Would-be satirical mafia farce, that is slow, dense and insufficiently funny to hit its target

Director: John Huston

Cast: Jack Nicholson (Charley Partanna), Kathleen Turner (Irene Walkervisks/Irene Walker/Mrs Heller), Anjelica Huston (Maerose Prizzi), Robert Loggia (Eduardo Prizzi), John Randolph (Angelo Partanna), Lee Richardson (Dominic Prizzi), Michael Lombard (Rosario Filangi), Lawrence Tierney (Lt Davey Hanley)

Charley Partanna (Jack Nicholson) is a good-natured guy, loyal to his job – which just happens to be rubbing people out for the Prizzi crime family in New York. His gentle amble through Mafia life is thrown out of whack after a parade of unlucky events, silly mistakes and random occurrences. All of these can be linked back to his falling in love with Irene Walkervisks (Kathleen Turner), a con-woman, assassin and practised liar who may-or-may-not be in love with the besotted Charley. These two find themselves in the middle of a complex Prizzi family feud, much of it built up by Charley’s former girlfriend Maerose Prizzi (Anjelica Huston). What sides will everyone pick?

John Huston’s Prizzi’s Honor was one of the first films to take Mafia tropes, all that iconography The Godfather had made so ubiquitous and try and satirise it. Adapted from Richard Condon’s novel (by Condon), it carefully recreates the style and features of Mafia films, replaying the conventions – feuds, hits, femme fatales, pay-offs – with a streak of comedy. But what it lacks is the zip and energy this sort of dark satire really needs. It’s far too stately and never quite funny enough. Instead, it’s often slow and difficult to follow – and, damningly, is most engaging when it’s most like a regular gangster film.

It feels like an old man’s film. I’d defy you to look at this and then The Asphalt Jungle and not feel Huston was lacking fire here with this frequently untense, and slow film. It opens with a hugely over-extended wedding sequence, almost twenty minutes long, which laboriously introduces the characters. It frequently fails to pick to the pace from there: too many scenes lack thrust and drive, working their way slowly towards narratively unclear purposes. Now sometimes that is because so many of the characters are lying to each other – but Prizzi’s Honor does a consistently poor job of making sure we are either aware of the real truth or that we are in full understanding of the stakes at play.

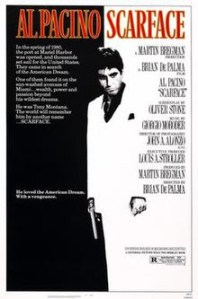

A large part of the fault is the wordy, dense screenplay from Richard Condon (how did a sharp adapter of books like Huston allow this?). It takes nearly an hour for the film to really get going with a proto gang-war initiated by Irene impulsively shooting a police captain’s wife during a botched hit. Along the way, it creates too many long conversation scenes that lack spark or wit. It’s a far too faithful an adaptation, relying far too much on telling not showing. Multiple off-screen plot developments (involving complex double cross schemes) are related to us through conversations that are (honestly) hard to follow, boring to watch and delivered and shot with a flat, functional lack of interest. All of these would have worked better with a mixture of words and visuals – seeing some of these complex events playout, with an accompanying voiceover (the sort of thing Scorsese would have done brilliantly – see Casino).

Neither script nor direction is sprightly or engaging enough. It’s languid musical score and the ambling camerawork and editing also doesn’t help. It consistently feels slow, it’s meaning fuzzy, it’s action not gripping enough, it’s jokes not funny enough. Each scene is either too over-stuffed with plot-heavy information or too light on emotional connection or purpose. I’d be surprised if many people could explain exactly how the plot mechanics worked when the credits roll which, for a film that gives over a lot of time to slowly explaining things in dense dialogue is not a good sign.

The film depends on its performers to spring into life. Best of all is Anjelica Huston’s Oscar-winning turn as Maerose, disgraced black sheep of the Prizzi family. She rips into this vampish manipulator, running rings around the other characters with her sexual power or superb play-acting (there is a great scene when she makes herself up to look depressed and miserable to win the sympathy of her dim kingpin father played by Lee Richardson). It’s a funny, engaging and dangerous performance that you wish was in the film a hell of a lot more than it is. Close behind is William Hickey, rasping with malice, as a lizardry Godfather full of greed, ambition and utterly lacking in morals, presenting a neat sideways parody of Brando-style figures.

The two leads have their moments. Jack Nicholson is surprisingly restrained as Charley, surely one of the most gentle and dim characters he’s ever played (probably the film’s best joke, since it’s JACK). Nicholson gives him a childish naivety, easy to manipulate, whether that’s Irene saying she definitely didn’t know about the Prizzi-robbing scam her late husband pulled alongside her or the rings the smarter Prizzi’s and his consiglieri father (a coldly jovial John Randolph) run round him. He’s sexually naïve – putty in the hands of Maerose (‘With the lights on?’ he asks with meek bewilderment when she invites him to a clinch in her apartment) and Irene (‘On the phone? Now?’ he asks when she suggests some sexy banter) – and, with his New Yoick accent and prominent upper lip feels like a dutiful child trusted to run errands by his parents.

Opposite him Kathleen Turner embraces the lusty femme fatale qualities that made her a star, playing a husky voiced practised liar with a ruthless heart. Prizzi’s Honor though deals Turner a tough-hand: she’s the most enigmatic character and possibly its most poorly developed, the film giving so little clarity to her inner life that part of me wonders if Turner herself was slightly confused as to her character. Even in a film where the female lead is a ruthless, murdering grifter, she’s still largely only seen in relation to the men in the film – a potentially satirical point the film doesn’t really develop at all.

Both actors give sterling performances, but so slow and artificial is the film, so laboured its pacing that I found it extremely hard to care about what was truth what was a lie. Prizzi’s Honor has small moments but it’s devoid of the energy and pace that could have made it a dark comic delight. With the lack of investment it creates in an audience, it’s frequently hard-to-follow plot developments and clumsy, unengaging exposition, even the dark ending is unlikely to make much an impact. Hugely praised at the time – partly, you feel, due to affection for its director – it’s a slow, unengaging film that only briefly sparks to life.