An uninspired prestige drama suddenly turns at the end into an intriguingly subversive drama

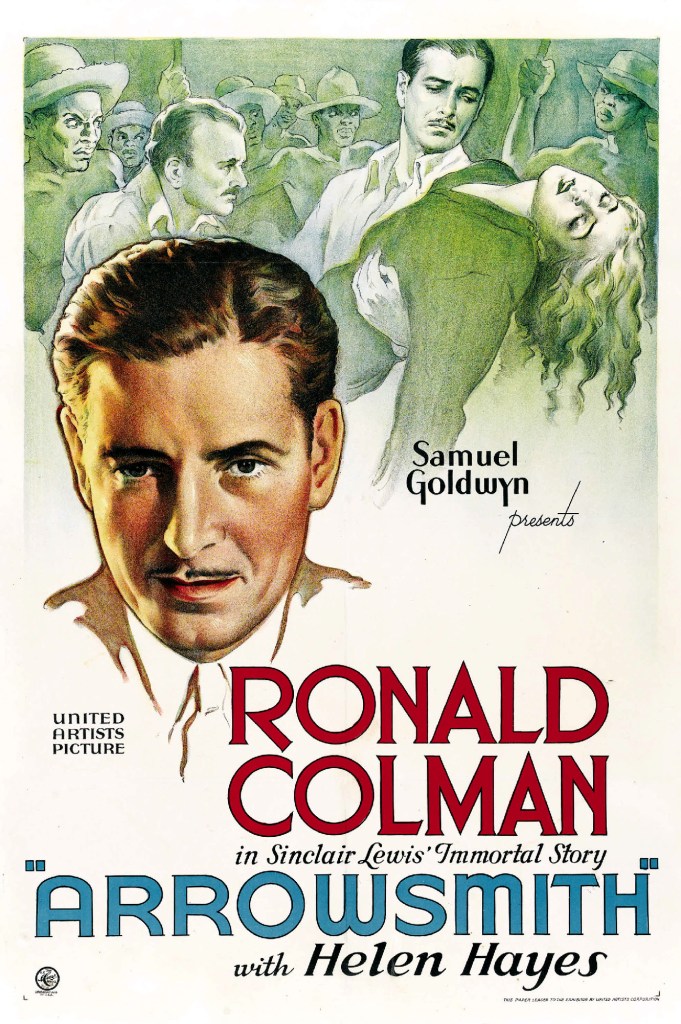

Director: John Ford

Cast: Ronald Colman (Dr Martin Arrowsmith), Helen Hayes (Leora Arrowsmith), Richard Bennett (Gustav Sondelius), A.E. Anson (Professor Max Gottlieb), Clarence Brooks (Dr Oliver Marchand), Alec B Francis (Twyford), Claude King (Dr Tubbs), Bert Roach (Bert Tozer), Myrna Loy (Mrs Joyce Lanyon), Russell Hopton (Terry Wickett), Lumsden Hare (Sir Robert Fairland)

A neat trivia question: what was the first John Ford film nominated for Best Picture? Not many people remember Arrowsmith today – although, since Ford was ordered by producer Samuel Goldwyn to not touch a drop of the sauce while making it, we can be pretty sure he did. Adapted from a hulking Pulitzer-prize winning novel by Sinclair Lewis, it was the epitome of prestige Hollywood filmmaking. It’s a far from a perfect film, but it contains flashes of real beauty and genius – and presents one of the most surprising, subversive visions of infidelity you’ll see in 30’s Hollywood.

Martin Arrowsmith (Ronald Colman) is desperate to be a high-flyer. A scientist and doctor, he’s wants to make his mark – and his mentors such as noted bacteriologist Professor Gottlieb (A.E. Anson) and Swedish scientist Gustav Sondelius (Richard Bennett) think he can. But Arrowsmith postpones his dreams for a spontaneous marriage to Leora (Helen Hayes), before re-embracing science. When plague breaks out in the West Indies, the Arrowsmiths travel there, ordered to test a possible cure on the natives: half will receive the cure, the other a placebo. But temptation and tragedy will be Arrowsmith’s constant companion there.

