Smash-hit romance that I found forced, smug, tiresome and very mediocre

Director: Arthur Hillier

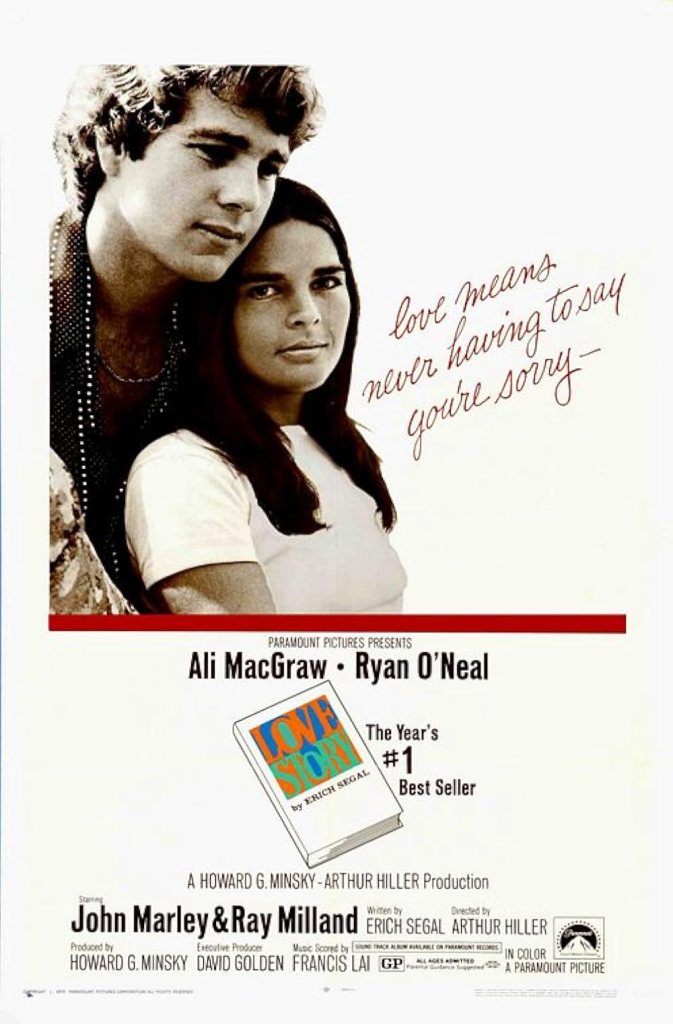

Cast: Ali MacGraw (Jenny Cavilleri), Ryan O’Neal (Oliver Barrett IV), John Marley (Phil Cavilleri), Ray Milland (Oliver Barrett III), Russell Nype (Dean Thompson), Katharine Balfour (Mrs Barrett), Sydney Walker (Dr Shapeley), Tommy Lee Jones (Hank Simpson)

Right from the top Love Story tells you it ain’t Happy Story, as grieving Oliver Barrett (Ryan O’Neal) wistfully asks in voiceover what you can say about a 25-year-old girl who died. The girl, we quickly work out, is Jenny Cavilleri (Ali MacGraw) and the fact we all know she’s doomed didn’t stop Love Story turning into a mega-hit. But a mega-hit isn’t a good film: and Love Story, to tell the truth, is not a good film. And, in the spirit of its mantra “Love means never having to say you’re sorry” I’m not apologising for that (it also sounds like the sort t-shirt friendly message you might see an abusive spouse wearing).

Oliver comes from a wealthy background, with expectations from his father (Ray Milland) that he will follow in the Barrett family footsteps, to study in Barrett Hall at Harvard and join the Supreme Court. Jenny is the daughter of a baker (John Marley) who dreams of becoming a musician. They meet at college, fall in love and want to marry. Oliver’s father asks his son to wait, Oliver says no, is cut off and he and Jenny work to put him through Harvard (to inevitable success). He gets a high-powered job, she gets a terminal illness. Let the tissues come out.

