into the home of reclusive pop star Turner (Mick Jagger) who lives a life of philosophy, drugs and free love in a beat-up house in Notting Hill. There Chas and Turner will form an unusual connection as a mixture of drugs and repressed yearnings and longings see their personalities begin to mix and merge.

It was born from the mind of Donald Cammell and was originally commissioned as a sort of 60s romp. Many of the money men signed on, under the impression they would be getting a sort of A Hard Day’s Night for The Rolling Stones. God alone knows what they made of the nightmare fuel they ended up (rumour has it, the wife of one executive vomited at an initial screening). Cammell, heavily influenced by Jorge Luis Borges, created a dak dream-like work where questions of identity and sex get wrapped up in a surreal framework where reality bends around the crazy logic.

It’s reflected in the film’s artistically discordant style, re-edited to deliberately blur linear lines and (increasingly) tip the film into dream-like logic. From the opening ten minutes we start switching between different, complementing, tones. In this case between Chas and his cronies in a car and a stereotypically upper-class lawyer (Allan Cuthbertson at his most imperial) speaking in court to a pompous jury who themselves merge with the dirty-old men watching a cheap porno flick in one of Chas’ stopping points.

This surrealistically toned cutting – married to strikingly beautiful, unusual colour-filled lighting from Nicolas Roeg (who co-directed the film with Cammell, delivering much of its visual look) – lays the groundwork for a film that increasingly shifts into something strange and constantly unsettling, where we can never be quite sure where we are. Characters merge into each other, brief cuts showing Jagger switch places with Fox and Pallenberg (at one point Chas and Turner appear in bed together before Turner is replaced in the next cut with Lucy), sequences take place that must be fantasy and the real-world disappears in a finale that lays the entire film open to interpretation.

What’s striking about Performance is that, even with stylistic flourishes, much of the opening section plays like a hard-boiled gangster film. There is a marked reality about Chas’ moving around the streets of London, roughing up taxi firm owners, threatening rivals and intimidating the loose lipped. Surprising as it might seem, it reflects Chas’ conservativeness: a self-made man, Chas takes inordinate pride in his freshly-cut suits and perfect hair, lives in a flat that’s like an interior design brochure and has contempt for arty free-spirits. The film’s opening matches his everyday aesthetic.

He’s played with a snarling aggression by James Fox, a hugely successful piece of counter-intuitive casting. Fox makes Chas tense, cocky and no-where near as clever as he thinks he is. He’s a bully who delights in terrifying a posh chauffeur and resents taking orders. He’s vain– his apartment littered with glossy photos of his own half-naked athletic body – and his sadomasochistic sex with his girlfriend is carried out with hand-held mirror so he can watch himself. This is a rich, primal, brilliant performance by Fox, latching into a dark energy he rarely touched again.

What’s also striking though is that there is a vulnerability and emptiness to Chas. Odd as it might seem, it’s also a mirror-image of Fox in The Servant: there a naïve young man absorbed by his butler – here a seemingly worldly gangster, totally unsettled and slowly changed by a new domineering force in his life. Chas may believe himself to be the master, but he’s a rat in a maze in the psychedelic craziness of Turner’s world, with a freedom, wildness and gentleness completely alien to Chas’ ordered world.

Whipper-thin and with a natural charisma that almost masks his fundamental weakness as an actor, Jagger sashays into the film as a softly spoken force of nature, the sort of artist who pops pills then reads philosophy. His house, all ramshackle opium den chic, is a hedonistic place of relaxed freedoms where Turner lives in a menage with Pherber and Lucy (there was much scandal at the time about whether Jagger and Pallenberg had sex for real during filming). It’s a surrealist den, shot from unusual or unsettling angles with an oddly precocious child (whose gender seems to change from scene to scene) running around.

Turner finds Chas fascinating – and it’s here the film’s title comes to life as Cammell muses how much is Chas’ personality an affectation, a construct that he has built? Doped up on magic mushrooms, Turner (and the film) explore and deconstructs the sort of man Chas is. From Turner dressing-up as and impersonating Chas, to Chas himself stripping down physically and mentally, both in the sort of bohemian clothes he despised and even trying on feminine garb with face paint. It unpeels the construct of Chas hyper-masculinity to find a more tender, less egotistical man below.

And what better construct, you might argue, than gangsters? These are people living an eternal front (Flower’s office is awash with brash touches – like an equestrian painting of himself – that hide his closeted and violent nature; he’s clearly inspired by both Krays). It’s a front the openly hedonistic and relaxed Turner can shake up: Jagger sings ‘Memo From Turner’ in a surreal dreamish sequence, where he takes Flowers place and encourages his fellow gangsters to literally strip. Performance deconstructs this, using editing to merge Turner and Chas, as two sides of the performance coin.

The film spirals further down this rabbit hole of personality shifting, as Chas becomes more and more like the softly waif-like Turner, just as Turner experiments with the flouting masculine aggression of Chas. Mirrors allow us to visually mix and merge characters and strange cuts take us on an increasingly non-linear journey. This remains unconfirmed and undefined – one critic wrote it was easier to write a book about Performance than a review and he’s probably right – and the further down this metaphorical (and, in its final sequence, almost literal) rabbit hole you go, the more the surreal questions remain unanswered. What is going on in the end? Is it real? Who absorbs who? All questions remain enigmatically open and rife to multiple interpretation.

Performance is hardly an easy watch. I can easily imagine the wrong person at the wrong time finding it either disturbing or (probably more likely) a pile of pretentious wank. But it’s a daring, undefinable and unreadable film that offers itself up to ripe interpretation and re-interpretation while remaining playful. And that is one heck of a difficult performance to pull off.