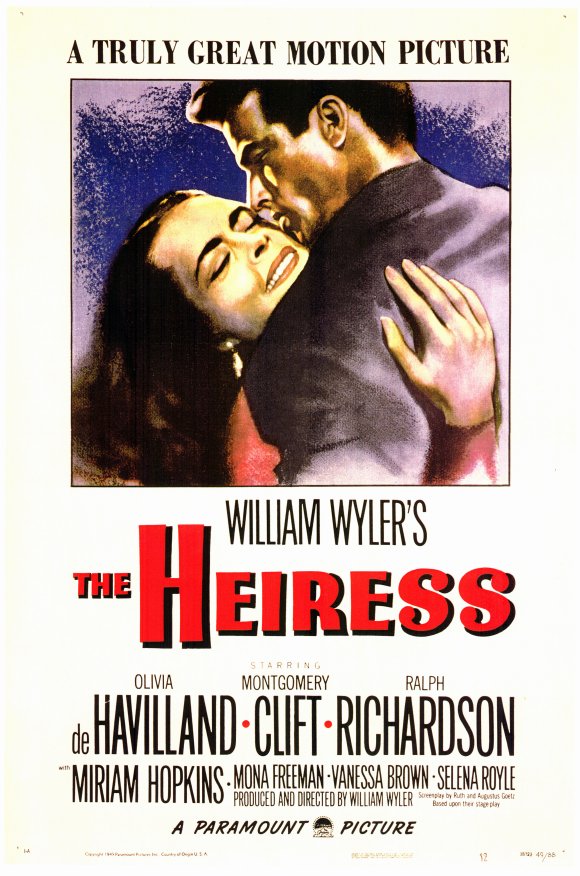

Is it love or is it avarice? Wyler’s sumptuous costume drama is a brilliant translation of Henry James to the screen

Director: William Wyler

Cast: Olivia de Havilland (Catherine Sloper), Montgomery Clift (Morris Townsend), Ralph Richardson (Dr Austin Sloper), Miriam Hopkins (Lavinia Penniman), Vanessa Brown (Maria), Betty Linley (Mrs Montgomery), Ray Collins (Jefferson Almond), Mona Freeman (Marian Almond), Selena Royle (Elizabeth Almond), Paul Lees (Arthur Townsend)

Pity poor Catherine Sloper (Olivia de Havilland). She’s seems destined forever to be the spinster, the last person anyone glances at during a party. Her father Dr Sloper (Ralph Richardson) can’t so much as walk into a room without gently telling how infinitely inferior she is to her mother. And when a man finally seems keen to court her, her father tells her that of course handsome Morris Townsend (Montgomery Clift) will only be interested in her inheritance. After all, there is nothing a young man could love in a forgettable, dull, second-rate woman like Catherine. He’s cruel, but is he right – is Morris a mercenary?

The Heiress was adapted from a play itself a version of Henry James’ Washington Square. It’s bought magnificently to the screen in a lush, sensational costume drama that comes closer than anyone else at capturing those uniquely Jamesian qualities of ambiguity and contradictory motives among the New American elites. Magnificently directed by William Wyler, it brilliantly turns a theatrical character piece into something that feels intensely cinematic, without once resorting to clumsy ‘opening up the play’ techniques. And it marshals brilliant performances at its heart.

