The mechanics of courtroom showmanship is ruthlessly exposed in this gripping drama

Director: Otto Preminger

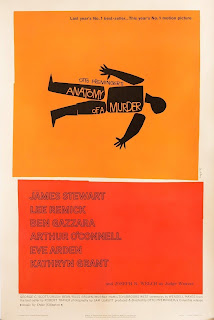

Cast: James Stewart (Paul Biegler), Lee Remick (Laura Mannion), Ben Gazzara (Lt Frederick Manion), Arthur O’Connell (Parnell McCarthy), Eve Arden (Maida Rutledge), Kathryn Grant (Mary Pilant), George C. Scott (Claude Dancer), Orson Bean (Dr Matthew Smith), Russ Brown (George Lemon), Murray Hamilton (Alphonse Paquette), Brooks West (Mitch Lodwick), Joseph N Welch (Judge Weaver)

Winston Churchill once said Democracy was the worst form of government, except for all the others. You could say something similar about trial by jury: it ain’t perfect, but it’s better than any other justice system we’ve given a spin to in human history. Trials aren’t always forums for discovering truths: they are stages to present arguments (or stories), and they are won by whoever has the best one. Maybe cold, hard facts and evidence make up your story, maybe perceptions. Maybe it’s about how you tell the story. Elements of all three are found in Otto Preminger’s brilliant courtroom drama, Anatomy of a Murder.

In a small town in Michigan, a US army lieutenant, Frederick Manion (Ben Gazzara) is arrested for the murder of innkeeper Barney Quill. Manion says he did the deed only because Quill raped Manion’s wife Laura (Lee Remick). Representing him is lawyer Paul Biegler (James Stewart), a former district attorney looking to start-up a new practise. On the opposite side is new DA Mitch Lodwick (Brooks West) and, far more of a worry, hot-shot lawyer Claude Dancer (George C. Scott) all the way from the Attorney General’s office. They say there was no rape – only a jealous murder after a consensual affair. It’s he-said-she-said, only “he” is dead. How will the trial clear that one up?

Otto Preminger was the son of a noted Austrian jurist, and Anatomy of a Murder can be seen as a tribute to his father, and to the process of the law itself. Not that it’s a hagiography. The film recognises the virtues as well as the faults of the system. Above all, that the system is not perfect, it can’t base every decision on firm facts and often requires people to take leaps of faith based on their gut instinct about who may, or may not, be telling the truth.

Preminger’s film does its very best to put us in the position the jury is in. We get no real evidence about what happened beyond what they get, and very few bits of additional information (except, perhaps, for seeing what many of the characters are like outside of the courtroom). Instead, the viewer is asked to make their mind-up on whether events fell-out as Manion claims (or not) based on our own judgement of the probabilities and of his (and Laura’s) character. The film opens with the crime committed and closes shortly after the verdict: there are no flashbacks or pre-murder scenes to help nudge us towards one view or another. The murder victim appears only as a photo. Like the jury we have to call it on what we see in front of us.

Anatomy of a Murder also makes clear there are plenty of shades of grey in the process of justice. During his first consultation with Manion, Biegler carefully suggests he consider whether he was in fact insane when he committed the deed – as that sort of defence will be much easier, since he doesn’t deny the killing. Sure enough, on their second meeting, Manion is now deeply unsure about his state of mind. Biegler then works backwards to establish precedent for the plea (a finds a single, over 75 years old one) to pull together a defence of irresistible impulse and to peddle hard a picture of the victim as an unrepentant rapist practically asking for a wronged husband to do the deed.

Biegler’s case is flimsy – but the key thing is to present it with pizzazz. And that’s what he’s got. Stewart’s performances in Hitchcock classics are highly regarded, but this might well be his finest dramatic performance. This is a brilliantly sly deconstruction of Stewart’s aw shucks charm: Biegler promotes an image of himself as a down-on-his-heels, bumpkin-like country lawyer, punching above his weight against the big city lawyers, Stewart dialling up the famous drawl. But it’s miles from the truth: Biegler is a former DA, an experienced trial lawyer and a formidable advocate. Stewart flicks the switch constantly, visibly putting on his persona like a skin, shedding it when no longer needed.

There is a constant suggestion that everything Biegler does is for effect. From fiddling with fishing tackle during the prosecution’s opening statements, to furious court-room theatricals as he thuds tables at slights and injustices. All of it is carefully prepared, rehearsed and delivered to make an impact on the jury. The constant parade of effect, manufactured outrage and appeals to an “us against them” mentality provokes exasperation from his opponents and a weary toleration from the Judge (played by real-life McCarthy confronting attorney Joseph N Welch). Stewart uses his Mr Smith Goes to Washington nobility, but punctures it at every point with Biegler’s cynicism and opportunism. Biegler, at best, persuades himself his client is innocent – but I would guess he doesn’t really care either way. He immediately perceives the personalities of his clients and then does his best to shield their less flattering qualities from the jury.

The one advantage we have over the jury is the additional insight we get into this strange couple, living a possibly unhappy, and certainly love-hate, marriage. Manion plays wronged fury in the court – but Gazzara gives him a lot of self-satisfied smarm and bland indifference to his crime in real life, meeting every event with a smirk that suggests he’s sure he can get away with anything. Equally good, Lee Remick’s Laura presents such a front of decency and pain in court, you’ll find it hard to balance that with the promiscuous, blousy woman we see outside of it, who provocatively flirts with intent with anything that moves. But it’s all about the show: present them right, and these unsympathetic people can be successfully shown as a conventional loving couple.

The prosecution is playing the same game. George C. Scott is superb as a coolly professional lawyer, who will use any number of tricks – from angry confrontation, to seductive reasonableness – to cajole a witness to say anything he wishes them to say. He will turn on a sixpence from being your friend, to berating you as a liar. And he’s not averse to his own morally questionable plays in court. Like Biegler, he knows presenting a good story is what is needed to win: the truth (or otherwise) isn’t enough.

Anatomy of a Murder still feels like a hugely insightful look at the legal process. Most of its runtime takes place in court, which Preminger shoots with a calmly controlled series of long-takes and two-shot set-ups, that help turn the film into something of a play (as well as a showpiece for fine acting). Along with its very daring (for the time) exploration of rape, it has a very cool soundtrack from Duke Ellington, that drips with allure and gives the film a lot of edge. The acting is all brilliant – along with those mentioned, Eve Arden is first-class as Biegler’s loyal secretary and Arthur O’Connell sweetly seedy as his heavy-drinking fellow lawyer. Anatomy of a Murder gives a first rate, at times cynical, look at the flaws and strengths of trial by jury – and is an outstanding courtroom drama.