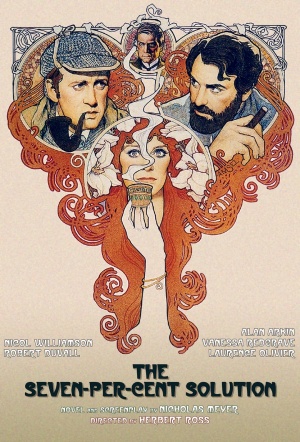

Affectionate and faithful Holmes pastiche that shines an interesting light on the Great Detective’s character

Director: Herbert Ross

Cast: Nicol Williamson (Sherlock Holmes), Robert Duvall (Dr John Watson), Alan Arkin (Dr Sigmund Freud), Laurence Olivier (Professor Moriarty), Vanessa Redgrave (Lola Devereaux), Joel Grey (Lowenstein), Jeremy Kemp (Baron Karl von Leinsdorf), Charles Gray (Mycroft Holmes), Samantha Egger (Mary Watson), Jill Townsend (Mrs Holmes), John Bird (Berger), Anna Quayle (Freda)

The magic of Sherlock Holmes is he is immortal. Doyle’s detective has been reshaped so many times since the publication of the canonical stories, that we’re now used to seeing him presented in myriad ways. It was more unsettling to critics – particularly British ones – in 1976, who didn’t know what to make of an original, inventive Holmes story that treats the characters seriously but is playful with the canon. Was this a parody or a new story? (Why can’t it be both!) Today though, The Seven-Per-Cent Solution stands out as a Holmesian treat, a faithful slice of gap-filling fan fiction.

Based on a best-selling novel by Nicholas Meyer (who also adapted it), The Seven-Per-Cent Solution expertly reworks Doyle’s The Final Problem. Professor Moriarty (Laurence Olivier) is not the Napoleon of Crime, but a mousey maths tutor, the subject of Holmes’ (Nicol Williamson) cocaine-addled idée fixe. Worried about his friends dissent into addiction, Dr Watson (Robert Duvall) tricks Holmes into journeying to Vienna to receive treatment from an up-and-coming specialist in nervous disease and addiction, Dr Sigmund Freud (Alan Arkin). The treatment is a slow success – and the three men are drawn into investigating the mysterious threat to drug addicted glamourous stage performer Lola Devereaux (Vanessa Redgrave) that may or may not be linked to her fierce lover, the arrogant Baron Karl von Leinsdorf (Jeremy Kemp).

As all we Holmes buffs know, seven per-cent refers to Holmes’ preferred mix of cocaine, taken to stimulate his brain between cases and see off boredom. But what if that persistent cocaine use wasn’t a harmless foible – as Holmes tells the disapproving Watson – but something much worse? Kicking off what would become a decades long obsession with Holmes the addict – Brett and Cumberbatch would have their moments playing the detective high as a kite and a host of pastiches would explore the same ground – Meyer created a version of Holmes who was definitely the same man but losing control of himself to the power of the drug.

This short-circuited some critics who didn’t remember such things from school-boy readings of Doyle and hazier memories of Rathbone (those films, by the way, were basically pastiches in the style of Seven-Per-Cent Solution as well). But it’s a stroke of genius from Meyer, shifting and representing a familiar character in an intriguing way that expands our understanding and sympathy for him. Holmes may obsessively play with his hands and have a greater wild-eyed energy to him. He may sit like a coiled spring of tension and lose his footing. But he can still dissect Freud’s entire life-story from a few visual cues in a smooth and fluid monologue and his passion for logic, justice – as well as his bond with the faithful Watson (here bought closer to Doyle’s concept of a decent, if uninspired, man) – remain undimmed.

It helps that the film features a fantastic performance from Nicol Williamson. Few actors were as prickly and difficult – so could there have been a better choice to play the challenging genius? Williamson’s Holmes is fierce in all things. Introduced as a wild-eyed junkie, raving in his rooms and haring after leads, his behaviour oscillates between drug-fuelled exuberance to petulant paranoia. But there are plenty of beats of sadness and shame: Holmes is always smart enough to know when he no longer masters himself. When the mystery plot begins (almost an hour into the film), Williamson’s does a masterful job of slowly reassembling many of the elements of the investigative Holmes we are familiar with – the focus, the energy, the self-rebuke at mistakes and the excitement and wit of a man who loves to show he’s smarter than anyone else.

The film is strongest as a character study, in particular of Holmes. Its most engaging sections take Holmes from a perfectly reconstructed Victorian London (including a loving, details-packed recreation of 221B from production designer Ken Adam) to waking from a cold turkey slumber full of apologies for his cruel words to Watson. Seeing Watson’s quiet distress at Holmes state, and the great efforts he takes to help him, are a moving tribute to the friendship at the book’s heart. The clever way Meyer scripts Holmes’ ‘investigation’ into Moriarty (an amusing cameo from Laurence Oliver, his mouth like a drooping basset hound) sees him apply all his methods (disguise, methodical reasoning, unrelenting work) in a way completely consistent with Doyle but clearly utterly unhinged.

That first half serves as a superb deconstruction of the arrogance of literature’s most famous detective, who won’t admit the slightest flaw in himself. It’s still painful to see a frantic Holmes, desperate for a hit, causing a disturbance in Freud’s home and denounce Watson as “an insufferable cripple” (a remark met with a swift KO and later forgiven). Holmes’ cold turkey sequence is a fascinating sequence of nightmareish hallucinations, as he is plagued by visions of cases past (The Engineer’s Thumb, Speckled Band and Hound of the Baskervilles among them) and the eventual awakening of Holmes as a contrite, humbled figure very affecting.

Bouncing off Williamson we have the traditional “Watson” role split between that character and Freud. Robert Duvall is a very unconventional choice as Watson – and his almost unbelievably plummy accent takes some getting used to – but he gives the character authority without (generously) giving him inspiration. Limping from a war wound (another touch of the novels often missed until now), he’s dependable, loyal and goes to huge lengths to protect his friends.

But most of the traditional role is actually given to Freud, played with quiet charm and authority by Alan Arkin. Intriguingly the film places Freud as a combination of both men’s characters. He has the analytical mind of Holmes, investigating the subconscious. But he also chases after errands for Holmes, “sees but does not observe” during the case in the manner of Watson and eventually becomes an active partner in confronting the villains.

The actual mystery (taking up less than 40 minutes of the film’s runtime) can’t quite maintain the momentum, being a rather trivial affair (greatly simplified from the book) revolving around a cameo from Vanessa Redgrave as a fellow drug addict Holmes feels a touching sympathy for. Jeremy Kemp makes a fine swaggering bully, but his greatest moment is actually his pre-mystery anti-Semitic confrontation with Freud at a sports club, culminating in a Flemingesque game of real tennis between the two. If the film has any moment that tips into outright comedy, it’s a closing train chase that involves Holmes, Watson and Freud dismantling the train carriage to burn the wood as fuel.

But the real heart of the film is Holmes. Throughout the film we are treated to brief visions of the boyhood Holmes slowly climbing a staircase. What he saw at the top of that staircase is buried deep in his subconscious, with the final act of the film revealing all under hypnosis. It’s an intriguing motivator for all Holmes has become, just as it is surprisingly shocking. As Watson comments, the bravest act is sometimes confronting ourselves: The Seven-Per-Cent Solution treats the detective with huge respect, while pushing him into psychological waters Doyle would never have dreamed of. It’s why the film (and Meyer’s book) is a fascinating must-see for Holmes fans: it takes the material deeper, but never once forgets its loyalty to the source material.