Anyway, Love Story charts the star-crossed romance between O’Neal and MacGraw, defining their careers and melting the hearts of millions. But to my eyes, this dull, distant, dreary romance lacks charm. The dialogue strains to try and capture a Hepburn-Tracy sparky banter, but it’s as if writer Erich Segal has heard about what a screwball comedy is without ever having actually seen one. O’Neal calling MacGraw a bitch within 180 seconds of the film starting doesn’t feel like a spiky banter, but just plain creepy. All the way through the film’s sentimental courtship, the dialogue consistently makes its characters sound sulky, whiny and self-involved.

This isn’t helped by the fact that both actors lack the charisma and energy these sorts of parts need. Both end up sounding infuriatingly smug and their leaden dialogue clunks out of their mouths, stubbornly refusing to come to life. When the emotion kicks in, neither can go much further than wistful stares with the hint of a tear, which isn’t much of a difference from their forced laughter and studied embraces. Put bluntly, both O’Neal and MacGraw do little to breathe life into the Romeo and Juliet construct the film totally depends on. Watching it with my older, cynical eyes… I quickly lost patience with this pair. I also find it hilarious that O’Neal himself married age 21, divorced by 23 and essentially said the whole thing was a youthful mistake.

Is it really that unreasonable for his father to suggest that perhaps Oliver shouldn’t rush into marriage with a girl he has literally just met? It wouldn’t take much reangling to see Oliver as a Willoughby-type, leading on a love-struck young woman in a selfish act of rebellion. Certainly, I can’t help but see Oliver as (to a certain extent) a stroppy, entitled rich-kid rebelling against his Dad. Just as I can’t help but feel, when he aggressively tells Jenny to mind her own business when she broaches a reconciliation, that he’s more than a bit of a prick. But then, the film keeps vindicating him, by implying his Dad must be an arsehole because he’s rich and reminding us that of course love means never saying you’re sorry.

As for Oliver’s whining about his money problems, being forced (can you believe this!) to actually work to make his way in life – give me strength. Clearly, we are meant to side with him when he is incredulous that Harvard’s Dean refuses to grant him a scholarship (on the grounds they are for academically gifted poor kids, not scions of the Founding Fathers with Daddy Issues). But Holy Smokes, Oliver reacts like a brat who no-one has never said no to before. He even has the gall to complain that he is the real victim of the economic status quo. Every time he bangs on about the difficulties of paying for Harvard (even after Jenny dutifully abandons her dreams to help pay for him), I literally shouted at the screen “sell your car you PRICK” (how many coins would this high performance, expensive to run, classic car get him?). The film never really tackles Oliver’s sulky lack of maturity (he can’t even get through an ice hockey match without throwing a hissy fit), not helped by O’Neal even managing to make grief feel like sulking.

To be honest Jenny isn’t much better. This is a ‘character’ where quirk takes the place of personality. From her forced nick-name of “Preppy” for Oliver (better I suppose than his early nick-names for her, most of which use the word bitch), to her pretentiously shallow love of classical music (she knows all the classics and that’s about it). Her whimsical insistence about calling her dad ‘Phil’ because she’s such a free spirit. MacGraw’s limitations as an actress and flat delivery of the dire-logue accentuate all these problems, preventing Jenny from ever feeling anything other than a rich-kid’s wet-dream of what a boho pixie-dream girl from the sticks might be like.

You can probably tell that the film got my back up so much, I felt like giving up on love. Everything in the film is smacking you round the head to make you feel the feelings. Its vision of New York is a snow-soaked Narnia where it’s always Christmas. The Oscar-winning song soaks into the syrupy soundtrack. I suppose it’s interesting to be reminded of an era where the husband is told about his wife’s fatal illness before she is (and warned not to tell her). But so much else about Love Story had me reaching for a paper bag.

Surprisingly distant, dull, led by two unengaging actors speaking terminally flat dialogue, it was nominated for seven Oscars and made millions. But the longer this Love Story hangs around, the less interesting it seems. A love story that feels like it will only move those who have never seen a love story before.