Excellent acting almost saves a neutered, inverted version of Williams’ powerhouse play

Director: Richard Brooks

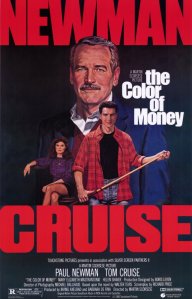

Cast: Elizabeth Taylor (Maggie Pollitt), Paul Newman (‘Brick’ Pollitt), Burl Ives (‘Big Daddy’ Pollitt), Jack Carson (‘Gooper’ Pollitt), Judith Anderson (‘Big Mama’ Pollitt), Madeleine Sherwood (Mae Flynn ‘Sister Woman’ Pollitt), Larry Gates (Dr Baugh), Vaughn Taylor (Deacon Davies)

There is a fun little anecdote of Tennessee Williams running into a crowd of people lined around the block to catch Cat on a Hot Tin Roof at their local multiplexes and loudly begging them “Go home! This movie will set the industry back 50 years!” You can sort of see why Williams was a bit pissed. It’s a miracle really that Cat on a Hot Tin Roof works at all. The studio snapped up this Broadway mega-hit and promptly instructed Richard Brooks to remove all the content that worked with a bunch of New York Times readers, but wasn’t going to fly in a mid-West fleapit. What we end up with is a curious, mis-aligned, neutered work that arguably inverts several of Williams’ points and is reliant on its incredibly strong, charismatic acting to work.

Brick (Paul Newman) is a former College sports star, now adrift in life, trapped in an unhappy marriage with Maggie (Elizabeth Taylor) who he resents and blames for the suicide of close friend Skipper. All Maggie’s attempts to rediscover any love is met with cold, blank disinterest as Brick hits the bottle big-time. Maggie keeps up the front of wedding bliss, as she is determined they will win their share of the inheritance from Brick’s father ‘Big Daddy’ (Burl Ives) who believes he’s merely under-the-weather, but is in fact dying. This news is also being kept from his devoted (but privately barely tolerated by Big Daddy) wife Big Mama (Judith Anderson), while Brick’s brother’s Gooper (Jack Carson) and his wife Mae Flynn (Madeline Sherwood) makes aggressive pitchs to cement Big Daddy’s fortune for themselves.

This simmering Broadway adaptation of a Southern family weighted down by lies (or mendacity as they love to call it), concealments and barely disguised resentments, was a smash hit but a very mixed film. It’s weighed down by both too much respect of the theatrical nature of the play, and too little interest in its actual message. Richard Brooks’ production largely restricts itself to interspersing wider shots with some reaction shots and sticks very much to its ‘same location for each act’ set-up. It’s a surprisingly conservative and safe re-staging of a hit play.

Despite Brooks’ liberal re-writing of the dialogue (of which more later), it remains a very theatrical rather than cinematic piece, largely devoid of imaginative editing or photography. The attempts to ‘open up’ the piece introduced by Brooks feel pointless or add very little (such as witnessing the accident where Brick breaks his leg or travelling to the airport to see the arrival of Big Daddy’s plane). Compared to the inventive and dynamic use of single-location shooting in Lumet’s 12 Angry Men, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof feels considerably more stately and reserved, and is far less successful in using the tricks of cinema to successfully build tension and conflict.

What it shares however with 12 Angry Men is the electric acting. Elizabeth Taylor gives one of her finest performances, her Maggie bubbling with sexual and emotional frustration, reduced to hurling physical and verbal punches at Brick in an attempt to get any sort of emotional rise out of him. She makes Maggie, for all her desperation and confusion, surprisingly sympathetic. Taylor manages to be both selfish and domineering while also showing how broken up Maggie is with shame and guilt. It’s a detailed, intense, passionate performance.

It also works perfectly opposite Paul Newman’s brooding intensity as Brick. This is the handsome, blue-eyed legend inverting his charisma into something insular, at times merely starring in self-loathing into the middle distance as other speak at him, only rarely rising to let rip at others with contempt and fury. Newman is a force of quiet, emotional anger, even if (stripped of his character’s primary motivation) he comes across at times like a spoilt child who never really grew up rather than the tortured man trapped in a lie of a life, that Williams intended (Brooks even frames him at one point with a high-school football of himself behind him, his past literally haunting him).

Burl Ives would certainly have won an Oscar for this, if he hadn’t won that year for The Big Country. Recreating his Tony Award winning role, he’s a whirligig force of nature as Big Daddy, bullishly insistent on getting his own way, shrugging off with irritation his wife’s affection (an effectively unsettled Judith Anderson) and hiding his own fear at oncoming death in a relentless pursuit of the future. Ives also nails Big Daddy’s outstanding late speeches, investing them with a deep sense of melancholy and sadness under the bombast and strength. It’s a great performance. Jack Carson is perfectly, anonymously uninteresting as ‘other son’ Gooper and Madeline Sherwood hits the beats of shrill hostility she’s asked for as his wife Mae Flynn.

That these performances work so well is a tribute to the underlying strength of a play that has been radically, almost disastrously, lobotomised by Brooks into something that flattens, blurs and (at points) radically inverts the intention. Putting it bluntly, Williams’ original used Brick’s unspoken (perhaps even subconscious) homosexual attraction to Skipper as the root cause of his disastrous marriage and booze-laden depression. Maggie, all too-aware of her husband’s sexual orientation, fumes in frustration at his lack of interest in making the inheritance-required babies. Even Big Daddy suspects this massive unspoken secret at the heart of a family. The fact this remains unspoken to the end, that the characters carry on with the fake fiction of the Pollitt dynasty is a damning indictment of the hypocrisy of American family life.

That wasn’t going to wash in Hollywood. No hint of Brick’s homosexuality could be allowed: in fact, Newman’s heteronormative virility is repeatedly stressed (at one point he even embraces Maggie’s dressing gown in romantic longing). It weakens both characters – for all the skill of Newman and Taylor, it makes both characters shallower, two people letting sulks and pride stand between happiness, rather than two people trapped into a doomed cycle. The film resolutely associates happiness with love and duty to the family unit, emphatically not what Williams’ play suggested.

No wonder he was pissed. A daring play about Southern family hypocrisy and buried secrets, where the burden of the family is a deadweight crushing people is turned into a straight (in every sense) celebration of it. It makes the play a conservative, reassuring lie, as much as a mendacity as the characters talk about. So maybe Williams was right to berate that crowd. Still it pissed Brooks off mightily: he pithily retorted it was a bit rich of Williams to kick up such fuss over a film which made him very wealthy. I guess at least there Brooks makes a strong point.