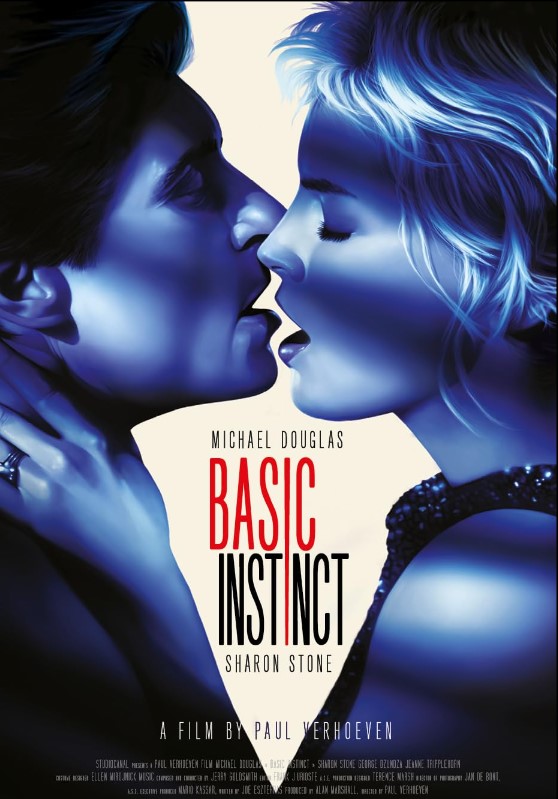

A sensationalist hit, this Trashy Hitchcock-pastiches looks very pleased with its own naughtiness today

Director: Paul Verhoeven

Cast: Michael Douglas (Detective Nick Curran), Sharon Stone (Catherine Tramell), George Dzundza (Detective Gus Moran), Jeanne Tripplehorn (Dr Beth Garner), Dorothy Malone (Hazel Dobkins), Denis Arndt (Lt Philip Walker), Leilani Sarelle (Roxy Hardy), Bruce A Young (Detective Sam Andrews), Chelcie Ross (Captain Talcott), Wayne Knight (Assistant DA John Correli), Stephen Tobolowsky (Dr Lamott)

If there is one thing Basic Instinct proves for sure, it’s that Paul Verhoeven is a very naughty boy. A sensational smash hit in 1992, largely because of the instant iconic status of that scene (you know which one), Basic Instinct remixes Hitchcock (especially Vertigo and Psycho) with lashings of explicit sex and violence, a touch of The Silence of the Lambs and a dollop of Fatal Attraction. It’s a deeply silly, dirty film that was a sort of Fifty Shades of its day: vanilla porn for those who feel too self-conscious to actually go and watch a real one.

Catherine Trammell (Sharon Stone) is number one suspect for the murder of her boyfriend (or rather as she describes him “the guy I was fucking”) for two reasons: one she published a novel a few weeks earlier where she explicitly described the crime in detail and two she’s an obvious Hannibal Lector-ish genius psychopath. Doesn’t stop weak-willed detective Nick Curran (Michael Douglas) from becoming obsessed with her, sucked into a wild sexual affair. But is Catherine a misunderstood unlucky victim, or the genius manipulator her old college rival Dr Beth Garner (Jeanne Tripplehorn) – also Nick’s on-and-off girlfriend and psychiatrist – says she is?

Basic Instinct was the most expensive script ever sold, earning Joe Eszterhas $3million for what he claimed was fourteen days’ work. And you can see why – it’s got everything audiences could need for an addictive, trashy bit of fun. A femme fatale who is also a genius psychopath! A handsome macho cop! Brutal murders! A puzzle interesting enough to keep ticking over but obvious enough that you don’t need to think about it too much! And of course, lots and lots and lots of sex! And then even more sex! No wonder people saw dollar bills – at the very worst they had a chance at a so-bad-its-good box office smash.

But the good stuff. Basic Instinct’s comic-book Hitchcock pastiche actually works rather well, helped enormously by a marvellous Oscar-nominated score by Jerry Goldsmith, which brilliantly channels Bernard Herrmann’s luscious Vertigo strings. It’s no exaggeration to say Goldsmith’s score dramatically improves the film, from adding tension to a drawn-out elevator trip to adding a film noir lyricism to Catherine and Nick’s rather forced sexualised banter. Verhoeven also really knows his business: the film’s famous interrogation scene works as well as it does through his skilful editing between wide angles, close-ups and POV shots, aided by the striking uplighting from cinematographer Jan de Bont.

