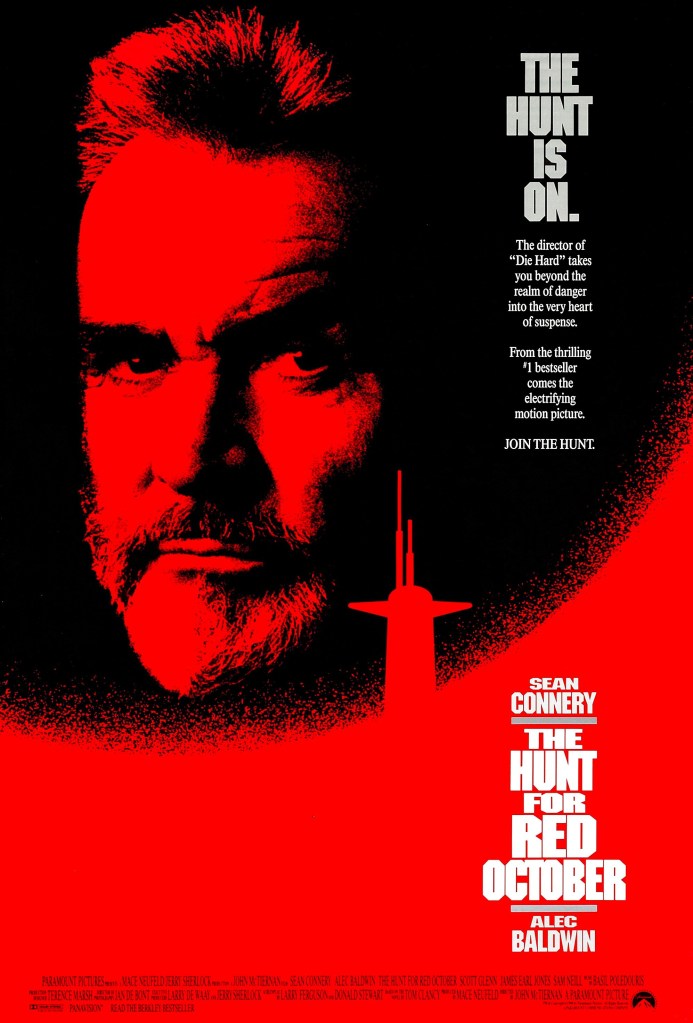

Shailing into Hishtory! The Hunt for Red October is the finest Tom Clancy adaptation made

Director: John McTiernan

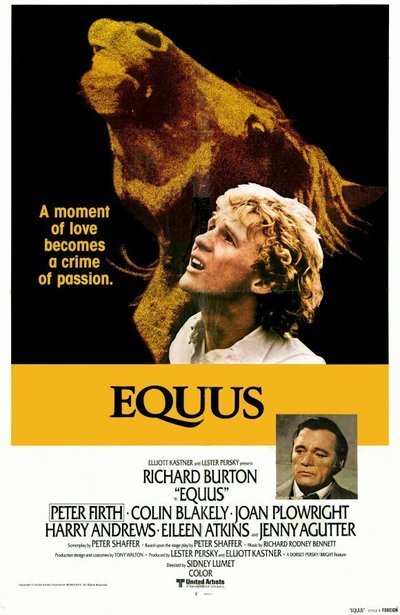

Cast: Sean Connery (Captain Marko Ramius), Alec Baldwin (Jack Ryan), Joss Ackland (Ambassador Andrei Lysenko), Tim Curry (Dr Petrov), Peter Firth (Ivan Putin), Scott Glenn (Commander Burt Mancuso), James Earl Jones (Admiral James Greer), Jeffrey Jones (Skip Tyler), Richard Jordan (National Security Advisor Jeffrey Pelt), Sam Neill (Captain Vasily Borodin), Stellan Skarsgård (Captain Viktor Tupolev), Fred Dalton Thompson (Rear Admiral Joshua Painter), Courtenay B Vance (PO Jones)

“We shail into Hishtory!” It’s the film that launched a thousand Sean Connery impressions. Only Connery could get away with playing a Soviet submarine captain with the thickest Scottish accent this side of Lithuania. He only took the role – from Klaus Maria Brandauer – at short notice, but he’s a pivotal part of the film’s success. The Hunt for Red October is a superb film, the finest Tom Clancy adaptation ever made and one of the cornerstones of the submarine genre. It expertly mixes beats of conspiracy, espionage, naval adventure and even touches of comedy, into a superbly entertaining cocktail.

