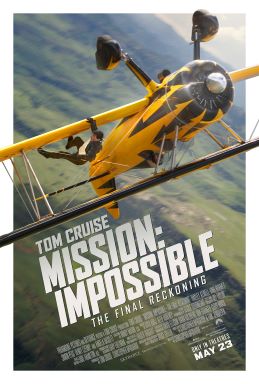

Cruise’s final mission is really a tribute to the star himself and his never-ending force of will

Director: Christopher McQuarrie

Cast: Tom Cruise (Ethan Hunt), Hayley Atwell (Grace), Ving Rhames (Luther Stickell), Simon Pegg (Benji Dunn), Esai Morales (Gabriel), Pom Klementieff (Paris), Henry Czerny (Eugene Kittridge), Angela Bassett (President Erika Sloane), Holt McCallany (Serling Bernstein), Janet McTeer (Secretary Walters), Nick Offerman (General Sidney), Hannah Waddingham (Rear Admiral Neely), Tramell Tillman (Captain Bledsoe), Shea Whigham (Briggs), Greg Tarzan Davies (Theo Degas), Charles Parnell (Richards), Mark Gatiss (Angstrom), Rolf Saxon (William Donloe), Lucy Tulugarjuk (Tapeesa)

Almost thirty years after the first film trotted into the cinema, Tom Cruise signs off (he claims) his franchise of death-defying stunts with a final entry that dials the global threat up so far you can almost hear the desperate whirring as the doomsday clock tries to keep up. Mission: Impossible: The Final Reckoning is big in every single way, packed with set-pieces, dense procedural plot mechanics that require reams of exposition, global annihilation round every corner and at the centre the towering, chosen-one aura of Ethan Hunt himself, the only man who can save the world.

The Final Reckoning takes off a few weeks after the now-rechristened Dead Reckoning (after it under-performed they didn’t want to scare people off with a Part 2 subtitle). AI demigod The Entity is hellbent on gaining control of the world’s nuclear arsenals so that, having presumably binged Terminator, it can SkyNet-like wipe out humanity. Ethan (Tom Cruise) is on the run, but he has a plan. Dig out the sunken Russian sub where the Entity was ‘born’, fish out its source code, hook it up to an Entity-killing virus and trap the AI would-be-overlord in what’s essentially a glowing USB drive. This mission will involve lots of running, fighting, defusing of nukes, diving to the bottom of the ocean, jumping between bi-planes mid-flight… he might as well chuck the kitchen sink as well.

Mission: Impossible: Final Reckoning has plenty of fun, even if it is hellishly overlong. It’s the sort of crowd-pleaser that gets people clapping at the end (as several people in my packed-out screening did). When the stunts come, they’re hugely well-staged. As always the Tom Cruise USP is front-and-centre: if you see him do it, he did it. Yes, Tom really did jump out of a naval helicopter into the raging Atlantic. Yes, that really is Tom, climbing over a speeding bi-plane thousands of feet-up with only a pair of goggles to keep him safe. It’s no-coincidence the villain is an AI who creates an artificial digital reality. The Mission: Impossible films are all about it keeping it solidly real.

But, once the initial adrenaline rush subsides, I’m wondering if its pumped-up thrills are going to be a bit more wearing second-time around. What struck me about The Final Reckoning is, that for all the huge amount of stuff going on, there is precious little heart in it. More than any other M:I film since the little-loved M:I:2 (practically the only film in the franchise not to get a shout-out here), the act of saving-the-world here is a job for one never-wrong superhuman. Cruise does almost everything, his team’s main role being getting into the right place to send him a message or wire up a computer. On top of that, the best of the series set-pieces had flashes of Ethan’s stress, fear and sense of ‘I cant believe I have to do this’ humour – all of that is mostly missing here.

The Final Reckoning loses a lot of the heart of what made the earlier films so rewarding. It loses the moments of friendship or sparky interplay between the team. Cruise and Pegg, the series main comic relief, share almost no scenes together. Klementoff and Davies do virtually nothing as new team members, other than shoot guns and get captured. Cruise shares more time with Atwell, but the bizarre is-it-a-romance-or-not between them is as oddly undefined as Ethan’s relationship with Rebecca Ferguson’s Elsa was (in fact it makes you realise the most sexual thing Ethan has done since film three is hold someone’s hand). Cruise is so often on solo missions, that the film could probably have dispensed with the team altogether with only a small plot impact.

The film only affords to slow down to give Ving Rhames (the only other guy to appear in every film) a moment of genuine emotion – though special mention must go to Rolf Saxon and Lucy Tulugarjuk who from small moments craft characters I genuinely grew attached to and worried about. Otherwise, the bonds of friendship that powered the franchises most successful non-stunt moments are absent. In fact, also missing are the heist caper set-pieces – even the famous face-masks are only employed very briefly.

The Final Reckoning dials the stakes up so much, they are effectively meaningless. In previous films, high-stakes were mixed with personal ones: we were always more invested in whether Ethan save his friends rather than the word. The film also struggles without a real antagonist. Its nominal human opponent, Esai Morales’ Gabriel, little more than a smirk and an obstacle. Shorn of the most-interesting element of his character – his fanatical loyalty to his AI master – Gabriel is neither particularly interesting or a threat. In its vast runtime, Final Reckoning has no time to actually explore what the personal link between Ethan and Gabriel actually was, making you wonder why on earth they bothered to put it in both films in the first place.

It’s not helped by the fact that the film is so constantly in motion, that virtually every single scene of dialogue is about communicating what’s going to happen next. There are constantly (admittedly skilfully batted around) conversations explaining why Ethan has to go there, get this, bring it here, do this to it, put it in that all within a ridiculously small window of time. Sometimes, to shake it up, we cut across to the US bunker where a gang of over-qualified actors (Bassett, Offerman, McCallany, McTeer and Gatiss) similarly explain what the Entity is doing to each other. (Although, like Rhames, Bassett gets the most interesting stuff to actually act as a President facing a Fail Safe like terrible choice).

What you realise is that The Final Reckoning is pretty confident that what really pulls the audience in is Tom Cruise doing crazy stunts, so that’s what it gives us. In fact, rather than a tribute to the series (despite closing plot points from Missions 1 and 3) what the film really feels like is a tribute to Cruise, the last man-standing among the old-fashioned superstars. Most of the dialogue puffs up Cruise’s Ethan into Godlike status (it’s not quite “living manifestation of destiny” like Rogue Nation put it, but close). Cruise carries out two extended fight scenes in his pants (though if I looked like that at 61 so would I). No other actors intrude on his stunts or messianic sense of purpose.

Which is amazingly done of course. Literally no-one does it better than Cruise. The fact that the movie feels like Cruise effectively shot most of it alone with just the crew, means it almost doesn’t matter that its plot is merely to link together set-pieces. And if someone deserves a victory lap – which is what this is – then that guy is Cruise. I’d have wanted more of the fun, humour and warmth that made most of the other films such massively rewarding hits. But The Final Reckoning gives more of what the series does that no other series does. And I guess that’s a fitting finale.