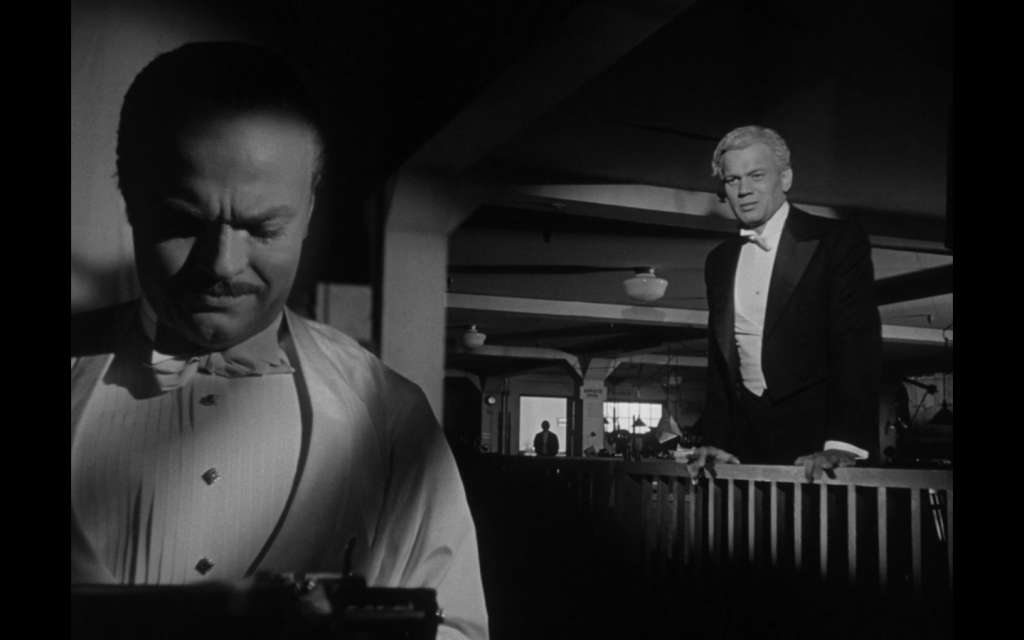

Sumptuously costumed by Edith Head, whose costumes subtly change and develop along with its central character’s emotional state throughout the story, it’s largely set in a magnificently detailed Upper New York household, shot in deep focus perfection by Leo Tover, which soaks up both the reaction of every character and the rich, detailed perfection of decoration which may just be motivating some of the characters. Not that we can be sure about that, since the motives of Morris Townsend and his pursuit of Catherine remain cunningly unreadable: just as you convince yourself he’s genuine, he’ll show a flash of avarice – then he’ll seem so genuinely warm and loving, you’ll be sure he must be telling the truth or be the world’s greatest liar.

Catherine certainly wants it to be true – and believes it with a passion. The project was also a passion piece for de Havilland, and this is an extraordinary, Oscar-winning performance that delves deeply into the psyche of someone who has been (inadvertently perhaps) humiliated and belittled all her life and eventually reacts in ways you could not predict. Catherine is clumsy, naïve and lacking in any finesse. With her light, breathless voice and inability to find the right words, she’s a doormat for anyone. She even offers to carry the fishmonger’s wares into the house for him. At social functions, her empty dance card is studiously checked and her only skill seems to be cross-stitch.

She is an eternal disappointment to her father, who meets her every action and utterance with a weary smile and a throwaway, unthinking comment that cuts her to the quick. Richardson, funnelling his eccentric energy into tight control and casual cruelty, is magnificent here. In some ways he might be one of the biggest monsters in the movies. This is a man who has grown so accustomed to weighing his daughter against his deceased wife (and finding her wanting) that the implications of the impact of this on his daughter never crosses his mind.

Catherine is never allowed to forget that she is a dumpy dullard and a complete inadequate compared to the perfection of her mother. Richardson’s eyes glaze over with undying devotion when remembering this perfection of a woman, and mementoes of her around the house or places she visited (even a Parisian café table later in the film) are treated as Holy Relics. In case we are in any doubts, his words when she tries on a dress for a cousin’s engagement party sum it up. It’s red, her mother’s colour, and looks rather good on her although he sighs “your mother was fair: she dominated the colour”. Like Rebecca this paragon can never be lived up to.

So, it’s a life-changing event when handsome Morris Townsend enters her life. There was criticism at the time that Clift may have been too nice and too handsome to play a (possible) scoundrel. Quite the opposite: Clift’s earnestness, handsomeness and charm are perfect for the role, while his relaxed modernism as an actor translates neatly in this period setting into what could-be arrogant self-entitlement. Nevertheless, his attention and flirtation with Catherine at a party is a blast from the blue for this woman, caught mumbling her words, dropping her bag and fiddling nervously with her dance card (pretending its fuller than of course it is).

Her father, who sees no value in her, assumes it is not his tedious child Morris has his eyes on, but the $30k a year she stands to inherit. And maybe he knows because these two men have tastes in common, Morris even commenting “we like the same things” while starring round a house he all too clearly can imagine himself living in – by implication, they also have dislikes in common. (And who does Sloper dislike more, in a way, than Catherine?) Morris protests his affections so vehemently (and Sloper lays out his case with such matter-of-fact bluntness) that we want to believe him, even while we think someone who makes himself so at home in Sloper’s absence (helping himself to brandy and cigars) can’t be as genuine as he wants us to think.

As does Catherine. Part of the brilliance of de Havilland’s performance is how her performance physically alters and her mentality changes as events buffet her. A woman who starts the film mousey and barely able to look at herself in the mirror, ends it firm-backed and cold-eyed, her voice changing from a light, embarrassed breathlessness into something hard, deep and sharp. De Havilland in fact swallows Richardson’s characteristics, Sloper’s precision and inflexibility becoming her core characteristics. The wide-eyed woman at the ball is a memory by the film’s conclusion, Catherine becoming tough but making her own choices. As she says to her father, she has lived all her life with a man who doesn’t love her. If she spends the rest of it with another, at least that will be her choice.

Wyler assembles this superbly, with careful camera placement helping to draw out some gorgeous performances from the three leads – not to forgetting Miriam Hopkins as a spinster aunt, who seems as infatuated with Morris as Catherine is. The film is shaped, at key moments, around the house’s dominant staircase. Catherine runs up it in glee at the film’s start with her new dress, later sits on it watching eagerly as Morris asks (disastrously) for her hand. Later again, she will trudge up it in defeated misery and will end the film ascending it with unreadable certainty.

The Heiress is a magnificent family drama, faultlessly acted by the cast under pitch-perfect direction, that captures something subtly unreadable. We can believe that motives change, grow and even alter over time – and maybe that someone can love somebody and their money at the same time (perhaps). But we also understand the trauma of constant emotional pain and the hardening a lifetime of disappointment can have. It’s the best James adaption you’ll ever see.