Connery is Captain Marko Ramius, the USSR’s finest naval captain, given command of The Red October on its maiden voyage. The Red October is equipped with a technical miracle: a “caterpillar drive” that uses a water powered engine to run silently, making it invisible to sonar. So why is the entire Russian fleet being scrambled to find and sink the submarine? Could it be, as the USSR tells the US, that Ramius has gone mad and plans a nuclear strike? Or is it, as CIA analyst Jack Ryan (Alec Baldwin) argues, because Ramius plans to defect and bring the technological marvel with him?

Of course, we know Connery plans to defect. After all, we’ve already seen him murder shifty political officer Ivan Putin (Peter Firth – to whom alphabetical billing is very kind) and tell his handpicked crew of officers, led by loyal second-in-command Borodin (Sam Neill, so dedicated to affecting a Russian accent it’s as if he felt he needed to do in on behalf of himself and Connery) that there is no turning back. The film’s expert tension – and it rachets it up with all the precision of a well-oiled machine – is working out how. How will Ramius evade the Russian fleet? How will he manage to arrange his defection without communicating with the US? And will he and Ryan – unknowingly working together – persuade the US not to blow The Red October out of the water?

With McTiernan, in his prime, at the helm it’s not a surprise the film is expertly assembled. The parallel plot lines are beautifully intercut. Our two heroes, Ramius and Ryan, face very different obstacles (dodging Soviet torpedoes vs patiently making his case to sceptical superiors mixed with risky long-range travels to far-flung US subs) but somehow seem to be building a bond before they even meet. Ryan is an expert on Ramius and his career, while his thoughtful, good-natured decency is exactly the sort of American Ramius tells his crew they need to meet (as opposed to “some sort of buckaroo” – a word Connery relishes).

McTiernan isn’t just an expert mechanic though. There are lovely touches of invention and magic here. The Hunt for Red October has possibly one of the finest transitions ever. Connery, Neill et al start the film speaking in Russian. Ramius meets with Firth’s Putin (great name) in his quarters to open their orders. The two chat briefly in Russian, then Putin reads from Ramius’ copy of the Book of Revelations. As Firth reads (in fluent, expertly accented Russian), McTiernan slowly zooms in on his lips until he reaches the word “Armageddon” (the same in both languages) – the camera then zooms out and both Firth and Connery continue the scene in English (Firth switching mid-shot from Russian to English without missing a beat). It’s a beautifully done transition, rightly a stand-out moment.

But then it’s a film full of them. Many rely on Connery’s performance, superb as Ramius (this was his career purple patch, where one effortlessly excellent performance followed another). Ramius has a grizzled sea-dog charm and a twinkle in his eye, but he’s also nursing a private grief and pain that motivates his defection. He can be demanding of his men, but also inspires loyalty – that “We Shail into Hishtory!” pep-talk speech is delivered perfectly (and McTiernan makes Soviet sailors singing the Soviet anthem a punch-the-air moment even though (a) we know they are technically the bad guys and (b) we know Ramius is lying through his teeth in his speech). But he is always a commander, Connery investing him with every inch of his movie star cool.

Ramius is also an interesting reflection, in a way, of Ryan. Played with a great deal of young-boy charm by Baldwin (and also wit, Baldwin dropping impersonations of other cast members into the film – including a stand-out Connery), Ryan is brave, determined but also slightly naïve and out-of-his-depth. But like Ramius he respects his “enemy”, is open to negotiation, thinks before he acts and wants to save lives. The two even share similar upbringings. The film triumphantly shows a desk man, spreading his wings and doing stuff he couldn’t imagine: the guy who tells an air hostess in an early scene he can’t sleep on flights due to fear of turbulence, will later have himself dropped into the sea from a perilous helicopter flight, steer a Russian sub and duke it out with the last Soviet hard-liner standing in The Red October’s missile room.

McTiernan shoots Ryan’s conversations like combat scenes: quick reversals and cross shots and even whip pans and zooms. It ratchets up the tension and drama in these sequences – and allows him to play it cooler in the sub shots which (with its more constrained set) where patient studies of tense faces follow sonar reports of the approach of torpedoes or enemy subs. Sound is a triumph in Red October – every ping or sonar shadow is sound edited to perfection, with much of its tension coming from their perfect rising intensity.

It builds towards a superb resolution as several plot threads come together in a dramatic face-off that gives us everything from sub v sub to gunfights, with tragedy and triumph all mixed in. It’s a perfect ending to a film that is a masterpiece of plotting and construction, acted to perfection by the whole cast (Connery and Baldwin, but also Jones, Neill, Glenn – perfect casting as a no-nonsense naval captain – and several reliable players in smaller roles). McTiernan directs with exceptional pace and excitement, it’s sharply scripted and technically without a fault – from its gleaming Soviet sub (with church like missile room) to brilliantly edited sound-design. It’s a joy every time I watch it.