That scene – and the film – also works because of Sharon Stone. Taking on a role turned down by almost every single woman in Hollywood, Stone seizes hold of a part she knew was a once in a lifetime opportunity. Nick may be the lead – and Douglas, in the middle of his run of weak modern American men bewitched by strong women, may have been the high-paid star ($14 million to Stone’s $550k) – but both knew this was Catherine’s movie. Stone plays the role with a playful, sensual confidence and arrogant defiance, knowing full well she can seduce anyone. Despite the clunky dialogue, she makes Catherine sexy, smart and just about vulnerable enough to make some viewers doubt whether she’s the killer or not. (I mean she blatantly is, the film doesn’t really try and pretend otherwise. Most of the fun is seeing how shamelessly she can parade it and still get away with it.)

Away from that though, Basic Instinct is a terribly silly film, a well-made pandering to our lowest desires. Opening with an extremely graphic post-coitus stabbing frenzy (with blood spray everywhere and a nose skewered by an ice pick) – it then teases us three times that it will repeat this again after nearly every explosive session of rumpy-pumpy. Ah yes, the rumpy-pumpy. Basic Instinct slows at the half-way mark for an almost five-minute extended multi-angled, orgasm packed bit of horizontal jogging that Nick then rather pathetically spends most of the rest film bragging about being “the fuck of the century”.

But then Nick is a pathetic figure. Somehow keeping hold of his badge, despite gunning down two tourists while high on cocaine, he’s got such an addictive personality he makes Lloyd Bridges’ (“I picked the wrong week to quit sniffing glue!”) air traffic controller in Airplane look like a model of restraint. After internal affairs-mandated therapy (how’s that for a slap on the wrist) – hilariously compromised by Jeanne Tripplehorn’s Dr Garner crossing all ethical lines by repeatedly shagging him – Nick has proudly quit drugs, drink, smoking, and shooting before asking questions. Needless to say, under Catherine’s influence, he embraces all of these again, all while still managing to be the sort of middle-aged loser who wears a pullover to nightclub.

Eszterhas’ script mixes awful “tough” dialogue (“Looks like he got off before he got offed” Nick’s partner jokes over a victim) with clumsy psychological insight (my favourite is Tobolowsky’s consultant who confidently states two options: Trammel either did or didn’t do it – inevitably this childishly empty insight is met with the manly ‘tecs muttering “In English Doc!”) and blunt statements of the obvious (“She’s brilliant! And Evil!” screams poor Tripplehorn). The flirty banter is largely sold by Sharon Stone’s confidence, since the lines (“I’m not wearing underwear”) are hardly Double Indemnity. The film’s mystery is so irrelevant to its appeal (and, in many ways, plot), it merrily gets bogged down in several off-screen murders of characters we’ve never met.

Today Basic Instinct feels like a bizarre museum piece. George Dzundza’s sidekick cop is intended as comic-relief but comes across like a little ball of toxic masculinity. An early sex scene between Nick and Beth is pretty much impossible to watch today without thinking “yeah that’s rape”. The film uses bisexuality (though we only, of course, get girl-on-girl – Douglas made it clear he ain’t gonna kiss no man) as raw titillation, an entre for the soft porn of Douglas and Stone noisily going at it for about 10% of the film’s run time. Even the famous scene is uncomfortable to watch, since Stone has since made it clear she didn’t consent to that shot.

Basic Instinct is a deeply silly piece of trash. But then that was its appeal back then – no one felt they were actually watching Hitchcock when they sat down to this rip-off of the master (in fact Basic Instinct makes you feel it’s probably a relief the production code meant Hitchcock couldn’t give into his Verhoevenish instincts). Today most like to think of it as a sort of well played card trick. However, it’s hard not to feel a bit for Sharon Stone to whom it became a millstone (which she eventually exploited for a terrible belated sequel for which she pocketed $13.5million), despite being the person possibly most responsible for its success. So maybe Nick won in the end after all.