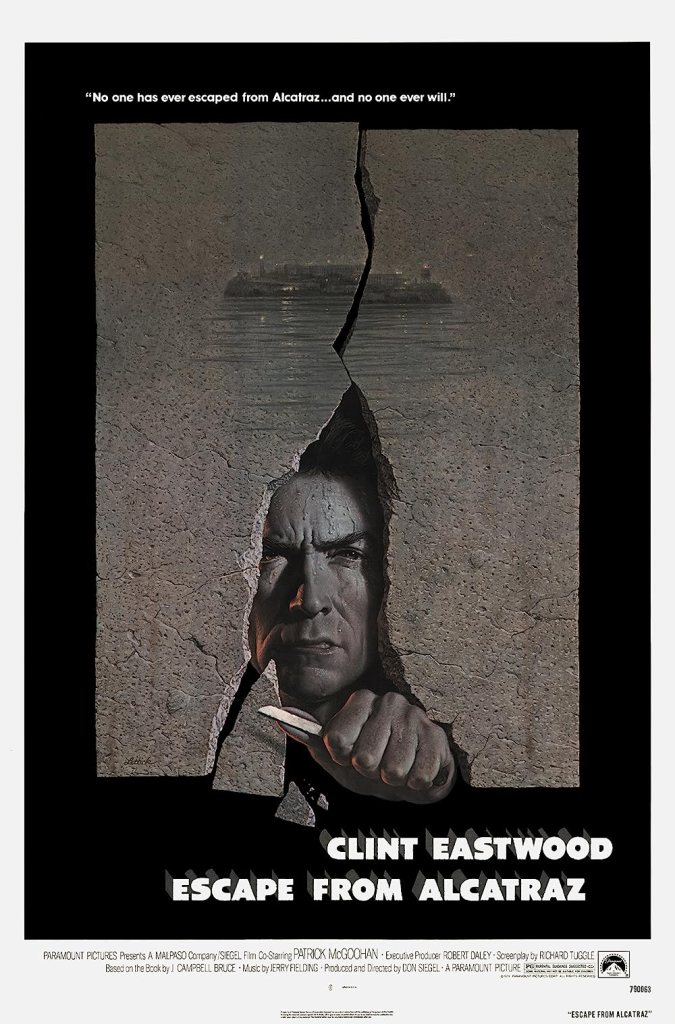

Siegel’s quietly observed prison break drama masters the small details

Director: Don Siegel

Cast: Clint Eastwood (Frank Morris), Patrick McGoohan (The Warden), Fred Ward (John Anglin), Jack Thibeau (Clarence Anglin), Larry Hankin (Charley Butts), Frank Ronzio (Litmus), Roberts Blossom (Chester “Doc” Dalton), Paul Benjamin (English), Bruce M Fischer (Wolf Grace)

In 1962, three men dug their way out of the cells in Alcatraz, climbed into a raft made of raincoats and sailed into San Francisco Bay and mystery. Not a trace was ever seen again of Frank Morris (Clint Eastwood), John Anglin (Fred Ward) or Clarence Anglin (Jack Thibeau), but their story became a cause celebre. Some say they disappeared to South America – many more believe they drowned in the freezing cold water of the Bay. Siegel’s film covers the details of the escape attempt – and leaves more than a hint that they escaped.

Escape from Alcatraz is a quintessential prison movie. It’s got the complete genre checklist: sadistic wardens, bullying in the courtyard, the threat of rape in the showers, solitary confinement, boring routines and jobs, unfair access to privileges, cagey alliances, the little details of a plan coming together, hair’s-breadth escapes from being caught and a “we go now or not at all” climax. It’s all mounted extremely well by Siegel, shot on location with such a searing coldness you can practically feel the chill the prisoners suffered all the time.

Alcatraz is made up of two things: quiet and time. Siegel’s film therefore delves into both of these things. From its opening montage detailing Morris’ arrival at the prison – on the boat, checking-in, cavity searches and tramping naked down to his cell – images and silence tell their own story. For the guards, words are formulaic and repetitive. Eastwood as Morris is barely ever out of shot but doesn’t speak for ten minutes. It’s the same for many other sequences, detailing prison life: quiet conversations in the yard, the pointless moves from place to place, the grinding procedure.

Time stretches without meaning in Alcatraz, so it’s no great sacrifice for Morris to work out that he can scratch away the brickwork around the drain in his cell and create a hole large enough to allow him to get to the unguarded ventilation corridors on the other side. (He works out it connects – eventually – to the outside by observing a cockroach crawl out of his cell.) Morris then reckons he’s got nothing better to do than to scratch away at that wall with a stolen nail pick, a labour that will take him months to extend the hole to something he can climb through.

Siegel also makes a great deal of this through his long-earned knowledge of how best to work with his star. This is one of Eastwood’s finest performances, a slate of determined, dry-witted stillness that communicates great thoughtfulness and ingenuity behind a stoic exterior. Morris maybe a compulsive thief, but he’s no fool – and he doesn’t suffer them either. He’s contemptuous of the self-importance of many of the warden and unrelenting in his determination to use whatever he can lay his hands on to help facilitate his escape attempt.

You’d be desperate to escape from Alcatraz too. Grim, very cold and crowded with bullies like Wolf (Bruce M Fischer), a puffed-up psychopath looking for a new punk (though as Quentin Tarantino said in a recent book, no one alive would look at Clint Eastwood and believe he’d be an easy shower victim). Meals are vile and the punishment of solitary is beyond tough: pitch black cells, only interrupted by the door being flung open so a high-pressure hose can ‘shower’ you with cold water (even Morris is reduced to something close to trembling wreck after a month of this treatment in the hole). It all leads into his determination to use anything he can to get out.

Siegel’s film loves the tiny details of small, inconsequential items converted into the means to escape. Unwanted magazines from the library become papier-mache to craft dummy heads to disguise the gang’s absence from their beds while they make preparations the other side of their wall. An accordion case smuggles goods around the prison. Makeshift candles are assembled. A set of portrait paints are used to paint the dummies and create a cardboard fake wall to place over the newly created hole. We see the painstaking effort to assemble enough coats to create their life-raft, the puzzling out of what is needed to get them from the ventilation roof to the other side.

Escape from Alcatraz presents these Herculean labours with simplicity but a patient eye for detail that makes them become strangely noble and hugely tense. You put aside your knowledge that these are hardened criminals – the film does everything it can to downplay their offences – and instead focus on them as victims of an unjust system, with “the man” crushing any hope from them.

As such, Patrick McGoohan has a huge amount of fun in a lip-smacking role as the prison warden. (It’s fun to see the world’s most famous Prisoner as the man handing out the numbers.) McGoohan’s unnamed warden has everything the men have not – not least words. He’s not starved by silence, but pontificates at pompous length about his theories of incarceration and the inevitable pointlessness of rehabilitation. Just to make sure our sympathy for the prisoners is complete, he’s also a vindictive bully, stripping prisoner “Doc” (Roberts Blossom) of his painting privileges because he doesn’t like a portrait made of him (tipping Doc into depressive self-harm), then provoking old-timer Litmus (Frank Ronzio) into a risky physical altercation. He’s unjust, unfair and mean.

So when he says at the end that he’s certain the prisoners died, of course we don’t want to believe him. Not least since we’ve been with the prisoners every minute of their desperate throw of the dice. In real life, they almost certainly froze to death in the Bay, their raft not being strong enough to help them complete the mile long swim before the icy water paralyzed them. But Escape from Alcatraz makes you want to believe they could have got away.