Arrowsmith is very much a film of two halves (or, in terms of its run-time, two-thirds, one-third). To be honest, much of its first hour is frequently rushed, ponderous and dull, flatly filmed with the air of uninspiring prestige production. Watching it play, it’s hard to connect a film as flat, perfunctory and serviceable as this with Ford’s energy and flair. It’s not helped by the accelerated storytelling. Stuffing in as much of Lewis’s door-stop best-seller as it can (the first fifteen minutes cover as many events as whole movies often content themselves with), the plot barrels along so fast it can leave your head spinning. Scenes either feel like sketches from a larger whole or like narrative cul-de-sacs included to tick a box from the novel.

Arrowsmith feels like a compromised film. I suspect Goldwyn’s aim was to cover the book. But I feel Ford’s interest – if he had one in the film’s opening hour – was the Arrowsmith marriage. On the surface this is your standard loving-husband-supportive-wife pairing. But, underneath, there is a lot more going on here. Everything about their courtship and registry office marriage feels perfunctory. Arrowsmith treats his wife with a fondness that never tips into passion. When she suffers a miscarriage (which prevents her having children), he is sad but moves on remarkably quickly. At one point, Leona discusses the idea of leaving her preoccupied, distant husband who disappears for days on end (you feel she’s only half joking). Arrowsmith calls her ‘old girl’, which feels rather complacent and smug.

You suspect Ford might be hinting that, frankly, Arrowsmith is a self-important shit with grandiose ideas. It’s an idea the film can’t quite push – Ronald Colman’s undoubted charm smooths off Arrowsmith’s rough edges, even while he makes him self-righteous and pompous. But as Leona (Hayes is excellent in subtly suggesting this woman is much more lonely than she admits) watches her house jerry-rigged into a Frankenstein-laboratory (his atrociously poor safety measures will come back to haunt him later) or is left for days alone at home, it’s hard not to feel this is a more complex, strained relationship than the film can openly say.

These half-stated implications lead us into the film’s final act in the West Indies, which almost redeems the slightly confused mish-mash it proceeds. From the opening shot of this sequence – focused on Clarence Brooks’ doctor (notable for treating a Black character as an assured professional) with his patients sitting on a balcony, excluded from the conversation about their health going on down below – it’s impossible not to see Ford’s sympathy more openly lying with the West Indian villagers, whose health is of little interest to the white population and who even our nominal hero (reluctantly) uses as guinea pigs for his cure. This powers us through a half-hour sequence that is by far-and-away the most focused and interesting of the entire film.

This tragedy-laden sequence not only buzzes with an indignation of the unfairness of this system – in which our hero is a semi-reluctant participant – but unleashes the most beautiful, shadow-filled, expressionistic lighting in the film. Ford signposts moments of high emotion by casting people’s bodies in shadow. This mesmerising effect is used brilliantly, combined with shots deliberately echoing each other (most strikingly two contrasting shots of the Arrowsmith home, both framed at low angles with foreground chairs – the second laced with tragedy). Visual imagery reflects, not least the cutting between two cigarettes smoked by the Arrowsmith’s. There is a host of heart-rendering, inventive ideas in visual storytelling: at one point, Arrowsmith’s phone call with a sweating colleague goes dead – we cut to see a shot of the empty phone on the other end bathed in shadow, enough to tell us his interlocutor has literally died mid-call.

This shadow-filled sequence also powers the film’s most subtle moment: possibly the most under-the-wire depiction of infidelity seen in the movies. The original novel made clear Arrowsmith was serially unfaithful. Here, he meets Myrna Loy’s wealthy heiress, to whom he admits an immediate kinship. At night, wordlessly, Ford cuts back and forth between Loy preparing for bed and Colman sitting (bathed in shadow) smoking and possibly waiting. Wordlessly the cuts go back and forth – and then fades to black as we see a shadow approach the door of Colman’s bedroom. You can miss it entirely: but its clear they sleep together. (A late scene with Colman and Loy, with a lingering handhold, feels like proof positive). A late scene of Colman filled with manic energy, in this context feels powered more by guilt and shame.

It’s subtle because we know that in scenes of open emotion and dramatic import we’ve seen faces thrown into shadow. When its repeated here, in an otherwise inconsequential scene, we’re having visually communicated to us something the film can’t openly tell us: Arrowsmith is cheating on his wife. It’s the highlight of a compelling final act, full of drama, tragedy and beautiful filmmaking. When the film leaves the West Indies for its lab-set coda, it returns to flat film-making and sudden, jarring plot developments. But for this half-hour section, it’s a fascinating, oblique, challenging and rewarding film: one of the best short films buried in a large one you’ll see. Arrowsmith may not be a classic, but’s it’s a fascinating film.