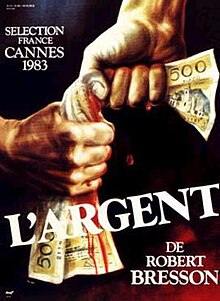

Bresson’s final film: challenging, cold, hard to watch, definitely leaves you thinking

Director: Robert Bresson

Cast: Christian Patey (Yvon Targe), Vincent Ricterucci (Lucien), Caroline Lang (Elise), Sylvie van den Elsen (Grey haired woman), Michel Briguet (Grey haired woman’s father), Beatrice Tabourin (Ka photographe), Didier Baussy (Le photographe)

Robert Bresson is today so widely acclaimed as one of the patron saints of cinema, it’s odd to think that in 1983 at Cannes he was furiously booed when he won the director prize for L’Argent. But Bresson’s style had always been divisive – before the vindication of history – and L’Argent, his final picture, is one of the purest, most uncompromising slices of Bressonism you are likely to see, not to mention an uncomfortable and deeply challenging work of art. Uncompromising in almost every sense, it is a film that climbs under your skin and troubles your mind for days after watching.

Based on a short story by Leo Tolstoy, L’Argent’s theme is the corrupting influence of money. Two rich kids, troubled by the small allowance from their parents, forge a 500 Franc note and exchange it for change in a photography shop. The owner, keen to get rid of the offending note, instructs his assistant Lucien (Vincent Ricterucci) to pay working-class Yvon Tonge (Christian Patey) with it. When Yvon uses it in a café, he is arrested and charged, his pleas of innocence ignored. Losing his job, with a wife and child to support, Yvon slides down a slippery slope encompassing theft, jail time, tragic bereavement and murder leaving him a brutal shell of the man he was before.

Bresson’s film deals with the inexorable inevitability of fate, once it is prodded in a certain direction by the destructive forces that govern our world. Those forces are themselves governed by cold, hard mammon and the selfishness and casual cruelty of those who have it or want it. Bresson’s film is littered with shots of hands at work – nearly always that work involves the passing of bank notes from one place to another. Money is what makes the world go around – it dictates power and privilege and it fundamentally decides who is believed and who is punished.

Yvon can plead in vain he is innocent of passing fake notes, because no one is going to listen to a working class joe with scarcely a penny to his name rather than the vouched-for employee of a respectable middle-class businessman. Yvon even ends his first court case by being rebuked for bringing into disrepute the names of such thoroughly respectable people. By contrast, when concerned her son might get caught up in the whole filthy affair, the mother of one of the original forgers simply hands over a wedge of cash to the cheated shop-owner to make the problem go away. Money talks.

And it has cast its verdict on Yvon, deciding he should be chewed up by the system and spat out a very different man. From the moment we first see Yvon arrested for the false note, we know he is doomed. Just as we know, from seeing Yvon’s first reaction to being accused (a violent shove that sends a waiter tumbling and glass smashing on the ground) that there is a capacity for violent revenge in him. Later, like a dim echo of this first moment, glass will shatter again on another floor, dropped by a grey-haired old woman hiding the fugitive Yvon. It’s a salutary reminder (one the film delivers on, with chilling impact, a few minutes later) that Yvon has a darkness that can harm others.

It’s a hardness sharpened by time in prison. Returning to the fertile ground of A Man Escaped, Bresson offers a chilling indictment of the prison system. Formal, cold and uncaring, it is a breeding ground for resentment and rage. The authorities read all incoming mail, but in no way think about its contents and the impact it will have on the receiver (the mail reading room is a voyeur’s paradise, the chance to observe the secret goings on of everyone before they even know it themselves). Incoming mail discovers Yvon’s sick daughter has died and his wife is leaving him for good. No attempt is made to support Yvon who quickly succumbs to rage (looking to strike a mocking fellow inmate with a metal serving spoon), punishment by isolation and a suicide attempt through stockpiling chill-pills (much easier to shut inmates up rather than help them).

Throughout Bresson shows the onslaught of cruel events on Yvon with his characteristic spare style (no music, well drilled actors, perfectly timed shots, composed to convey information in the most economical style possible). But L’Argent is also a film strikingly devoid of moral judgement. It’s very much left open to us when, how and why we may or may not lose sympathy with Yvon. After all we truly see him suffer, after trying his very best to play by all the rules (reporting where he got the fake note from, telling the truth in court) only for him to lose everything.

Is there a chance for redemption for Yvon? He discovers money talks and the world is fundamentally uncaring (after all it took his freedom, child, wife and a large part of his mental health). Photography shop assistant Lucien reaches the same conclusion: he’s been fleecing his crooked boss for weeks (‘I thought crooks looked after each other’ he tells his boss) but decides on one last theft to redistribute the wealth to the needy. Same conclusions, different methods to punish the world.

Yvon however decides to no longer restrain the dark impulses within him. He murders senselessly twice, grabs a few notes from a hotel cash desk and then finds himself protected be a selfless older woman (who he encounters initially eyeing up for theft). Staying in her home, her family in the same house, what will he do with this woman who does good things and expects nothing in return?

L’Argent is far from an optimistic film, with a hard-working family man turned into a family-free convict. In this uncompromising film, the final sequence is almost unwatchable in its bleak, terrible power as Yvon commits his final, inevitable, sins with a passion-free fixity of purpose almost impossibly horrible to watch. Bresson’s perfectly constructed film, full of detailed, clockwork precision has been slowly building to this horrific end, a natural one for a film highlighting the uncaring cruelty of the modern world.

Because money also doesn’t care about the damage it leaves, the collateral deaths or the cost on those on the margins. Was it this hopeless, systemic, inevitability the viewers at Cannes found so worthy of boos? The progress of events, one connected to another (and L’Argent, despite its structured formalism, is full of events of the least-Bressonist you can imagine, including a car chase) that forms a terrible, unsettling and unreassuring picture? Bresson leaves our judgement of Yvon entirely up to us: Tolstoy’s novella looked at the journey of redemption for its lead character. Bresson shows us the crimes and nothing else. If there is to be redemption or forgiveness we must ask ourselves if we can do it.