Decent performances from the leads can’t save a shamelessly manipulative, saccharine movie

Director: Penny Marshall

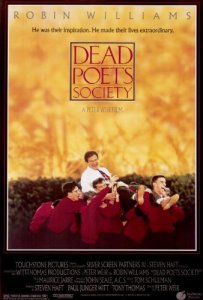

Cast: Robert De Niro (Leonard Lowe), Robin Williams (Dr Malcolm Sayer), Julie Kavner (Eleanor Costello), John Heard (Dr Kaufman), Penelope Ann Miller (Paula), Max von Sydow (Dr Peter Ingham), Ruth Nelson (Mrs Lowe), Alice Drummond (Lucy), Judith Malina (Rose), George Martin (Frank), Dexter Gordon (Rolando), Keith Diamond (Anthony), Anna Meare (Miriam), Mary Alice (Margaret)

There can be few things more terrifying than being trapped inside your own body, unable to engage with the world, but to be in a sort of waking coma for years. Imagine how wonderful – and how terrible – it might be if you briefly woke to normality, only to return to your catatonic shell? This actually happened to patients of Dr Oliver Sacks – here re-imagined as Dr Malcolm Sayer (Robin Williams) – in a Bronx hospital in 1969. Looking after catatonic survivors of the encephalitis lethargica epidemic of 1919-30, Sayer discovered they responded to certain stimuli: their name, music, catching balls etc. With an experimental drug he discovers he can restore the patients to ‘life’ – foremost among them Leonard Lowe (Robert De Niro), just a boy when afflicted – only to discover the effects won’t last and they are doomed to return to their coma-like state.

It’s such a terrible thing to think about that it even gives genuine emotional force to Awakenings an otherwise hopelessly manipulative, sentimental film that plays like a TV-Movie weepie. It certainly didn’t need the naked emotional manipulation that washes over the whole thing like a wave, with Randy Newman’s sentimental, tear-jerking score swells with every single heart-string tucking moment. Awakenings is so determined to make you feel every single moment it eventually starts to make the story less affecting than it really is. A simpler, less strenuous film would have been more moving rather than this film almost genetically engineered into ‘life-affirming’.

Everything in Awakenings feels like it is always trying too hard. Every moment is laid on for maximum emotional impact. Adapted from Oliver Sacks’ book chronicling individual cases, it presents a stereotypical Hollywood ‘feelings’ film, with lessons for all. Worse, there is a tedious ‘seize the day’ message that keeps ringing out of the film. The awakening is, of course, not only literal but metaphorical – the patients (and their doctors) ‘awoke’ to appreciate life and living more. It’s hard not to think at times there is something rather patronising about partially using Leonard’s brief experience as a lesson for Dr Sayer to stop being so damn timid and ask a nurse out on a date. As traumatic as it is for Leonard to return to his coma, at least Dr Sayer learned to live a little!

It’s a very fake attempt at a hopeful ending to an otherwise down beat true-story. Dr Sayer is a retro-fitted version of Oliver Sacks, sharing many of his characteristics – but not his sexuality or decades long celibacy – and the film presents him, as Hollywood loves to with geniuses, as a shy, awkward type who no-one of course could expect anything of. He combines this with quiet maverick tendencies, putting the patients first against the ‘numbers-first-risk-free’ obstructionist bureaucrats (represented, of course, by John Heard, though he does thaw a little) who run the hospital and poo-poo his ideas.

Awakenings is full of sickly moments of heavy-handed sentimentality – its opening shot of Leonard as a boy carving his name in a bench under the Brooklyn Bridge tells you immediately one of the first places he’ll go as an adult for a wistful smile – that keep trying to do the work for you. (Of course, all the nurses and cleaning staff offer up cheques to help pay for the patients drugs!) The story doesn’t need it. Just seeing the facts of these vibrant adults emerge for a brief time in the sun is moving enough. Leonard quietly, but with dignity, asking the hospital board for permission to go outside alone is more moving than watching him forcibly dragged from the door by porters or seeing him rant on the mental ward he’s been consigned to as a punishment. We don’t need Sayer to literally tell us some things are too sad for him to film, when we can see it on Williams’ face.

The leads are not always immune to the try hard nature of the film, but they do some decent work. De Niro (Oscar-nominated) brings a touching sweetness to Leonard, essentially a boy who wakes in the body of an adult. There is a genuine wonder in his eyes at the world around him – wonder that transforms into frustration at the continued restrictions placed on his freedom. There is something slightly studied about the physical effects (especially in the film’s final act) but De Niro understands that underplaying and quiet honesty is more moving than when the film pushes him towards grandstanding.

Williams is also very good – if at times a little mannered – as the quiet, awkward Sayer. With the less flashy – but potentially more complex role – he again shows how close humour is to pathos. It’s a performance with several little eccentric comic touches, but wrapped up in a humanitarian shell of earnestness that is quite affecting. It’s a shame that the film constantly undermines his restraint by using every conceivable trick of framing, scoring and composition to wring sentiment from him.

But then that’s Awakenings all over. You can imagine the script covered with annotations along the lines of ‘make them cry here’. And it worked with a great many people, the mechanical nature of the film working overtime to tickle the tear ducts. But the film’s utterly unnatural sense of artifice constantly prevents you from really feeling it. You are always aware of Marshall nudging you to remind you of the unbearable emotion and the tragedy of lives not lived. All easily washed down in a narrative structure as old as the hills – Sayer is an outsider who proves himself, he and Leonard fall out then come back together stronger than ever etc. etc. – that continually reminds you of its functional, manipulative nature.